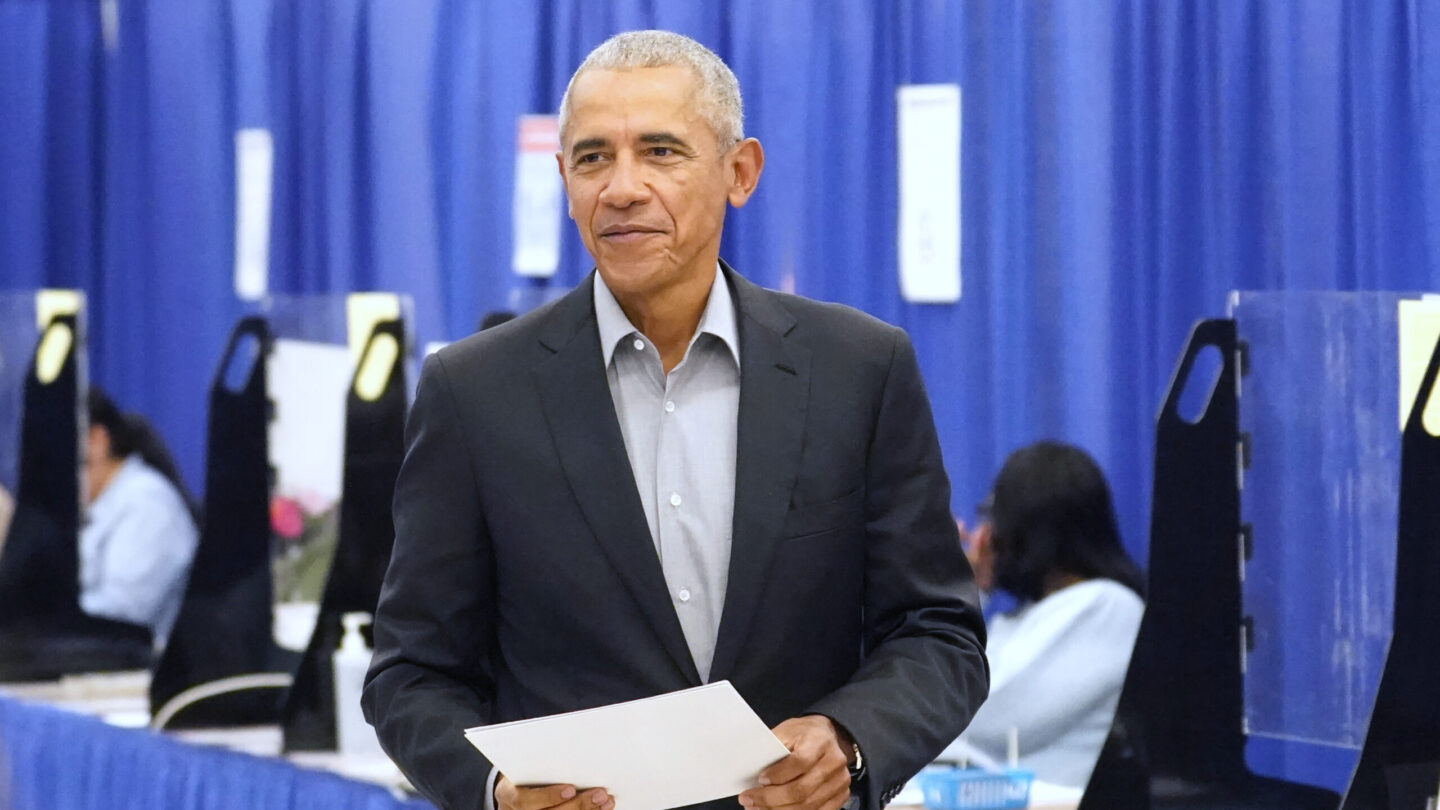

Barack Obama is trying to do something he couldn’t during two terms as president: help Democrats succeed in national midterm elections when they already hold the White House.

Of course, he’s more popular than he was back then, and now it’s President Joe Biden, Obama’s former vice president, who faces the prospects of a November rebuke.

Obama begins a hopscotch across battleground states Friday in Georgia, and he will travel Saturday to Michigan and Wisconsin, followed by stops next week in Nevada and Pennsylvania.

The itinerary, which includes rallies with Democratic candidates for federal and state offices, comes as Biden and Democrats try to stave off a strong Republican push to upend Democrats’ narrow majorities in the House and Senate and claim key governorships ahead of the 2024 presidential election.

With Biden’s job approval ratings in the low 40s amid sustained inflation, he’s an albatross for Democrats like Sens. Raphael Warnock of Georgia and Catherine Cortez Masto of Nevada. But party strategists see Obama as having extensive reach even in a time of hyperpartisanship and economic uncertainty.

“Obama occupies a rare place in our politics today,” said David Axelrod, who helped shape Obama’s campaigns from his days in the Illinois state Senate through two presidential elections. “He obviously has great appeal to Democrats. But he’s also well-liked by independent voters.”

