Finding Your Genealogical Roots Takes Digging, Patience

Through genealogical research, you can find out – or at least take a good guess at – the connections that brought hundreds of men and women together across borders and oceans over time, to create you.

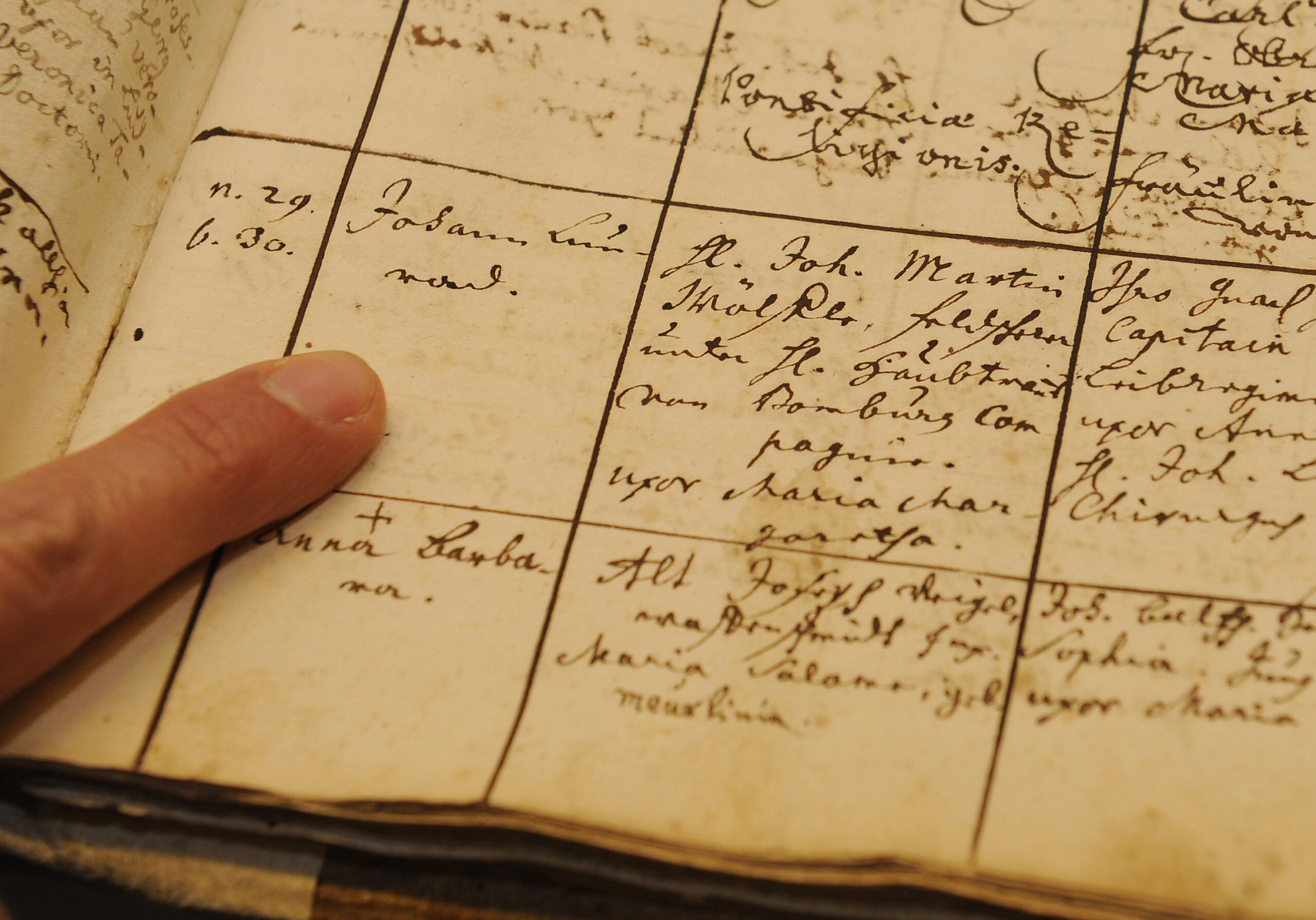

DANIEL MAURER / ASSOCIATED PRESS

This is part of WABE’s ongoing series “Finding Your Roots.”

