Congressman-elect Maxwell Frost was excited.

He thought that for the first few months of living in DC, he’d be couch surfing to save money. But as luck would have it, he found an apartment in Washington, D.C.’s Navy Yard neighborhood with monthly rent he figured he could swing.

This week, he went to view the apartment and spent about an hour filling out the application and providing information for a credit check. He also submitted a $50 application fee.

There was one thing he was worried about, though. After a year and half of campaigning (and winning, which, having been born in 1997, made him Congress’s first elected Generation Z lawmaker), Frost had gotten himself into debt. And, as a result, he had a low credit score.

Despite his low credit, Frost, said, the apartment representative said he’d be fine.

He wasn’t.

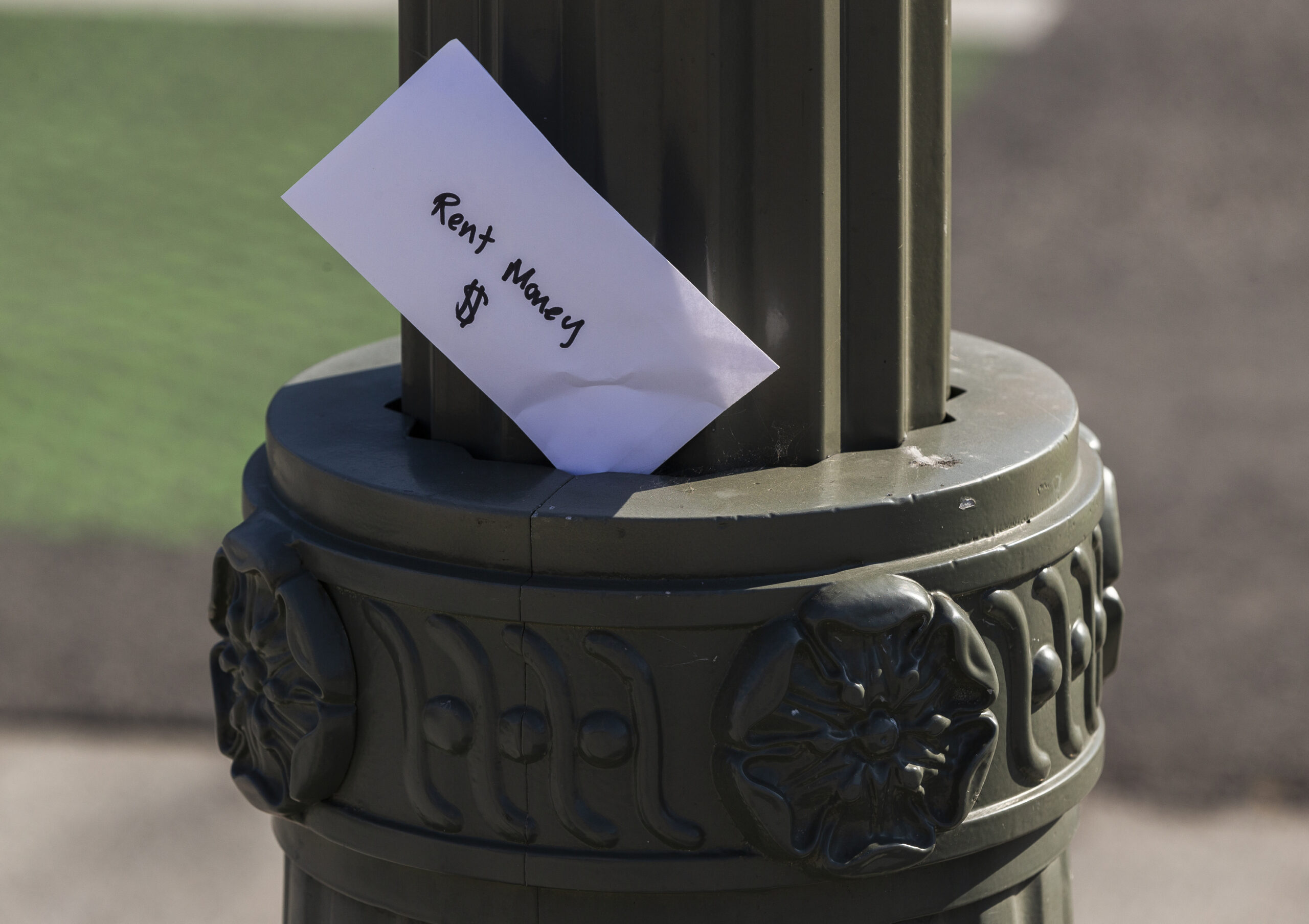

“Just applied to an apartment in DC where I told the guy that my credit was really bad. He said I’d be fine. Got denied, lost the apartment, and the application fee. This ain’t meant for people who don’t already have money,” Frost tweeted Thursday.

