Two things can be true at the same time. We’re in a time of backlash to ideas that challenge white America’s perception of itself, and we’re also living through a great reevaluation of what American society can and should look like.

It’s also true that some of the most important leaders on the frontlines of these battles are Black women, people like law professor Kimberle Crenshaw who helped develop the concept of intersectionality and the much debated and maligned and misunderstood critical race theory and a new wave of thinkers picking up that inheritance. Black feminists are also some of the most astute observers and theorists of American mass culture right now. Scholars and writers like Patricia Hill Collins, Joan Morgan, and the late bell hooks have long understood that oppression and injustice is perpetrated and enacted through customs and cultural practices as well as law. At it’s root, Black feminism is an ideology of liberation rooted in Black women’s experience, with the inclusive aim of disrupting oppressive social hierarchies for all people. Black feminist theory is arguably now a key part of how all of us make sense of the world.

At the same time, the kind of cultural analysis that Black feminists promote continues to be controversial. Between the numerous attacks on library collections and school curricula — a 2021 NBC News analysis found at least 165 local and national groups are trying to disrupt or block lessons on race and gender — and the recent passing of the foundational cultural theorist bell hooks, questions of culture and identity bubbled up with renewed urgency.

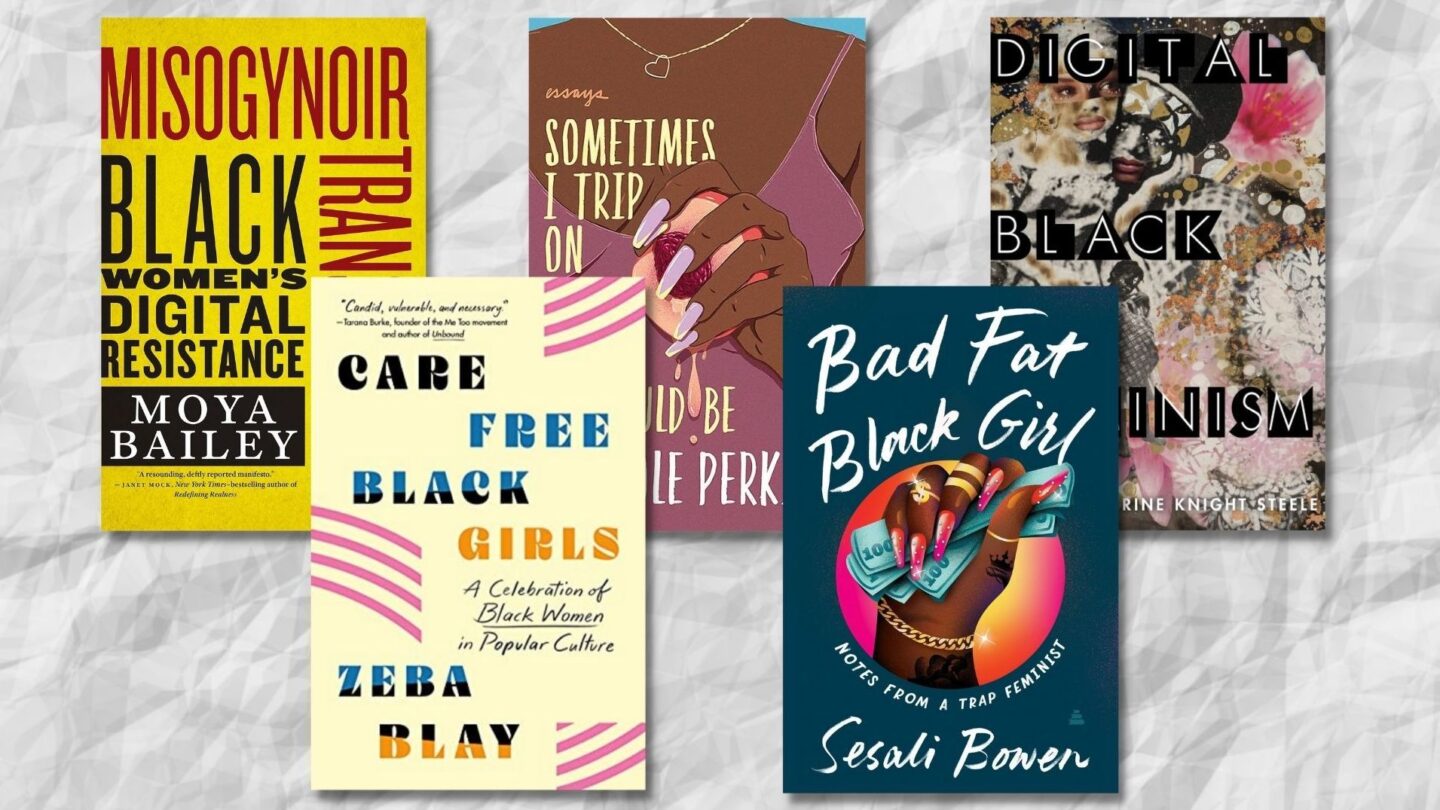

A silver lining in this time of contradictions, of creativity, and precarity, has been the bumper crop of new books at the intersection of Black feminist thought, culture, and politics. Even better, this great flowering is not isolated to the proverbial ivory tower. With Nichole Perkins’ popular memoir Sometimes I Trip On How Happy We Could Be and Zeba Blay’s essay collection Care-Free Black Girls, I was struck by how vibrant, wide ranging and central the conversation is right now around Black women, feminism and culture. Looking at these books it’s immediately clear how relevant they are to people’s lives.

Choosing a short list from the recent bounty is a daunting task, but these five books stand out in conversation and contrast with each other. Though they target different audiences and sit within different genres of nonfiction – from memoir to cultural analysis to theory – they share certain hallmarks: a celebration of marginalized, unruly Black women and concurrent rejection of the politics of respectability; the not so secret realization that as dissatisfied as we are with our exclusion and distorted depictions, popular culture plays a big role in all our lives; and a keen awareness of the complex connections between representation and reality.

