That phrasing and an understanding of cadence were all important to the success of these speeches, according to Carolyn Calloway-Thomas, director of graduate studies at the Department of African American and African Diaspora Studies at Indiana University.

King’s training in the pulpit gave him a strong insight into what moves an audience, she says. “Preachers are performers. They know when to pause. How long to pause. And with what effect. And he certainly was a great user of dramatic pauses.”

Here are four of King’s speeches that sometimes get overlooked, plus the one he delivered the day before his 1968 assassination. Collectively, they represent historical signposts on the road to civil rights.

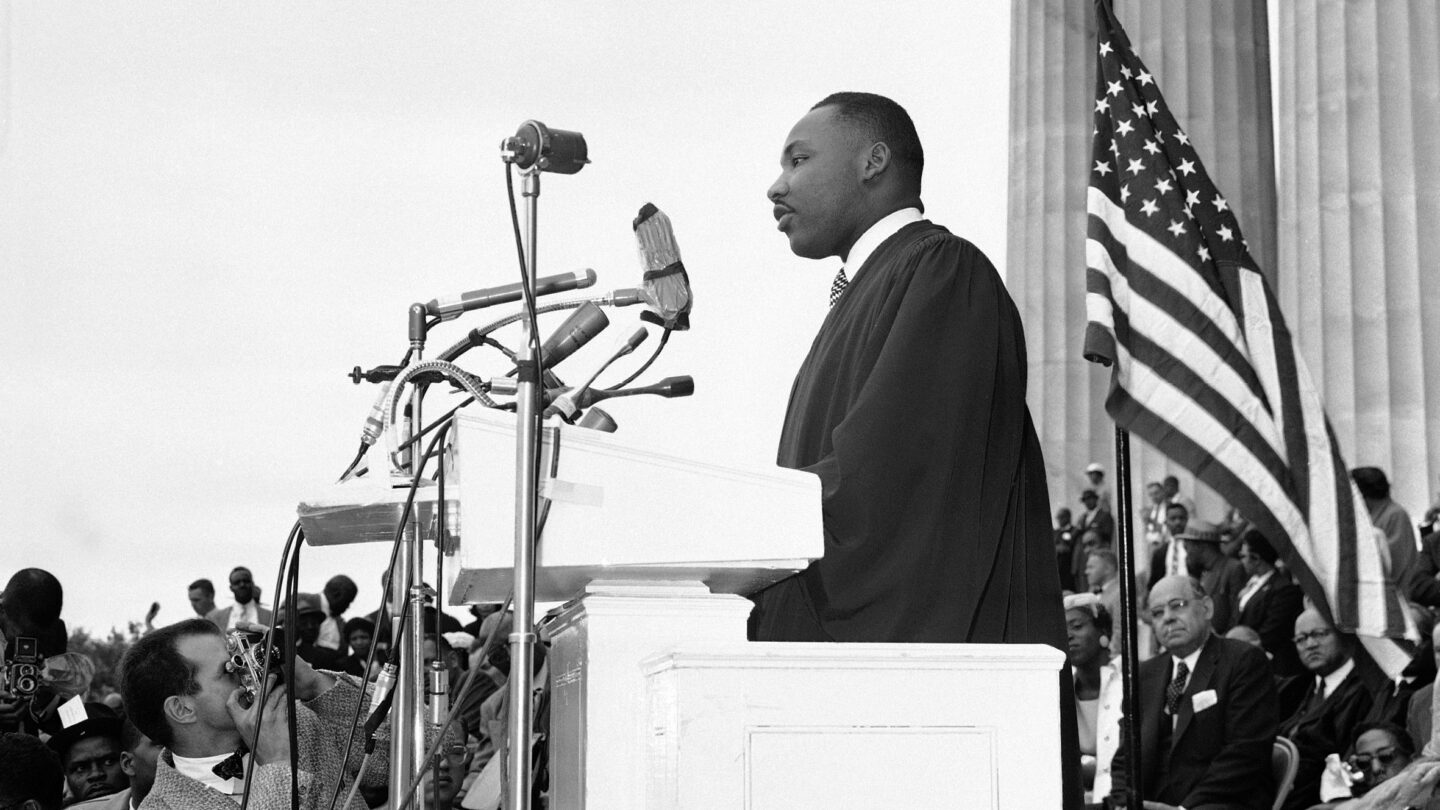

King spoke at the Lincoln Memorial three years to the day after the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which struck down the “separate but equal” doctrine that had allowed segregation in public schools.

