With 150,000 Russian troops circling Ukraine’s borders and U.S. officials warning that a major invasion could take place any day, President Biden has signaled to the American public that it, too, may feel effects if Russia chooses to invade.

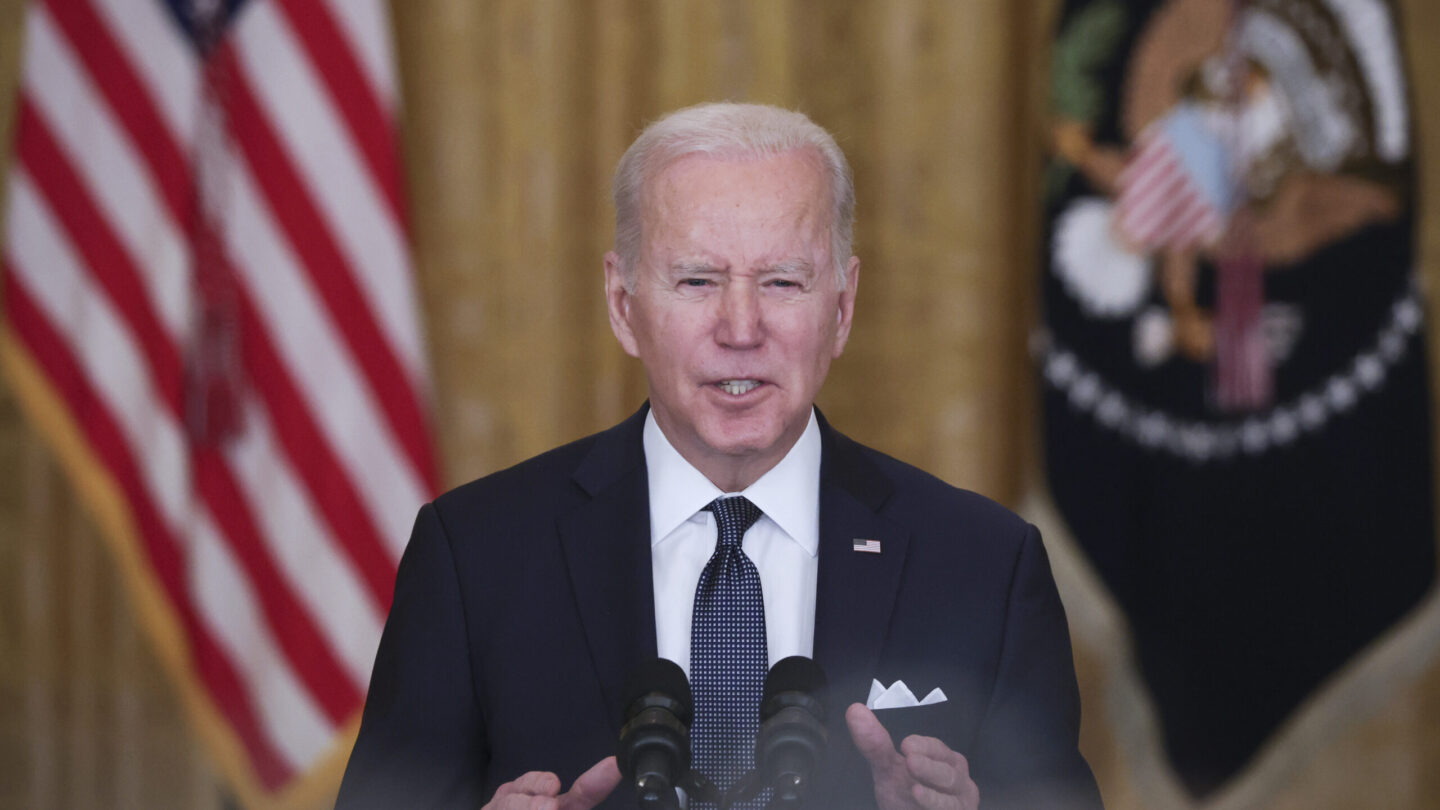

“If Russia decides to invade, that would also have consequences here at home. But the American people understand that defending democracy and liberty is never without cost,” President Biden said in a speech Tuesday. “I will not pretend this will be painless.”

Russia says it is not preparing to invade, and it is not a certainty that Russian President Vladimir Putin will decide to do so. World leaders are continuing diplomatic talks this week in a high-stakes effort to avoid that outcome.

Still, the possibility of an invasion has raised the specter of consequences — sanctions, counter-sanctions, energy supply issues, a flood of refugees — that would be felt far beyond Ukraine’s borders.

Here’s what to know.

The U.S. has promised severe sanctions if Russia invades — and Russia could retaliate

“If Russia proceeds, we will rally the world and oppose its aggression. The United States and our allies and partners around the world are ready to impose powerful sanctions and export controls,” Biden said Tuesday.

Those sanctions could include restrictions on major Russian banks that would dramatically affect Russia’s ability to conduct international business. Severe U.S. sanctions could drive up prices for everyday Russians or cause Russia’s currency or markets to crash.

Because the U.S. does not rely much on trade with Russia, it is somewhat insulated from direct consequences. Europe is more directly affected. But certain sectors of the U.S. economy rely on highly specific Russian exports, primarily raw commodities.

