One early morning, Jason Vaughn was going for a jog in his Brunswick, Georgia community. Vaughn, a football coach and history teacher at Brunswick High School, spotted his favorite player and student who had attended the school in years past.

Vaughn had the idea to catch up to his former student and surprise him. The runner he was trying to catch was Ahmaud Arbery, who was also on a routine run. The two had a close relationship and a history of joking on each other.

“Every teacher has a favorite kid they absolutely love that reminds them why they got into the profession,” Vaughn said. “And so ‘Maud was that for me.”

Attempting to close the gap between them, Vaughn hit a sprint. But the 42-year-old wasn’t able to catch up with him, so he eventually gave up. That was the last time he saw Ahmaud before he was killed on a later date, Feb. 23, 2020.

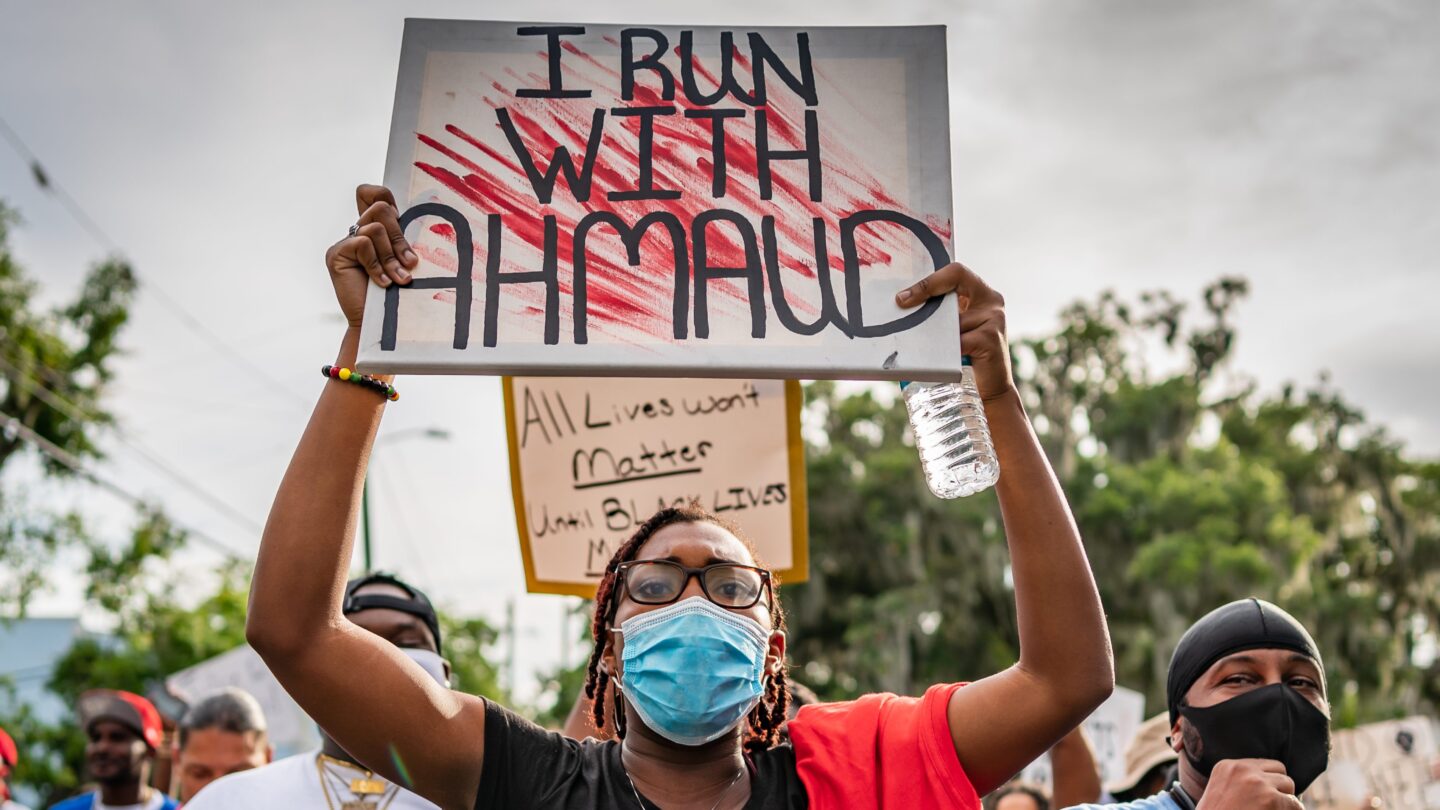

“And I explained to my brother, I said, ‘Man, I got tired on that day. But I will not get tired of seeking justice for ‘Maud,'” Vaughn says. “I don’t run with my endurance. I run with that great heart and endurance that ‘Maud had.”

From this story, the hashtag #IRunWithMaud was created. It went viral in early May, triggering the beginning of a summer blistered with calls for social change and protests asserting that Black lives do indeed matter.

The 2:23 Foundation was founded by Vaughn and three other Brunswick natives with a mission of uplifting and educating Black and Brown communities and fighting against systemic injustices.

“We brought a community that was hurting together for a cause that’s greater than all of us,” Vaughn says. “And calls to ensure a better future, a safer future for everyone in our community.”

On Feb. 23, 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was taking an afternoon run when three men chased him down. According to the police report, they thought he burglarized a home, though video footage of the incident differs. He was shot multiple times and died on the spot.

“I found out a way that no loved one should,” Vaughn says. “I found out through social media.”

On Feb. 27, The Brunswick News published a vague article about the shooting that didn’t provide any answers he was looking for. On April 1, the local newspaper received a copy of the police report in which more details were released about the incident, but not enough details were published for Vaughn.

“It frustrated me so much,” he says. “I’m physically in my house upset. I’m yelling, I’m grunting. And I just feel so much pain, just so much anger.”

