Du Bois’ Data Portraits Tell A Story About Black Life In Georgia And Beyond

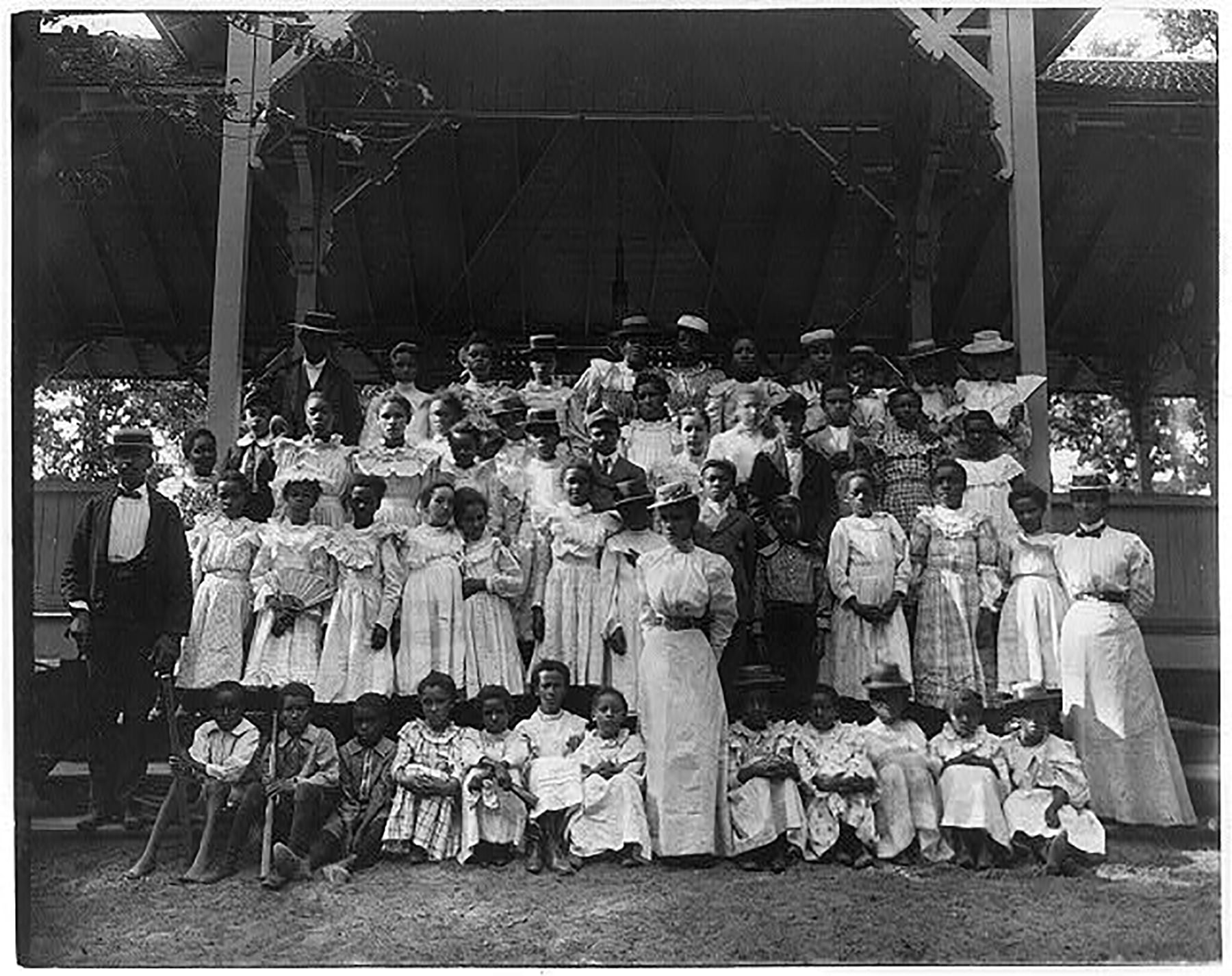

This image, taken in either 1899 or 1900, shows African-American children with a few adults in a pavilion. It was part of the “American Negro” exhibit curated by W. E. B. Du Bois for the 1900 Paris World Fair.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

When W.E.B. Du Bois wrote about the color line in “The Souls of Black Folk,” he lamented the racism that disenfranchised and discriminated against African-Americans in the 20th century. The split between blacks and whites that the color line represents is most often interpreted through Du Bois’ writing, but the famed sociologist and civil rights activist also put a visual to it.

