Health care providers at the center of a lawsuit challenging Georgia’s six-week abortion ban say the new law has limited their ability to care for patients whose wellbeing may be at risk.

But attorneys for the state invited out-of-state medical providers – including a Texas obstetrician and gynecologist whose credibility was questioned by a Florida judge this summer – to make the case that Georgia’s law leaves room for physicians to use their best judgment when faced with a medical emergency threatening the life of a pregnant woman.

The debate over the narrow exceptions included in Georgia’s abortion ban were at the center of a two-day proceeding focused on whether the state’s six-week ban on most abortions runs afoul of the state constitutional right to privacy.

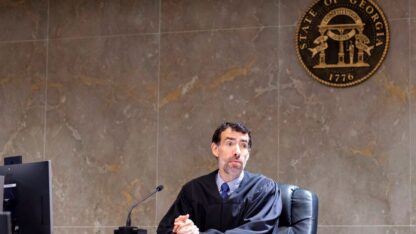

The trial played out in downtown Atlanta – just a couple blocks away from where the law was passed in 2019 – in Fulton County Superior Court Judge Robert C. I. McBurney’s courtroom. Both sides will file more briefings next month, pushing a ruling on the controversial law out beyond the Nov. 8 election.

The attorneys representing the health care providers and abortion rights advocates who are challenging the law argue the law is far too restrictive and has left health care providers skittish to perform an abortion that may qualify under the exceptions allowed.

They argue the law, which took effect in July after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, should be thrown out and the issue put on the ballot for voters to decide.

Under the law, medical providers risk being charged with a felony – and potentially losing their license.

“The medicine hasn’t changed, and the counseling and the risks are the same,” said Dr. Martina Badell, who is the director of the Emory Perinatal Centers. “The difference is that now as (health care) providers in the state, we have to balance the risks of criminal prosecution if we were to proceed with an abortion versus what we think might be the best medical decision that a patient makes for her body.”

Badell said she has stopped offering what is called a multifetal pregnancy reduction, which is a procedure that reduces the number of fetuses if, for example, a woman is expecting triplets.

The lack of certainty surrounding what exactly qualifies as a medical emergency has left Badell feeling like her hands are tied, she said.

“It is heartbreaking to tell someone – and if they’ve come to the conclusion that that’s the right thing for their family – that I have to say, ‘Well, I wish you the best and good luck. I hope you have the resources and the wherewithal to navigate getting the care that you desire,’” she said.

Even more harrowing, she said, is trying to decide when a threat to a woman’s life is sufficient for medical intervention under the law.

“‘Necessary to prevent a death’ – is that a death that we think is 1% likely? 10% likely? 20%?” Badell said. “It’s unclear at what risk of death to the pregnant person would qualify as ‘necessary.’”

But a North Carolina physician testifying in defense of the law argued the restrictions do not prevent Georgia physicians from performing a multifetal pregnancy reduction since not doing so could potentially harm a woman’s reproductive system.

In addition to life-threatening situations, Georgia law allows an abortion if it is deemed necessary to prevent “substantial and irreversible physical impairment of a major bodily function of a pregnant woman.”

The law also still allows abortions if the fetus is considered “medically futile” based on “reasonable medical judgement,” which critics of the law argue is also too vague.

“We make gut-wrenching decisions all day long every day,” said Dr. Jeffrey Wright, a specialist in maternal fetal medicine who does not practice in Georgia. “I mean, when I answer that call, it ain’t gonna be no kitty or puppy, right? It’s gonna be another gut-wrenching decision and that’s what we do as maternal fetal medicine specialists.”

Anti-abortion advocacy ties

Another witness for the state, Dr. Ingrid Skop, argued caring for pregnant women has always been a risky field.

Skop is the director of medical affairs for the Charlotte Lozier Institute, which is affiliated with the anti-abortion advocacy group Susan B. Anthony Pro-Life America. A Florida judge questioned Skop’s credibility after she defended the state’s 15-week ban this summer.

“It is part of our job to recognize we may make a decision and someone may second guess that decision,” Skop said Tuesday in the Atlanta courtroom. “So that has always been the case.

“I understand the word ‘felony’ is scary. I get that. But there is nothing that this law is telling doctors to do or not do that we haven’t always done. We’ve always intervened when we needed to to save a woman’s life.”

Another supporter of Georgia’s law, Priscilla Coleman, also brought her controversial argument that abortions are harmful to women’s mental health. Georgia’s law excludes psychiatric illnesses from the medical emergency exception, including if the woman is at risk of committing suicide.

“You’re likely to feel even worse if you abort. It’s not going to fix your problem,” Coleman said.

The plaintiffs’ attorneys, who are with the ACLU of Georgia and the Center for Reproductive Rights, also cast doubt on Coleman’s credibility by showing some of the reviewers of her study are affiliated with anti-abortion advocacy groups.

The judge questioned the rationale for the mental health exclusion in the law.

“But if the medical professional – a psychiatrist – the medical professional determined, ‘Hey, this is someone who will not feel better if she carries to term, and it’s my diagnosis that she’s likely going to kill herself if she is not able to end the pregnancy.’ How is that a better outcome to say that’s not a medical exception? I’m just trying to understand the data that would support that outcome,” McBurney said.

Coleman dismissed the scenario as an individual case.

“When laws are made, they should be made to address what’s best for most individuals in the state,” she said.