But Jim Crow persisted throughout much of the South. The yearlong Montgomery bus boycott, sparked by the arrest of Rosa Parks, had ended only months before King’s speech. And the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which sought to end disenfranchisement of Black voters, was still eight years away.

“It’s a very important speech because he’s talking about the importance of voting and he’s responding to some of the Southern resistance to the Brown decision,” says Vicki Crawford, director of the Martin Luther King Jr. Collection at Morehouse College, King’s alma mater.

The speech calls out both major political parties for betraying “the cause of justice” and failing to do enough to ensure civil rights for Blacks. He accuses Democrats of “capitulating to the prejudices and undemocratic practices of the Southern Dixiecrats,” referring to the party’s pro-segregation wing. The Republicans, King said, had instead capitulated “to the blatant hypocrisy of right-wing, reactionary Northerners.”

He also indicts Northern liberals who are “so bent on seeing all sides” that they are “neither hot nor cold, but lukewarm” in their commitment to civil rights.

“King [was] calling on both parties to take a look at themselves,” Crawford says.

With the movement gaining steam, King used his speech to take stock of where things stood and what must be done next, Calloway-Thomas says. “He is revisiting the status of African American people.”

The speech was delivered after the last of three Selma-Montgomery marches to call for voting rights. Protesters were beaten by Alabama law enforcement officials at the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma on March 7 in what came to be known as Bloody Sunday. Among the nearly 60 wounded that day by club-wielding police was John Lewis, the chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who suffered a fractured skull. (Lewis later served 17 terms in the U.S. House of Representatives.) A second attempt to reach Montgomery a few days later was again turned back at the bridge. In a third try, marchers finally reached the steps of the Alabama State Capitol on March 25.

“Finally the group of protesters gets all the way to the Capitol, and King delivers a speech to what we think is about 25,000 people,” Miller says. The speech is also often referred to as the “How Long? Not Long” speech because of that powerful refrain, Miller says.

Jonathan Eig, author of the biography “King: A Life,” published last year, says he thinks about three-fourths of the speech was written out. “Then [King] goes off script and gives a sermon.”

That’s when he answers the question “How long?” for his audience. How long will it be until Black people have the same rights as white people? “Not long, because no lie can live forever,” King tells his exuberant listeners.

“That’s the part that really echoes. No question,” Eig says. “And I think that’s when he knew he was at his best. He knew that he could bring the crowd to its feet and inspire them.”

Also notable is a famous anecdote that King shared in his speech, one that appeared earlier in his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” addressed to his “fellow clergymen.” It relates the words of Sister Pollard, a 70-year-old Black woman who had walked everywhere, refusing to ride the Montgomery buses during the 1955-1956 boycott.

“One day, she was asked while walking if she didn’t want to ride,” King said, speaking to the crowd that had just successfully marched from Selma to Montgomery. “And when she answered, ‘No,’ the person said, ‘Well, aren’t you tired?’ And with her ungrammatical profundity, she said, ‘My feets is tired, but my soul is rested.'”

“And in a real sense this afternoon, we can say that our feet are tired but our souls are rested,” he said.

The story of Sister Pollard would be used again in the coming years.

But the speech may be best remembered today for another line, where King said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice.”

In fact, King was using the words of a 19th-century Unitarian minister, Theodore Parker. Parker was an abolitionist who secretly funded John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry in 1859, often seen as an opening salvo of the Civil War. In a sermon given seven years before the raid, Parker used the line that King would pick up more than a century later.

“Dr. King absorbed all kinds of material, heard from others, used it on his own. But this is what we call appropriation or transformation when the old seems new,” Miller says.

“Beyond Vietnam” (April 4, 1967 — New York City)

King had already begun speaking out about the war in Vietnam, but this speech was his most forceful statement on the conflict to date. Black soldiers were dying in disproportionate numbers. King noted the irony that in Vietnam, “Negro and white boys” were killing and dying alongside each other “for a nation that has been unable to seat them together in the same schools.”

“So we watch them, in brutal solidarity, burning the huts of a poor village, but we realize that they would hardly live on the same block in Chicago,” he said. “I could not be silent in the face of such cruel manipulation of the poor.”

SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael, a major civil rights figure, had come out against the war and encouraged King to join him. But some in King’s own inner circle had cautioned him against speaking about Vietnam.