In 1900, Du Bois led a team of students and alumni from Atlanta University (now Clark Atlanta University) in designing a set of data portraits for the Exposition Universelle, a world’s fair in Paris. The fair was a global stage on which nations could exhibit and celebrate their pride and achievements.

“The dominant narrative at these expositions in terms of nonwhite peoples was … the representation of people as savages, as people who needed to be uplifted by colonialism, by imperialism,” said Britt Rusert, professor of Afro-American studies at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. “So it was really crucial that people of color had something to say within these spaces.”

For the exposition, Du Bois curated the “American Negro” exhibit, which included artifacts, texts and images aimed at refuting these imperialist ideas by showing everyday African-American life and progress.

Among the images were 63 hand-drawn data portraits designed and created by Du Bois and his team. Rusert and fellow UMass Amherst professor Whitney Battle-Baptiste, who is also the director of the W.E.B. Du Bois Center at the university, have co-edited a book compiling the portraits titled “W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America.”

Using neat, meticulous lines, bright colors and interesting shapes, the portraits detail everything from the occupations and conjugal conditions of African-Americans in Georgia to the income and expenditure of black families in Atlanta.

“It was not just one aspect of African-American life in the U.S. It wasn’t about slavery — it was about progress post-slavery,” said Battle-Baptiste.

The portraits were coupled with images of African-Americans in the rural South who were entrepreneurs, homeowners and students at historically black colleges and universities — things she says African-Americans often weren’t associated with at that time.

The images are a deviation from the dark, shadowy tone of Du Bois’ writing.

In “The Souls of Black Folk,” he describes African-Americans as existing under a “veil” that prevented whites from seeing them as human beings and being bound by the double consciousness – constantly viewing themselves through the lens of a racist, white society.

“It was not just one aspect of African-American life in the U.S. It wasn’t about slavery — it was about progress post-slavery.”

Whitney Battle-Baptiste, co-editor, W.E.B. Du Bois’s Data Portraits: Visualizing Black America

But the data portraits tell a different story – the vibrant images show movement and life, with the lines forming a series of spirals, circles, rectangles and other abstract shapes.

“[These images seem] to suggest that there’s a way out of the bind of double consciousness, or that there is a future beyond Jim Crow in a way in which when you read ‘The Souls of Black Folk,’ and if you read other accounts of how Du Bois is thinking about the kind of problem of race relations in this moment, it’s a little bit harder to imagine a way out of that system,” Rusert said. “We don’t see those shadows in these images … it’s a very different aesthetic of the color line.”

Rusert adds the design of the data portraits expresses modernity and industrialization, a nod to black futurity, especially in the South – Atlanta, specifically, which at the time was becoming the hub of African-American culture that it is today. She and Battle-Baptiste say they would love to see how Du Bois might have used the portraits more than a century later – or how others might use them.

“This is very much the 1900 version of Data for Black Lives,” Rusert said, referring to a modern-day movement of activists, organizers and mathematicians advocating for the use of data and statistics to advance social justice. “The kind of use of data that’s about black life rather than black death, and that’s really what Du Bois and his group are doing.”

Battle-Baptiste echoed that.

“Whether it’s 1900 or whether it’s 2019 … people can see this information and use it in a way that Du Bois wished, I think, he could have, but never had the opportunity to,” said Battle-Baptiste. “Stories help to connect people, and I hope in some ways, data allows for black lives to be a part of that conversation.”