Eventually, the 2:23 Foundation was created so nobody forgets the day Ahmaud’s life was taken, he says. But it took a lot of work for the Foundation to get where they are today, with a community behind them and far-reaching support.

Samantha Gilder, a Brunswick native and executive assistant for the Foundation, had been there since the group’s conception.

In early April, Vaughn held a Facebook livestream with his brother and co-founder of the foundation, John Richards. They were looking for someone who could help draft an open records request for the police report, and that’s how Gilder first got involved. That weekend, they sent in over 150 records requests, she says.

“And that kind of started my relationship with these guys that you know, at that point, it was purely just online, people that I was helping that I didn’t meet,” she says. “But it has formed and blossomed and turned into just becoming an actual team member.”

Gilder never knew Ahmaud personally. However, she knew of Travis McMichael because they were in similar circles, so at points throughout her life, she’d be around him. In addition to being the only white person and woman in the group, she sees it as an “interesting dichotomy.”

Nevertheless, Ahmaud’s death weighed heavy on her, she says. Partly because of her relative proximity to McMichael.

“It affected me in a way that I wasn’t fully prepared for, but I knew that I needed to see that feeling through,” Gilder says. “I knew that this was something that not only for myself but for our community that needed to be reckoned with.”

On Feb. 23, 2021, the 2:23 Foundation is hosting a virtual run dubbed #FinishTheRun.

“You know, the run that Ahmaud intended to take on that day and was never able to finish,” she says.

They encourage participants to run, walk or bike 2.23 miles to honor the memory of Ahmaud. Registration costs $23, and all proceeds go to scholarships and mentorships benefiting Black and Brown students. They will also hold a candlelight vigil in support of Ahmaud’s family.

A New Purpose

Demetris Frazier is a cousin and lifelong friend of Ahmaud Arbery. They connected most as teammates playing football together.

“Oh, he’s a great guy … he’s one of those guys that believes in you more than you believe in yourself,” Frazier says.

Last February, Frazier was at work when he received a message from a friend reading, “Maud’s dead.” His initial disbelief led him to text Ahmaud, to which he received no response. But he just assumed he was busy and couldn’t respond.