Although powerful and timely, the speech drew a harsh and immediate reaction from a nation that had only just begun to reckon with the rising casualties and economic toll of the war. Both The Washington Post and The New York Times published editorials criticizing it. The Post said King had “diminished his usefulness to his cause, his country, his people” and the Times said he had “dampened his prospects for becoming the Negro leader who might be able to get the nation ‘moving again’ on civil rights.”

King knew he would take heat for the speech, especially from the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson, with whom he’d worked to get the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, a year later, the Voting Rights Act, through Congress. With the presidential election just 19 months away, continued support of Johnson’s Vietnam policy was crucial to his reelection. Nearly 10 months after the speech, however, the Tet Offensive launched by the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese army would help turn U.S. public opinion against the war and lead Johnson to not seek another term.

But in April 1967, the reaction to the speech was “far worse than King or his advisers imagined,” says Miller, of North Carolina State University. Johnson “excommunicated” the civil rights leader, he says, adding that even leaders of the NAACP expressed disappointment that King had focused attention on the war.

“His immediate response was that he was crushed,” Miller says. “There are a number of people who have documented that he literally broke down in tears when he realized the kind of backlash towards it.”

He was criticized from both sides of the political aisle. Sen. Barry Goldwater, R-Ariz., a staunch conservative who made a failed run for the presidency in 1964, said King’s speech “could border a bit on treason.”

“King himself said that he anguished over doing the speech,” says Indiana University’s Calloway-Thomas.

The three evils King outlines in this speech are poverty, racism and militarism. Referring to Johnson’s Great Society program to help lift rural Americans out of poverty, King said that it had been “shipwrecked off the coast of Asia, on the dreadful peninsula of Vietnam” and that meanwhile, “the poor, Black and white are still perishing on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity.”

Calloway-Thomas calls it “the most scathing critique of American society by King that I have ever read.”

“We need, according to him, a radical redistribution of political and economic power,” she says, “Is that implying reparations? Is that implying socialism?”

Calloway-Thomas hears in King’s words an antecedent to the Black Lives Matter movement. “One sees in that speech some relationship between the rhetoric of Dr. King at that moment and the rhetoric of Black Lives Matter at this moment,” she says.

It was also one of the many instances where King quoted poet Langston Hughes, with whom he had become friends. “What happens to a dream deferred? It leads to bewildering frustration and corroding bitterness,” King said in a nod to Hughes’ most famous poem, “Harlem.”

King and Hughes traveled together to Nigeria in 1960, Miller notes, calling the poet an often unrecognized but nonetheless “central figure” in the early Civil Rights Movement. “They exchanged letters. Dr. King told [Hughes] how much he used his poetry. Dr. King used seven poems by Langston Hughes in his sermons and speeches from 1956 to 1958.”

This is King’s last speech, delivered a day before his assassination at the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968. He was in the city to lend his support and his voice to the city’s striking sanitation workers.

“He wasn’t expecting to give a speech that night,” according to Clayborne Carson, Martin Luther King, Jr. centennial professor emeritus at Stanford University. “He was hoping to get out of it. He was not feeling well.”

“They call him and say, ‘The people here want to hear you. They don’t want to hear us.’ And plus, the place was packed that night” despite a heavy downpour, Carson says. “I think he recognized that people really wanted to hear him. And despite the state of his health, he decided to go.”

The haunting words, in which King says, “I’ve seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you” have led many people to think he was prophesying his own death the following day at the hands of assassin James Earl Ray.

“The speech really does feel a bit like his own eulogy,” says Eig. “He’s talking about earthly salvation and heavenly salvation. And, in the end, boldly equating himself with Moses, who doesn’t live to see the Promised Land.”

The speech is largely, if not entirely, extemporaneous. And by the end, King was exhausted, says Carson. “It’s pretty clear when you watch the film that he’s not in the best shape.”

“He barely makes it to the end,” he says.

“But he relied on his audience to bring him along,” Carson says. “I think it’s one of those speeches where the crowd is inspiring him and he’s inspiring them. That’s what makes it work.”

It’s a great speech, made greater still because it was his last, says Calloway-Thomas.

“You have this wonderful man who epitomized the social and political situation in the United States in the 20th century,” she says. “There he is, dying so tragically and dreadfully. It has a lot of pity and pathos buried inside it.”

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))