Landlords often use credit checks to approve a tenant’s rental application. But research has shown that credit scores actually perpetuate racial disparities. Sometimes the information provided in a credit check is even wrong, unfairly costing people an opportunity at housing, according to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Frost told NPR that he posted his tweet in a moment of frustration, but also to highlight this serious problem of affordability and accessibility in the D.C. political world for people who don’t come from wealth. While Frost dealt specifically with a credit rejection, other incoming lawmakers and politicians —especially younger members — have dealt with Washington’s lack of affordable housing in recent years.

“[Frost] just stating this publicly is kind of saying the quiet part out loud and shining a light on a reality that it’s incredibly expensive to live in D.C., to be young in D.C., and then maintain it even for members of Congress,” Casey Burgat, the legislative affairs program director at George Washington University.

This lack of affordability has a trickle-down effect, Burgat said.

“It makes Congress exactly what it’s been for so long: A disproportionately wealthy, disproportionately white institution,” Burgat said. “This is a main contributor for why people can’t afford to run for office. It’s not seen as a viable path. And though we’re getting a little bit better at our diversity, we still have a long way to go and the cost of it is not getting cheaper.”

Lawmakers have long struggled with D.C. housing

Zillow reports that, in Washington, D.C. the median rent is $2,600 — up $350 from last year’s average. The lack of affordable places to rent in major cities is a huge problem nationwide. Rental prices are up 15% from a year ago, Redfin reported in June.

Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez talked about her own trouble with affording housing when she was elected in 2018. She told The New York Times that year, “I have three months without a salary before I’m a member of Congress. So, how do I get an apartment? Those little things are very real.”

Frost said he’s spoken to other members of his freshmen class who similarly have had a hard time finding a place to live.

“It’s unfortunate. It’s a known issue, especially amongst the more working-class members,” he said. “It’s definitely a problem.”

Dozens of members of Congress have even turned their Capitol Hill offices into their makeshift apartments. This practice has been criticized as an inappropriate use of taxpayer money — and potentially uncomfortable for staffers who may catch their bosses in pajamas.

The financial load of campaigning is intimidating

On paper, being a politician pays incredibly well, Burgat said.

Rank-and-file members make a $174,ooo salary, though there are rules surrounding their investments and how much they can make.

But Burgat noted the election season is longer than it used to be, and that it makes it nearly impossible to have a regular full-time job.

For Frost’s part, he said he had to quit his full-time gig and take up Uber driving to make some money while he campaigned for a year and a half. Even that wasn’t enough to keep him out of debt, he said.

“There’s no career that supports this type of campaigning, particularly for young people,” Burgat said. “It’s for people that are able to withstand that financial burden for the amount of time that they have to, and just as we see with Congress itself, the people that are able to do that are disproportionately wealthy and disproportionately white.”

Frost noted he’s in a privileged place now that he is about to join Congress and will eventually make a good salary.

“In two years, my credit won’t necessarily be a huge problem. But, you know, right now it is, and so many people go through this,” he said.

His personal experience has encouraged him to look into solutions for other people in the same boat once he joins Congress in January.

“Bad credit alone shouldn’t mean that people have problems finding places to live,” he said.

Some of the things he’s hoping to tackle include pushing the federal government to invest in affordable housing in areas of opportunity and to end rental application fees.

“It’s known that a lot of these big leasing companies and management companies will tell people with bad credit that it’s okay to apply because these application fees for a lot of these companies are actually a source of revenue. And that should not be allowed,” Frost said.

Come January, Frost said he won’t be caught sleeping in his office.

“I think self preservation is important,” he said. “I think it’s important that we have spaces we can go to outside of work.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))