Soon after, Ahmaud’s mother confirmed that what he had heard was true.

“It just hurt, and that was just a devastating day,” he says. “And I just didn’t know where to go, I didn’t know the place to be, and I was just hurting.”

Similar to Vaughn, Frazier was searching for answers to no avail. He says he never knew Ahmaud to put himself in a position to be killed or hurt in any way, so the talk about him being a burglary suspect wasn’t making sense. He knew something wasn’t right.

The Brunswick community was also hesitant to believe what was being circulated in news articles. But some people did believe it, he says, and saw it as another instance of a Black man “killed for doing something stupid.”

“But when that video dropped, it hit different here,” he says.

The video of the shooting began circulating in early May and sparked a stark moment of clarity for many in Brunswick and around the world.

On May 7, Travis and Greg McMichael were arrested, charged, and booked into Glynn County Jail. But Frazier says it wasn’t a “breath of fresh air” for him. The Foundation, which was then known as the I Run With Maud organization, still had work to do.

“And [there are] many things that have happened across the world that are probably similar to this where, you know, families don’t know what to do,” Frazier says. “Some of them just don’t have the fight or the resources and the drive to do it. But we felt like we cannot let this happen.”

An integral part of the strategy for the Foundation is John Richards, brother of Jason Vaughn. As a lawyer, Richards helped the group better understand everything that was going on and communicate it to the Brunswick community too.

“I just knew I wanted justice,” Frazier says. “So, John was pretty much needed to us, man. And still is. He set out actual steps for us to put out to the community.”

Richards first heard of Ahmaud’s death through his brother. He says the story deeply impacted him because of his roots in Brunswick and the realization that it could’ve been his own son getting killed.

“That combination of those elements really personalized it for me, even though I didn’t know [Ahmaud] personally,” Richard says.”

It was Richards’ idea to host the Facebook livestream where Samantha Gilder was first introduced to them. The three of them, along with Frazier, took on a 4-step plan of action as directed by Richards.

First, they were to call and email the district attorney as much as possible. Second, submit the records requests for the full police report. Third, pressure the district attorney’s office and the police chief to make arrests. And lastly, do everything they can to get attention from national media.

All four steps were achieved, and in the fall they officially became the 2:23 Foundation. For the November general election, they engaged with voters in their community to vote out Jackie Johnson, the then-district attorney in Brunswick who ran unopposed in the position for 24 years.

“We went from, how can we move from fighting fires to preventing fires, so looking for ways that we can in the future prevent something from happening,” he says. “And we thought that creating an organization that works to empower youth and young people towards social justice and advocacy work was going to be the best way to impact our city locally.”

Frazier says that over the past year, the Brunswick community has come together more than ever. Though everyone is “obviously” cautious, he adds.

“We’ve truly come together as a community in trying to keep everybody up,” Frazier says. “It’s not easy because you still have that bad bunch, but everybody’s doing good for the most part.”

For him, an important part of the Foundation is helping others through scholarships, offering financial stability, and providing resources to help students get to college and graduate. And although the continued support from others feels amazing, he says, grief still weighs on him and Ahmaud’s family.

“Some days you can sleep, some days you can’t,” he says. “But I think what’s been giving me the biggest push is family, especially with ‘Maud’s dad I’ve spent a lot of time with.”

For Ahmaud to have his life taken away because of the color of his skin, Frazier says, is a different type of pain. Yet, he has a son of his own and says he still can’t imagine the pain that Ahmaud’s father has felt.

“It’s tragic and bad, but what are we gonna do about it to stop it and to help change lives?” he says. “And that’s [by putting] future lawyers, future politicians in certain places and put them in school to help them become these people we depend on.”

For a deeper exploration of Ahmaud Arbery’s story, listen to WABE’s podcast, “Buried Truths.” Hosted by journalist, professor, and Pulitzer-prize-winning author Hank Klibanoff, season three of “Buried Truths” explores the Arbery murder and its direct ties to racially motivated murders of the past in Georgia.