“Finding Your Roots With Henry Louis Gates Jr.” airs Wednesday at 6 p.m. on PBA30 TV with an encore Saturday at 7 p.m. Watch a preview of Season 3, and see the full schedule at www.pba.org/roots.

In the “nature versus nurture” debate of human identity, the “nurture” part is pretty easy to figure out. You likely know how and where you grew up, and by whom.

But how much do you really know about the sprawling map of ancestors whose DNA is written into your “nature”? And how much does your great-great-great grandmother really have to do with your eye color or ability to roll your tongue?

Through genealogical research, you can find out – or at least take a good guess at – the connections that brought hundreds of men and women together across borders and oceans over time, to create you. But while shows like PBS’ “Finding Your Roots” or commercials for genealogical sites like Ancestry.com may make it look easy to discover the biographies of your ancestors, the process of figuring out one’s personal history is anything but.

Following The Paper Trail

Sabin Streeter, executive producer of “Finding Your Roots,” said that, under ideal circumstances, a single storyline of “Finding Your Roots” would take three months. That’s if the show subject had an easily identifiable ancestral line, likely within North European aristocracy. And that’s with the show’s resources and contacts with genealogists across the globe.

“I assumed it would be easier,” Streeter said about the research his team conducts. Streeter had no prior experience with genealogical research before his work on “Finding Your Roots.”

According to Streeter, the process starts out with a conversation. The subject of the research explains all they know about their family history, and then researchers speak with other members of the family. Streeter said there is generally at least one person in every family who is interested in the family’s background, or a “family Bible” of sorts.

From those conversations, researchers can begin looking into document archives, like Ancestry.com, where census records, ship logs, property deeds and any other official papers might be stored. For more recent generations, genealogists rely more on the oral family histories, since fewer documents are publicly available. The earliest U.S. Census available for public use is from 1940.

Streeter said much of the research involves testing the family’s lore against the paper trail. The stories that are passed from generation to generation may take on some juicy but untrue details, while sometimes written documents may lead a researcher astray.

“It is so, so overwhelming how many records there are and how many people’s names are similar,” Streeter said.

Additionally, if one’s ancestors were lower class or immigrants to America, it would have been likely they could not read or write in English. Name spellings can change from document to document, and sometimes surnames morph as they’re passed down to new generations. Some cultures, like those of Arabic countries, use a naming system different than the European convention.

Perhaps the biggest barrier to uncovering one’s ancestors is American history itself. Since census and financial records most often applied to upper class, white men, records of anyone outside that category can be difficult to follow. Records of women and their familial lines are harder to track than those of men.

For African-American subjects, the ancestral line often stops abruptly at the year 1870. That was the first U.S. Census taken after the end of the Civil War, and it contains the first detailed description of America’s black population. Before that year, the only records of the majority of the country’s black population would have been the ownership records of slaveholders, in which slaves were listed alongside livestock – as property – by age, gender and whether they were “black or mulatto.”

It is possible to trace one’s slave ancestor’s further back if there is a strong oral history and dependable records, but that is often not the case.

“In a lot of cases, they just sort of fell through the cracks,” Streeter said of American slaves.

Streeter said other ethnic backgrounds, like those of Irish and Eastern European Jewish ancestry, also have notoriously poor records due to persecution and violence.

“You learn a lot about various parts of the world, how they treated human beings through genealogy,” he said.

Since America has historically been a destination from immigrants who are fleeing from worse conditions, Streeter said it is common to only be able to follow a paper trail back a few centuries. But if a person has roots in nobility – particularly northern European nobility – it could be possible to trace their ancestry all the back way to Charlemagne. That’s because royalty and the aristocracy has depended upon bloodlines for centuries to determine inheritance and succession to the throne.

When able to trace ancestors abroad, Streeter said his team works with local genealogists to find hard documents. Although the amount of material available online is vast, it is nowhere near the totality of all the world’s record-keeping. Hard copies can be subject to physical destruction and carelessness, and it takes a person who knows the local research landscape to know where to look and what is still available.