Neither Biden nor former President Donald Trump can claim that, Axelrod and others noted, even as both men also ratchet up their campaigning ahead of the Nov. 8 elections.

“Barack Obama is the best messenger we’ve got in our party, and he’s the most popular political figure in the country in either party,” said Bakari Sellers, a South Carolina Democrat and prominent political commentator.

Obama left office in January 2017 with a 59% approval rating, and Gallup measured his post-presidential approval at 63% the following year, the last time the organization surveyed former presidents. That’s considerably higher than his ratings in 2010, when Democrats lost control of the House in a midterm election that Obama called a “shellacking.” In his second midterm election four years later, the GOP regained control of the Senate.

Swimming against those historical tides, Biden traveled Thursday to Syracuse, New York, for a rare appearance in a competitive congressional district. After months of Republican attacks over inflation, he offered a closing economic argument buoyed somewhat by news of 2.6% GDP growth in the third quarter after two previous quarters of retraction.

“Democrats are building a better America for everyone with an economy … where everyone does well,” Biden said.

Yet Lis Smith, a Democratic strategist, said Obama is better positioned to take that same argument to Americans who haven’t decided whom to vote for or whether to vote at all.

“If it’s just a straight-up referendum on Democrats and the economy, then we’re screwed,” Smith said, acknowledging that no incumbent party wants to run amid sustained inflation. “But you have to make the election a choice between the two parties, crystallize the differences.”

Obama, she said, did that in the 2008 and 2012 presidential elections “by winning over a lot of working-class white voters and others we don’t always think about as part of the ‘Obama coalition.’”

He couldn’t replicate it in midterms, but he’s not the president this time. Smith and Axelrod said that means Obama can more deftly position himself above the fray to defend Democratic accomplishments, from the specifics of the Inflation Reduction Act to the COVID-19 pandemic relief package that many Democrats have avoided touting because Republicans blame it for inflation. Smith said Obama can remind voters of years of Republican attacks on his 2010 health care law that now seems to be a permanent and generally accepted part of the U.S. health insurance market.

Beyond those policy arguments, Sellers noted that Obama, as the first Black president, “connects especially with Black and brown voters,” a bond reflected in the opening days of his itinerary.

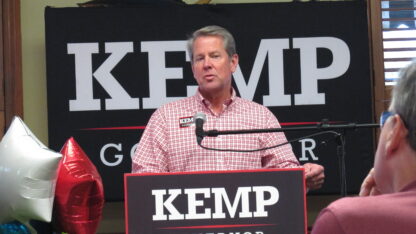

In Atlanta, he’ll be on stage with Warnock, the first Black U.S. senator in Georgia history, and Stacey Abrams, who’s vying to become the first Black female governor in American history. Warnock faces a stiff challenge from Republican nominee Herschel Walker, who is also Black. Abrams is trying to unseat Republican Gov. Brian Kemp, who narrowly defeated her four years ago.

In Michigan, Obama will campaign in Detroit with Gov. Gretchen Whitmer, who is being challenged by Republican Tudor Dixon, and in Wisconsin he’ll be in Milwaukee with Senate candidate Mandela Barnes, who is trying to oust Republican Sen. Ron Johnson. Each city is where the state’s Black population is most concentrated. Obama’s Pennsylvania swing will include Philadelphia, another city where Democrats must get a strong turnout from Black voters to win competitive races for Senate and governor.

With the Senate now split 50-50 between the two major parties and Vice President Kamala Harris giving Democrats the deciding vote, any Senate contest could end up deciding which party controls the chamber for the next two years. Among the tightest Senate battlegrounds, Georgia, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania are three where Black turnout could be most critical to Democratic fortunes.

Plans have been in the works for Obama and Biden to campaign together in Pennsylvania, though neither the White House nor Obama’s office has confirmed details.

A wider embrace for Obama is a turnabout from his two midterm elections. But it’s at least partly a rite of passage for former presidents. “Most of them — maybe not President Trump, but most of them — are viewed more favorably after they leave office,” Axelrod said.

Notably, during Obama’s presidency, former President Bill Clinton was the in-demand surrogate heavyweight, especially for moderates trying to survive Republican surges in 2010 and 2014. Clinton was a pivotal voice for Obama’s reelection effort in 2012, with Obama dubbing him the “secretary of explaining stuff” after Clinton’s sweeping endorsement address at the Democratic convention as Obama was locked in a tight contest with Republican Mitt Romney.

“Bill Clinton was the MVP for us in 2012,” Axelrod said.

Now, Clinton is two decades removed from the White House, and the #MeToo movement has forced some people to reevaluate his history of sexual misconduct allegations.

“It’s always been dicey to bring in national Democrats in a midterm, and it doesn’t help when they bring a lot of baggage,” Smith said of Clinton.

Axelrod was more circumspect, saying simply, “It’s a different time.”

But he said Obama and Clinton have a similar approach.

“What Clinton and Obama share is a kind of unique ability to colloquialize complicated political arguments of the time, just talk in common-sense terms,” Axelrod said. “They’re storytellers. I think you’ll see that again when he’s out there.”