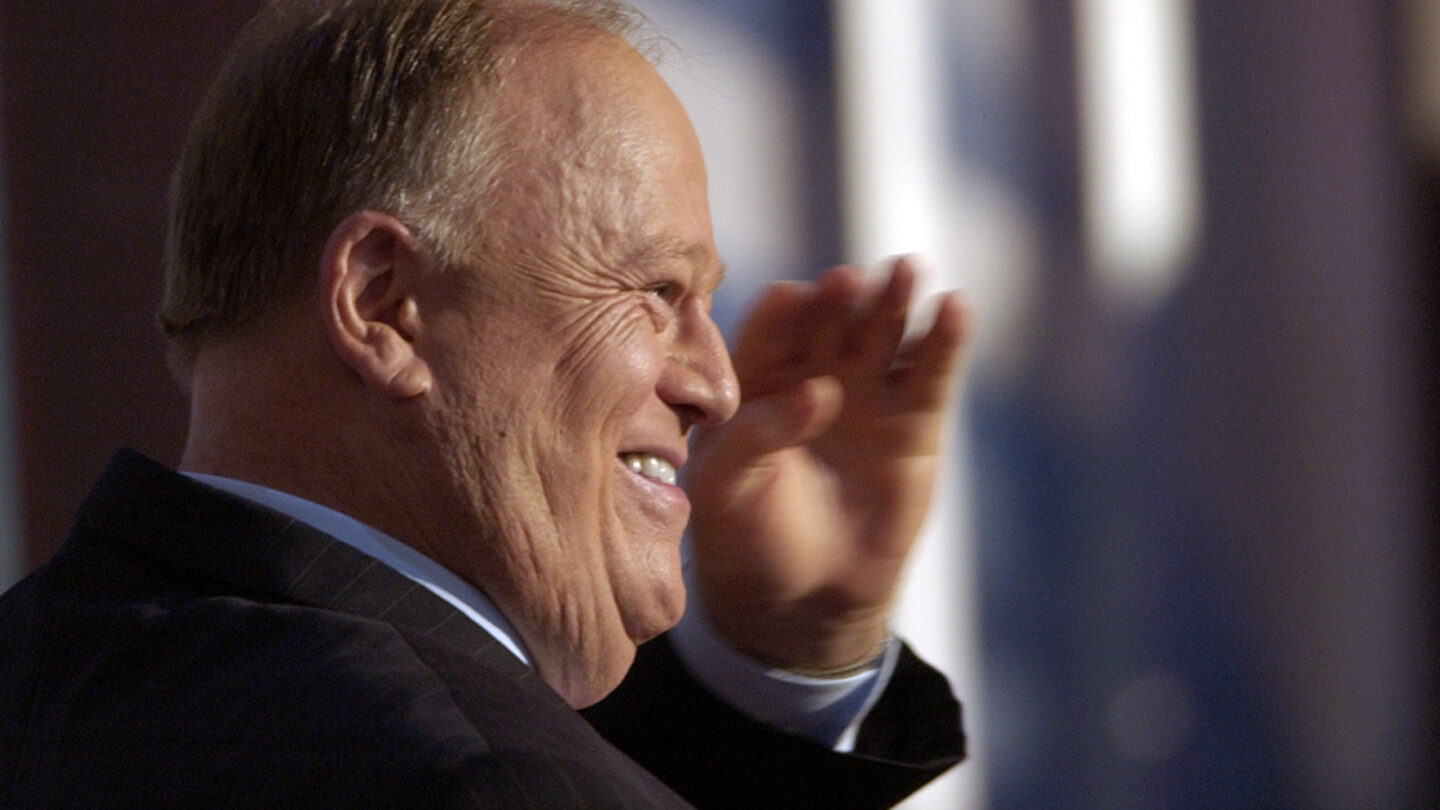

President Joe Biden and three former presidents paid tribute Wednesday to late Veterans Administration chief and U.S. senator Max Cleland, who lost limbs while serving in Vietnam.

Biden called Cleland a hero who “exemplified the best of the American spirit.”

Former President Barack Obama said Cleland was “someone who defied impossible odds to become one of our nation’s finest public servants.”

“Max wore the physical and emotional scars of war, but he never lost his drive to do right by the people of Georgia and Americans everywhere,” Obama said.

Obama, Biden and former presidents Bill Clinton and Jimmy Carter were not present, but sent letters that were read by Carter’s grandson, Jason Carter.

Cleland died of congestive heart failure in November at the age of 79, but his memorial service was delayed because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

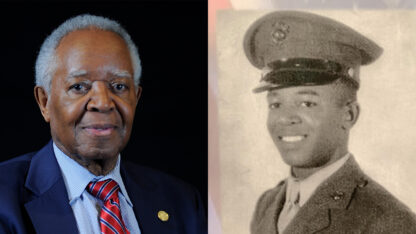

Cleland was a U.S. Army captain in Vietnam when he lost his right arm and two legs while picking up a fallen grenade in 1968. He blamed himself for decades, until he learned that another soldier had dropped it. He also spent many months in hospitals that were ill-equipped to help so many wounded soldiers.

Speakers at the Atlanta church recalled how Cleland struggled to get up each morning and dress, but still remained buoyant and jovial.

“He was a man defined not by what had happened in his life, but he was defined by courage and maybe even more than that by one principal: to make a better world,” former U.S. Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel said. “He lived that everyday. Yes, he had his demons but he dealt with them in a positive, inspirational way that set a model for all of us.”

Hagel, a Republican, said Cleland’s example was especially important today amid the country’s political polarization. Cleland was a Democrat.

“Because he never let that division or polarization ever affect his personal relationships, his love of his country, his love of his friends and brothers, Republican or Democrat,” Hagel said.

U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate and fellow Vietnam veteran John Kerry also sent a written tribute in lieu of attending in person.

Kerry said Cleland came to Iowa in 2003 during Kerry’s presidential run and lifted up his flagging campaign staff, telling them if they didn’t go out and knock on doors in the three-foot snowdrifts he would do it himself.

“And he told them, ‘If you see my wheelchair tracks in the snow and they stop, start digging,'” Kerry said.

Other men would not have recovered from the tragedy Cleland suffered in Vietnam, former Georgia Gov. Roy Barnes said. He called Cleland a “force of nature.”

“His disabilities became his strengths. His struggles became our inspiration,” Barnes said. “After all these years, I’m still amazed at his sacrifice and service, and I was always humbled to be in his presence.”

Fellow veterans cheered when Carter appointed Cleland to lead the Veterans Administration, a post he held from 1977 to 1981. The VA and the wider medical community recognized post-traumatic stress disorder — what had previously been dismissed as shell shock — as a genuine condition while Cleland was in charge, and he worked to provide veterans and their families with better care.

Cleland left Washington after Carter lost reelection, and in 1982 was elected Georgia’s Secretary of State, a post he held for a dozen years. Then he won the Senate seat of the retiring Sam Nunn.

Historian Douglas Brinkley, a friend of Cleland’s, said Cleland “never forgot a single Vietnam vet his entire life.”

“He wanted to know their back stories, who they dated, how their lives were changed, where they were getting their medical treatment,” Brinkley said.

Brinkley called on the veterans administration to honor Cleland with a memorial in Washington.