Sometimes I Trip on How Happy We Could Be by Nichole Perkins

No one writes better about the personal relationship between culture and girlhood than Nichole Perkins, a popular cultural commentator and writer. Her first book is a page turner, a singular and seamless blend of memoir and cultural analysis. I found her words heart-wrenching.

As a former host of “The Thirst-Aid Kit,” a podcast aimed at analyzing the intersection of sexual desire and popular culture, the way Perkins writes about her burgeoning sexuality and the awareness of how that’s different when you’re Black is particularly effective. She exposes the pervasive shaming around sex, and how it’s not equally distributed. Societal rules differ by race (for Black girls versus white girls) and gender (for Black boys and Black girls). Too often, Black girls have been relentlessly shamed, and that formative personal experience has been reinforced by the culture.

That experience can be crushing. So, unlike the dearth of love stories for Black girls in film and television when Nichole was growing up: “There were plenty of sassy Black teenagers on television, in characters like Dee Thomas on What’s Happening!! or Tootie on The Facts of Life. These girls always had a smart remark ready on their lips and got plenty of laughs, but just like in real life around my way, every crush they had led to lectures or scolds… Images of white girls in love came easily, but everywhere I turned black girls were warned.”

That passage is just one example of how Perkins’ work blends passion and analysis. My list of highlights is endless. Like in a confessional conversation, albeit one that is as incisive as it is emotional, Perkins is adept at connecting personal experience to cultural and social practices.

Not everything hits perfectly, but there is no doubt that this memoir is very real and candid. The passages where Perkins writes about her family are also especially powerful. One part that just about broke me was Perkins’ discussion with her aunt of Tenessee Williams’ American classic “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof.” Her insights resonated far and wide on her podcast, and readers will nod along to these words as well.

Carefree Black Girls by Zeba Blay

Though the concept spread like wildfire in 2013, the idea of the “carefree Black girl” was always more of an aspiration than reality. It spoke to a hunger and lack in the images and discourse around Black women. As author Zeba Blay notes in her book: “Social media has always been a great place for pretending, for playing, for projecting some idealized version of self. A way to hide in plain sight. I posted the selfie and the hashtag. An attempt to be carefree.”

