Ryan Gravel’s Next Big Idea: Eat, Drink, Save The World

Ryan Gravel stands in front of a window that will be the backdrop to the bar at his planned restaurant Aftercar. It’s immediately parallel to the BeltLine’s Eastside Trail.

Jim Burress / WABE

Ryan Gravel.

If you don’t immediately recognize the name, chances are you know his vision. The mastermind behind Atlanta’s BeltLine hopes you won’t stop there, though.

Gravel is almost evangelical in his belief that common, everyday folks have the answers to Atlanta’s — or any other city’s — big-picture challenges. Sometimes, we just need a catalyst. And Gravel is betting his latest venture will be just that.

You’d be forgiven for not hearing the excitement in Gravel’s voice as he shows off the street-level space along the BeltLine’s Eastside Trail. As stoic as he seems when presenting the property that will house both his nonprofit and the restaurant whose proceeds will fund it, the excitement is there.

“The factory made telephones,” Gravel says, entering a sweeping, expansive room.

The space shows both the wear of its years and the early promises of its renewal; overhead, a distinct paint line abruptly ends, showing where a drop ceiling undoubtedly used to make the space seem more intimate, and the bare concrete left behind looks almost too authentic.

“This is the cafeteria for the old factory,” he says, his voice bouncing off the now empty walls of the art deco building’s first floor. Workers once ate lunch here before finishing their day assembling telephones and switchboards for the Western Electric Co.

More recently, the space in the Poncey-Highland neighborhood has played silent witness to dads jogging by, strollers and dogs in tow, as well as strings of millennials complaining about Atlanta’s suddenly unaffordable supply of cookie-cutter apartments.

“So you see the terrazzo floor — this cool arched ceiling,” Gravel says pointing first downward then way up to the curve above his head. The echo radiating off the ceiling makes the place feel like a very well-lit subway tunnel.

“This was the space where people dined,” he says. “And this will be the restaurant dining hall.”

The fact Gravel has never operated a restaurant doesn’t seem to faze him — it’s a minor detail, and letting details stand in his way is not a part of his brand.

Take the BeltLine. The 22-mile loop was Gravel’s idea when he was a grad student at Georgia Tech in the ’90s. It’s built on Atlanta’s historic rail corridors and already has spurred more than $4 billion in development.

Early on, where few saw promise, Gravel saw a bridge. The improbability of making the idea kinetic didn’t matter.

“The public fell in love with this vision that was better than what they saw through their car windshields,” Gravel says. “They empowered and ultimately obligated their elected officials to do it.”

It was expensive. They didn’t own the land. The political climate at the time was “hostile” to public transportation, Gravel says.

“And we changed all that,” he says.

The BeltLine is changing Atlanta. But it’s only one solution to an ever-growing list of problems the city faces. The answers to those problems, Gravel says, won’t come from executives or elected officials sitting around a boardroom table. It’ll come from a dinner table.

“The best social and cultural movements in world history came out of bars and restaurants,” Gravel says. He cites Atlanta’s own Paschal’s Restaurant, hailed as the dining room of the civil rights movement.

“People came together, saw themselves [with] a shared future, organized, and they literally changed the world,” he says.

There’s something innately human about the act of sharing food and drink, Gravel says — it brings people together. That’s what the urban planner hopes will happen in this space, a concept he describes as a “retro-future BeltLine social house.”

He’ll call it Aftercar.

Don’t read too much into the name. Beyond the fact it’s a made-up word, the concept it represents has less to do with automobiles and more to do with the unseen challenges we as a society will face when we rely on, say, autonomous vehicles.

“Automation, I think, is going to solve a lot of problems,” Gravel explains. “It’s also going to create a lot of other new problems. And I think that’s something that a lot of people don’t really talk about, especially in the context of [issues] like gentrification, social equity,” and technology broadly defined, he says. There will be new winners and losers, Gravel points out. “And if we’re not talking about those things then we’re not going to be prepared.”

If all that comes across as highbrow and lofty, Gravel gets why. He’s heard it all before.

“A lot of people have asked why we’re doing this, and this location,” he says, prefacing his response with an admission that the venture, for him, is personal. Gravel wants to counter a narrative he hears over and over about the BeltLine — that it’s only for white hipster yoga practitioners who are more than willing to overpay for a craft beer.

“I like the idea of not conforming necessarily to that narrative,” Gravel says, adding that Aftercar will be a place “where everybody feels like they can come to and are invited.” A real-life, Atlanta-fied Cheers, where names don’t matter but ideas do.

Cost shouldn’t be a barrier, Gravel says, which is why Aftercar’s still-to-be-determined menu will feature eats on the cheap.

But not too cheap.

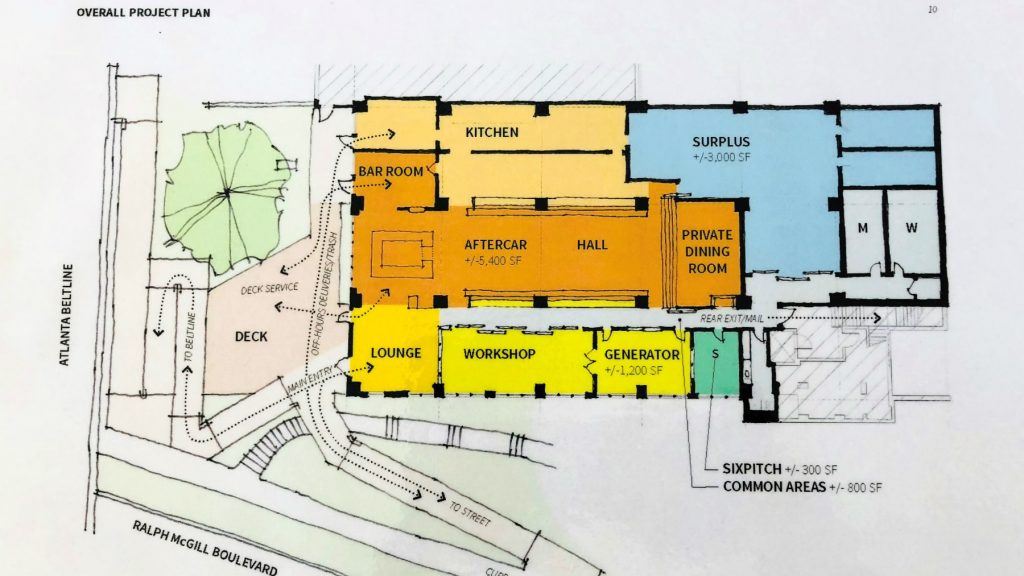

After all, the venue needs to make money — has to make money. He’s counting on Aftercar’s profits from food served to people engaged in world-changing conversations to fund his other venture. It’s called Generator, a nonprofit housed in the same space that he describes as a “future of our lives-oriented idea studio.”

Big ideas take big funding. And the million-dollar price tag to get Aftercar off the ground could be the one thing that visibly worries Gravel. He says he’s halfway home in terms of making Aftercar a turnkey operation.

“The response to this idea and really the need for this kind of dialogue in this kind of a space has been really unbelievable,” Gravel says. “I’m optimistic that we’re going to get to that number in the next couple months. That’s our goal.”

If Ryan Gravel’s next big idea has just a fraction of the buy-in of his last big idea, he’ll have no problem meeting the self-imposed deadline for Aftercar’s grand opening, penciled on the calendar for mid-2019.