On Friday, Zach Binney, an assistant professor at Emory University’s Oxford College, brought his work stuff to the temple where his six-month old son Jacob goes to daycare. He spent the day working in the temple library instead of his office so he could spend 20 minutes with the baby during midday Shabbat services.

“I love that kid,” he said. “I’m so, so excited that we were able to finally have him. And I’m so happy for my wife as well. This was one of her lifelong dreams. I wanted to do everything that we possibly could to make that happen for her, for us. It took a lot more than we anticipated, but we got it done. And I could not be happier.”

Little Jacob came into the world after his parents’ five-year struggle with infertility.

“They did pretty much everything under the sun that you can imagine, and they never really found much wrong with my wife,” Binney said. “My tests – I’m very open about this, I think it’s really important, especially for men to talk about this – my results were always, if you were grading them, they’d be about a C or a D. So all the doctors kept telling me, you should be able to have kids naturally, we’re not seeing anything here that would prohibit it, but we kept trying, and it kept failing.

Binney and his wife, Amy, turned to in vitro fertilization, or IVF, a process in which an egg is removed from a woman’s body, fertilized in a laboratory and then returned.

In Binney’s case, three rounds of egg retrieval yielded only five viable embryos. The first four failed, including a couple of miscarriages. Binney said the couple felt like they were holding their breath for weeks at a time, hoping for a healthy pregnancy but constantly fearing the worst. By the time doctors implanted the final embryo, Binney had all but given up hope.

“I was totally resigned. I thought we’re just not destined, this just isn’t in the cards for us,” he said. “We were starting to talk vaguely a little bit about adoption or something like that. We were definitely considering alternative plans until he grew. He wasn’t even a particularly well-graded embryo, but he’s the one who came out. And we couldn’t be happier.”

Georgia welcomed just over 126,000 newborn infants in 2019, 1,915, or 1.5% of whom were born with the help of assisted reproductive technology, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data. Assisted reproductive technology includes fertility treatment where eggs or embryos are handled to establish a pregnancy, and IVF is the most common type. Nationwide, 2.1% of infants born in 2019 were from assisted technology births.

But the end of the Roe vs. Wade era has shaken up the industry, and with Georgia’s 2019 abortion law now under appeal, IVF professionals and advocates are worried about the future.

Georgia’s abortion law defines an unborn child as “a member of the species Homo sapiens at any stage of development who is carried in the womb.” The fertilized eggs used in IVF are stored outside the body, which would seem to exempt them, but Barbara Collura, president and CEO of RESOLVE: The National Infertility Association, said she’s not confident the law will protect patients in the state.

“Georgia has been a difficult state for us for many years in terms of how the Legislature over the years has tried to potentially regulate people’s access to IVF,” she said. “This is not our first rodeo in Georgia, but it’s a very new and different day with Dobbs and Roe v. Wade being overturned.”

During IVF, doctors harvest and fertilize multiple eggs, which leads to multiple viable embryos, which are typically frozen at about five days, before they are visible to the naked eye.

“We don’t know enough about the human embryo to know exactly in that petri dish, which one of those embryos is going to produce a baby,” Collura said. “So the goal is to try and create as many embryos as possible and to transfer, one at a time, those embryos, into the woman’s uterus, in the hopes that she gets pregnant. If she doesn’t, then they have another embryo that they can try, and so on.”

If a patient has leftover embryos after they are finished growing their family, they may decide to give them to another couple hoping to conceive, donate them to scientific research or allow them to thaw and be destroyed.

That creates an ethical dilemma for some anti-abortion activists who believe that life begins at the moment of conception.

“You’re going to have people who are going to say, you can’t do abortion, but you can do IVF, people who are going to say, you can’t do abortion, and you can’t do IVF, either, because those are embryos,” Collura said. “So how that shakes out in each state, in each state legislature, is anyone’s guess. I don’t know today how that’s going to shake out and what horse trading is going to happen, but Georgia is certainly a state we’re going to be paying very close attention to.”

Collura stressed that Georgians seeking IVF or who own leftover embryos have the same rights as they did before Dobbs, but she’s worried that could change as early as next year.

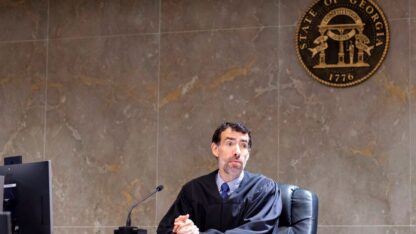

In his ruling overturning parts of the state’s 2019 abortion law, Fulton County Superior Court Judge Robert C. I. McBurney called the provisions “plainly unconstitutional” because they passed in 2019 and before the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Center ended the federal protection to abortion access.

“Under Dobbs, it may someday become the law of Georgia, but only after our Legislature determines in the sharp glare of public attention that will undoubtedly and properly attend such an important and consequential debate whether the rights of unborn children justify such a restriction on women’s right to bodily autonomy and privacy,” McBurney wrote in his ruling.

When it was passed, Georgia’s abortion law was one of the strictest in the country, but several states have since completely banned the procedure. In vitro advocates worry sending the issue back to the Legislature could result in a measure that would extend protections for unborn children in the womb to fertilized eggs in a freezer.

“Once you have a situation where state legislators are potentially regulating abortion, and then regulating embryos, it then impacts our community of people who are trying to build their family,” Collura said. “So we’re going to be watching Georgia very closely, and certainly have concerns about what could potentially happen, and we have to be ready.”

According to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, last month, a person with a hidden microphone asked Gov. Brian Kemp at a campaign stop whether he would support “a statewide ban on the destruction of embryos.”

In the leaked audio, Kemp said he liked the idea, but also noted the state’s abortion law passed with only one vote to spare. Kemp’s campaign said he would not support such a proposal.

Georgia Right to Life, an anti-abortion lobbying group, expresses mixed feelings on its position statement page.

“While GRTL empathizes with the many couples who turn to IVF as a treatment for infertility, we caution that some commonly used procedures surrounding this practice can cause the deaths of children at the embryonic stage. Any IVF procedure which leads to the destruction of human life at any level of development is opposed by GRTL.”

Dr. Valerie Libby is a fertility specialist at Shady Grove Fertility in Sandy Springs, one of the largest fertility clinics in the country. For her, a day in the office includes performing egg retrievals, intrauterine inseminations and embryo transfers, monitoring treatment response, as well as meeting with patients to discuss treatment plans. Lately, those conversations have included more questions about the future of state law.

“We assess the current legal environment and potential changes that may occur and educate our patients patients on the possibility of legislation changing,” she said. “Rarely, patients will choose to just not fertilize any eggs, so basically just store the eggs and the sperm separately until they’re ready to utilize those as embryos, and then they’ll fertilize just a few at a time to decrease the number of embryos that they have stored.”

It’s not clear whether a statewide ban on destroying embryos would prevent Georgia embryos from being discarded elsewhere.

“It’s a personal decision, and if they don’t feel comfortable discarding or donating their embryos to science or to other families that need embryos, then they have to continue to pay for embryo storage. If a patient wanted to discard their embryo and the law in Georgia did not allow for discarding embryos then we would explore other options including shipping embryos to clinics located in states where it was legal to do so,” Libby said.