Expanding on the concept and archetype Blay originated, Blay’s first book is similarly aspirational, but also deeper and more confessional. Carefree Black Girls: A Celebration of Black Women in Popular Culture is “a meditation on a single idea: what it means to be a Black woman and truly be ‘carefree.'” With a clarity of mission that Blay executes masterfully, the book hangs together with admirable cohesion. One of the more personal subjects Blay explores is her struggle with depression, and the role that art and culture plays in her recovery: “Turning to art and turning to Black women has always been the road by which I come back to myself.”

As personal as those revelations are, like the other authors on this list, Blay is also clear on the connections she makes to larger cultural trends and phenomena outside of herself. The stories she relates are specific, but not isolated. Staking a claim and underscoring her point in the most direct way possible, she writes, “Our stories are culturally and historically relevant.”

There’s beauty in Zeba Blay’s style and substance in her ideas. I was struck by the poignance of her plea and how familiar it sounded: “Hopefully, whoever you are, reading this, you find inspiration in that beauty. And hopefully you are reminded that Black women are essential.” That this message pops up so consistently across these books, and that so many of these authors feel it needs to be repeated, speaks volumes.

Bad Fat Black Girl by Sesali Bowen

Both manifesto and memoir, Sesali Bowen’s Bad Fat Black Girl is another standout. It’s written from the perspective of someone who’s both a media scholar and activist, and it shows.

Like the other authors, Bowen weaves together observations about cultural expression with broader social attitudes and ideas. But there’s more of an urgency and grit and an irrepressible, profane irreverence to a book titled “Bad Fat Black Girl.” Bowen also brings more of an outsider perspective. She grew up working class and she’s not trying to aspire or fit into white dominated “mainstream” culture.

Influenced by Joan Morgan’s When Chickenheads Come Home to Roost (about reconciling feminism and hip-hop) and trap music, Sesali Bowen weaves together feminist theory and hip-hop analysis from the perspective of someone who loves and lives for it. Citing trap artists like Yo Gotti, Gucci Mane and Travis Porter alongside Megan Thee Stallion and Cardi B, Bowen articulates a vision of what she calls “trap feminism,” a music and street-inflected ethos of empowerment. Despite trap being known as reductive, Bowen refused to “accept the idea that no good could come out of trap music. I wanted to reconcile the fact that some of my favorite trap songs made me, a queer Black woman, feel good, proud, and even inspired.”

Bowen also effectively argues that a lot of what is dismissed as “ratchet” or uncouth is really a conscious aesthetic of rebellion, a way of eschewing still white-centered patriarchal conventions that fail girls like herself. With behavior and style choices that make sense for their environment and circumstances, “ghetto girls,” she says, perform gender in rebellious ways that are often disrespected and yet envied and eventually emulated.

Bowen is a versatile and agile commentator, equally convincing and expert in her explication of the idea of the “bad bitch” as an expression of power in hip-hop and citing bell hooks on why beauty is a “politicized concept” that maintains what hooks called “imperialist, capitalist, white supremacist patriarchy.” The latter may seem like a long list of “isms” and labels, but Bowen shows that these dimensions of social hierarchy and control have real-world implications. She names and shames a system of cultural gatekeeping in which hip-hop and even Bowen’s beloved trap culture is complicit, assigning value and affording respect and opportunity to a select group. And, in keeping with that, as Bowen shows, even when Black girls are celebrated, it’s within a narrow range of acceptable images of Black femininity. Existing outside those “aesthetic rules” (as Bowen herself does) has consequences:

“It means that you’ve committed an egregious act against the social order. Women who find themselves too far away from the center of beauty norms are often treated as if they’ve committed treason, our aesthetic a public-facing betrayal of our refusal to conform…”

Complicating that analysis, Bowen also calls out the classism and cultural biases even within Black media circles where so many of her colleagues come from privilege and “have had to untangle their Blackness from the web of whiteness they were socialized in.” This is one reason Bowen is powerful; she takes no prisoners. Going against every tide, Bowen’s trap feminism enthusiastically celebrates “ghetto girl culture.” More than reconciling feminism with hip-hop, she marshalls its power.