A successful amateur genealogical researcher, according to Streeter, needs to be part historian and part detective. He describes the process as a kind of sleuthing in which “most of the questions end up not getting answered.”

Reading Our Genetic Material

But recent advancements in science have actually made it easier to answer more and more questions about an individual’s family tree. Genetic genealogy is an increasingly vital tool any person can use to find out more about their own hereditary make-up.

CeCe Moore, DNA consultant for “Finding Your Roots,” said a common misconception about genetic genealogy is that it is a “shortcut” for that laborious process of digging through paper records. She said she and other genetic researchers “use DNA to extend or enrich what we know about somebody’s family tree.”

Moore said genetic genealogists look at three different types of genetic material for their research: Y DNA, mitochondrial (MT) DNA and autosomal DNA.

Only males carry Y DNA, so an analysis of a person’s Y DNA can establish a person’s paternity line, which can – according to Western naming conventions – link a person to a particular surname group.

MT DNA is passed along the maternal line, and evolves very slowly over the course of generations. Moore said it’s not too useful for genealogy, but can help to confirm theories about the geographic specificity of a person’s ancestors.

Autosomal DNA involves the 22 out of 23 pairs of chromosomes in an average person that are not sex chromosomes. Testing for this genetic material has only been available since 2009 – a new scientific development that has, according to Moore, completely changed the ball game.

Since every person receives a percentage of their forebear’s genetic material, autosomal DNA is inherited from a person’s parents, grandparents and great-grandparents. That means a researcher can trace someone’s ancestors three generations back and, with this DNA, they can match one person’s DNA to another’s.

Moore said this process adds a new degree of certainty to research: “DNA doesn’t lie, sometimes the paper trail does.”

Using a combination of these types of DNA testing, an individual can test their own genetic makeup against those of thousands of people in a genealogical database. Moore said Ancestry DNA, Family Tree DNA and 23 And Me make up the “Big Three” of the databases.

With an increasingly vast aggregate of genetic information, these companies can connect an individual to potential relatives – typically, cousins of some degree. Using the database as a reference, they also give an “ethnic estimate,” which presents the percentages of your estimated ethnic makeup.

However, Moore said this testing still needs to be taken “with a grain of salt.” Genetic testing can only connect you to the ancestors from whom you inherited DNA; this can overlook quite a few potential branches on your family tree. And while “ethnic estimates” are, according to Moore, likely accurate when it comes to distinguishing between continents and historically insular ethnic groups, they can’t specify between close geographical locations and nationalities.

“You can’t tell somebody’s family that they’re not German and instead they’re Irish or Scottish,” Moore clarified.

With the introduction of autosomal DNA research and the growth of genealogical databases, Moore said the field will likely advance in huge, nearly sci-fi leaps in recent years. She predicts that eventually people could start using DNA to reconstruct what their ancestors look like and map particular chromosomal traits to specific ancestors. An individual might be able to say for certain that their nose shape, musical talent or patience came from one of their grandparents.

“The potential for genetic genealogy is almost unlimited,” Moore said.

Looking Into Local Resources

Atlanta History Center Senior Archivist Sue VerHoef said there are a number of local sources available to someone looking to start digging into their own past. In addition to city directories, which can locate an ancestor all the way back to 1859, the center also provides access to the Franklin Garrett Necrology database, a survey of over 750 cemeteries in greater Atlanta that has biographical information from about 163,000 white men who died between 1857 and 1931.

She also recommends looking at the state’s archives. Georgia’s state archives and national archives are conveniently located next door to one another in Morrow.

VerHoef stresses the importance of tapping into local genealogical societies in order to get tips and techniques for digging through old records. While much of those records are located online, VerHoef said, digital copies are just “the tip of the iceberg” of what could be found about one’s heritage.

Genealogical research may the form of detective sleuthing and scientific analysis, but VerHoef has one piece of advice for amateur genealogists familiar to any historian: “cite your sources.”