Today, the Respect for Marriage Act got one step closer to becoming one of very few federal laws expressly protecting LGBTQ Americans. It’s expected to be signed into law by President Biden soon.

But even when it is signed, the legality of same-sex marriage will still rest on the 2015 Supreme Court case Obergefell v. Hodges, which found that same-sex marriage is constitutionally protected.

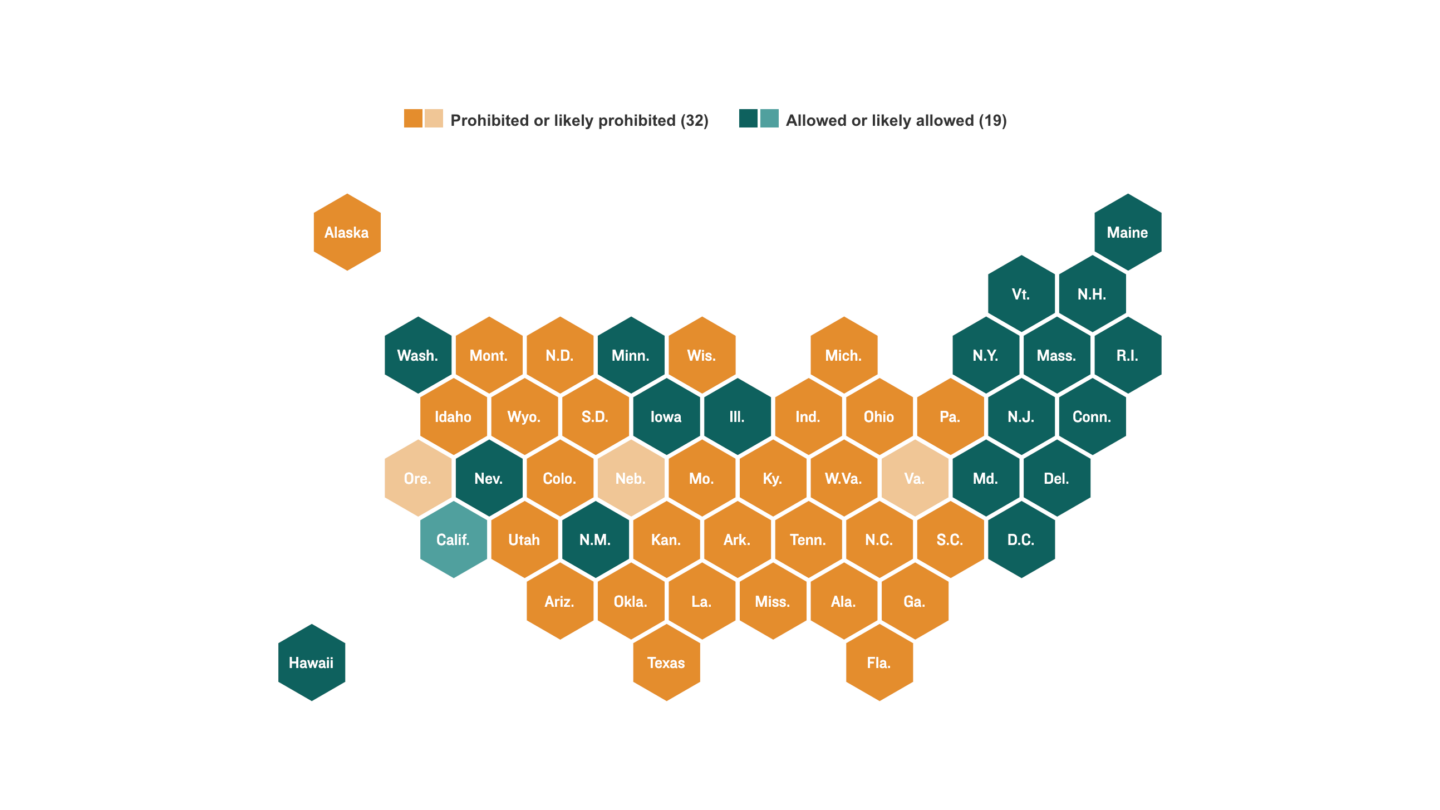

If the Court were to overturn Obergefell, the legality of same-sex marriages would revert to state law, and the majority of states would prohibit it. The Respect for Marriage Act wouldn’t change that, but it requires all states to recognize same-sex marriages performed in other states and federally recognizes these marriages.

The law unexpectedly gained Republican support and passed the Senate on Nov. 29 after being amended to ensure that nonprofit religious groups aren’t required to help perform same-sex marriages. It also repeals the Defense of Marriage Act, which prohibited the federal government from recognizing same-sex marriages and allowed states to refuse to recognize same-sex marriages performed elsewhere.

The specific impact of the Respect for Marriage Act on same-sex couples and their families in a post-Obergefell world would vary based on state law.

Why now?

The Respect for Marriage Act was introduced in the House to shore up marriage rights after the Supreme Court’s Dobbs v. Jackson decision, which overturned Roe v. Wade and called the stability of other landmark civil liberties cases into question.

Justice Clarence Thomas specifically called for the Court to reconsider Obergefell in his concurring Dobbs opinion because it rested in part on the same legal basis as Roe — substantive due process, which restricts government infringement upon fundamental individual rights even if they are unenumerated, such as birth control and interracial marriage.

“I want to be really clear that there would be no reason to reverse Obergefell and that it was correctly decided under existing precedents,” including the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, says Mary Bonauto, a senior attorney at GLBTQ Legal Advocates and Defenders who has argued landmark civil rights cases, including Obergefell. “But if it were, there is now a backstop in place requiring states to respect these marriages” and guaranteeing them federal recognition.

Jon Davidson, senior staff attorney for the American Civil Liberties Union’s LGBTQ & HIV Project and co-counsel on Obergefell, said the law is an “important advance” that will “make a lot of same-sex couples and their families feel more secure.”

However, he pointed out that the Respect for Marriage Act doesn’t address the ongoing violence against the LGBTQ community, from the Colorado Springs shooting to the high murder rate among transgender women of color, nor the wave of anti-transgender legislation in state legislatures.

“We’re seeing an all-out attack on the LGBTQ community, and this bill does nothing about any of that,” Davidson says. “It simply ensures that if a same-sex couple gets married, their marriage will be treated the same as other marriages.”

What’s next?

Advocates have been pushing for the Equality Act, a bill that would ban discrimination on the basis of sex, sexual orientation and gender identity and expand the definition of public accommodations. It passed the House in February 2021 but stalled in the Senate due to Republican opposition, in part because of tight restrictions on religious liberty exemptions.

The Respect for Marriage Act’s ability to garner bipartisan support was the result of the religious protections added by amendment.

Bonauto of the GLBTQ Legal Advocates and Defenders called the passage of the Respect for Marriage Act important and exciting even though the lack of Congressional support for non-discrimination legislation is bittersweet. “There’s a lot to do, but in the end, I think this was a valuable thing to do,” Bonauto says.