“The premise of sanctions is to hurt the other guy more than you hurt your own interests. But that does not mean there will not be some collateral damage,” said Doug Rediker, a partner at International Capital Strategies.

Energy prices could soar

Russia is a major exporter of oil and gas, especially to Europe. As a result, officials have reportedly shied away from severe sanctions on Russian energy exports.

But there are other ways the energy market could be disrupted.

For one, Russia could choose to cut off or limit oil and gas exports to Europe as retaliation for sanctions. Nearly 40% of the natural gas used by the European Union comes from Russia — and no European country imports more than Germany, a key U.S. ally.

Even if Russia chooses not to limit exports, supplies could still be affected by a conflict in Ukraine because multiple pipelines run through the country, carrying gas from Russia to Europe. “They could simply be casualties of a military invasion,” Rediker said.

Either way, if Europe’s natural gas supply is pinched, that could cause energy prices — which have already been climbing — to rise even further. And even though the U.S. imports relatively little oil from Russia, oil prices are set by the global market, meaning local prices could rise anyway. On Tuesday, Biden promised to work with Congress to address “the impact of prices at the pump.”

Other industries, from food to cars, might also be hurt

Russia is a major exporter of rare earth minerals and heavy metals — like titanium used in airplanes. Russia supplies about a third of the world’s palladium, a rare metal used in catalytic converters, and the price has soared in recent weeks over fears of a conflict.

And a major conflict in Ukraine would disrupt Ukrainian industries, too. Ukraine is a major source of neon, which is used in manufacturing semiconductors.

As a result, U.S. officials have warned various sectors to brace for supply chain disruptions, including the semiconductor and aerospace industries.

Fertilizer is produced in major quantities in both Ukraine and Russia. Disruptions to those exports would mostly affect agriculture in Europe, but food prices around the world could rise as a result.

The shock to international stability could hit global markets

Beyond sanctions and counter-sanctions, global financial markets would likely have a negative reaction to a European military invasion of a scale not seen since World War II.

Americans with exposure to the stock market — like those with 401(k)s and other retirement accounts — could feel an effect, though it most likely be short-term.

“Markets are fundamentally not prepared for a land war in Europe in the 21st century,” Rediker said. “It’s something people just have not contemplated.”

The U.S. stock market has already been unusually volatile in recent weeks, churning over inflation, possible moves by the Federal Reserve and the possible conflict in Ukraine.

Historically, the market has bounced back relatively quickly after geopolitical events. That’s what’s most likely today, too, analysts say.

But if a major Russian invasion and subsequent conflict cause long-lasting disruption of energy markets and other exports, investors could rethink that conventional wisdom.

“You’re potentially at a point where not only are we looking at Russia potentially invading Ukraine and sanctions and countermeasures, but you are also looking at a rise of China that doesn’t necessarily agree with the American perspective on the world anyway,” Rediker said. “Are we looking at a point in which some of the major premises that people take for granted have to be reassessed?”

Russia might respond with disruptive cyberattacks on U.S. targets

Another way Russia could respond to U.S. sanctions is through cyberattacks and influence campaigns.

Various federal agencies, including Treasury and Homeland Security, have warned of possible cyberattacks on targets like big banks and power grid operators. And just last week, U.S. cybersecurity officials held a tabletop exercise to ensure that federal agencies were prepared for possible Russian retaliation, The Washington Post reported.

“They have been warning everyone about Russia’s very specific tactics about the possibility of attacks on critical infrastructure,” Katerina Sedova, a researcher at Georgetown’s Center for Security and Emerging Technology, told NPR.

Russian cyberattacks have targeted Ukraine relentlessly in recent years, including attacks on Kyiv’s power grid in 2015 and 2016. But a major escalation could shift focus to U.S. targets.

Sedova pointed to the Russian state-backed attack on the IT software company SolarWinds and a ransomware attack that shut down the Colonial Pipeline for six days as examples of how major Russian cyberattacks could disrupt U.S. operations. (The Biden administration said it does “not believe the Russian government was involved” in the pipeline attack.)

Power grids, hospitals and local governments could all be targets, she said.

For now, Sedova said she is more worried about subtler attacks — like influence campaigns that aim to “sow discord between us and our allies in our resolve” to act jointly against Russia.

“Oftentimes, cyber operations go hand in hand with influence,” she said. “They’re targeting a change of decision-making, a change in policy in that direction, a change in public opinion.”

A major invasion would likely spark a refugee crisis

A full Russian invasion could send as many as one to five million refugees fleeing Ukraine, American officials and humanitarian agencies have warned.

“It will be a continent-wide humanitarian disaster with millions of refugees seeking protection in neighbouring European countries,” Agnès Callamard, secretary-general of Amnesty International, said last month.

Poland, which shares a border with Ukraine and is already home to more than a million Ukrainians, would likely see the most refugees. Over the weekend, Polish Interior Minister Mariusz Kaminski said his country was preparing for an “influx of refugees” from Ukraine.

The U.S. military says that the thousands of soldiers deployed to Poland this month are prepared to assist with a large-scale evacuation.

“Assistance with evacuation flow is something they could do, and could do quite well. They are going to be working with Polish authorities on what that looks like and how they would handle that,” Pentagon spokesperson John Kirby said earlier this week.

At the largest scale, a refugee crisis would not be contained to Europe – the U.S. would likely see refugees seeking asylum here, too.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))