Misogynoir Transformed: Black Women’s Digital Resistance by Moya Bailey

Known for coining the term misogynoir, a portmanteau of the words “misogyny,” meaning the hatred of women, and noir, the French word for Black, Northwestern professor Moya Bailey has already made a mark on the landscape of American culture that extends beyond academia. The term and its implications have penetrated popular consciousness. With her first solo-authored book, Bailey expands this impact.

As seen in the books on this list, the work of Patricia Hill Collins has influenced many writers in the Black feminist tradition, but with Bailey, that legacy is more direct. Building on works like Collins’ Black Feminist Thought and bell hooks’ Black Looks, Bailey expands our understanding of the link between media portrayals of Black women, which people like to think of as merely symbolic or superficial, and real world, material consequences:

“…the media that circulate misogynoir help maintain white supremacy by offering tacit approval of the disparate treatment that Black women negotiate in society. Whether the Jezebel, mammy, Sapphire, and later the ‘welfare queen’ or even the ‘strong Black woman’ archetype, misogynoiristic portrayals of Black women shape their livelihoods and health.”

In other words, contrary to those who would dismiss the weight of culture, Black feminist theory “articulates the power of the image.” By shaping the way that society views marginalized groups and how we view ourselves, cultural images help shape our social relations.

By design and necessity, this project is inherently political. Like Collins before her, Bailey’s work is significant on its own. But such work also adds essential perspective and depth to the efforts of political scientists like Angie Hancock, author of “The Politics of Disgust” whose research established in quantifiable terms the impact of the welfare queen image on public policy debates around the social safety net. Today, it’s hard to understand American politics without coming to grips with the concepts Bailey’s grappling with.

Bailey’s aims are ambitious. She’s not interested in just shining a light on misogynoir; she’s interested in its destruction. In a voice that is scholarly yet accessible, she tackles media culture from television and film to Tumblr to YouTube web series, to hashtags, revealing how different media contribute to, transform and/or challenge the pervasive circulation of misogynoir and, importantly, how Black people deploy digital activism to resist. Though expansive, Bailey’s scope is also strategic; she privileges those too often marginalized in feminist conversations: “Black women as well as Black nonbinary, agender, and gender-variant folks’ work and voices.” The penultimate chapter, “Alchemists in Action against Misogynoir, ” which is Bailey’s most personal, focuses on Tumblr. It’s a particular treat.

Digital Black Feminism by Catherine Knight Steele

In Digital Black Feminism, Catherine Knight Steele centers Black women unapologetically within the study of digital culture. “Digital Black feminism is a mechanism to understand how Black feminist thought is altered by and alters technology,” she writes. This work has multiple dimensions. First and fundamentally, Steele exposes the frequent oversight of Black women’s contributions as a distortion that limits deeper understanding of the dynamics of the digital world. As Steele establishes, Black women’s involvement in digital spaces has been broad-based, influential and persistent. Understanding that digital culture requires getting this part of it right.

So one contribution of Steele’s work is as a course correction to the work that’s been done before. At the same time, this book also recognizes and builds on the significant inroads made by scholars studying race and technology including Safiya Noble (Algorithms of Oppression,) Sarah Florini, and Andre Brock.

Steele has two core aims. First, she positions Black women online as central to the future of communication technology just as they’ve been central to its past. Second, per its title, Digital Black Feminism traces and critically examines a evolutionary shift in Black feminism thought, one driven and enabled by new technology.

As both a researcher and a member of these spaces, she’s well-equipped for these tasks. Diving into a wide-ranging digital archive six years in the making, she demonstrates how online spaces expand and shape the work of Black feminist liberation while making insightful connections to the Black thinkers and writers that came before. In one chapter, Steele explores the parallels between hip-hop’s formative influence on an earlier generation of feminists and the role of digital technology in Black feminism today, noting how money changed both of those relationships. For a book with heft, it strikes an impressive balance of accessibility and intellectual innovation.

A slow runner and fast reader, Carole V. Bell is a cultural critic and communication scholar focusing on media, politics and identity. You can find her on Twitter @BellCV.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))