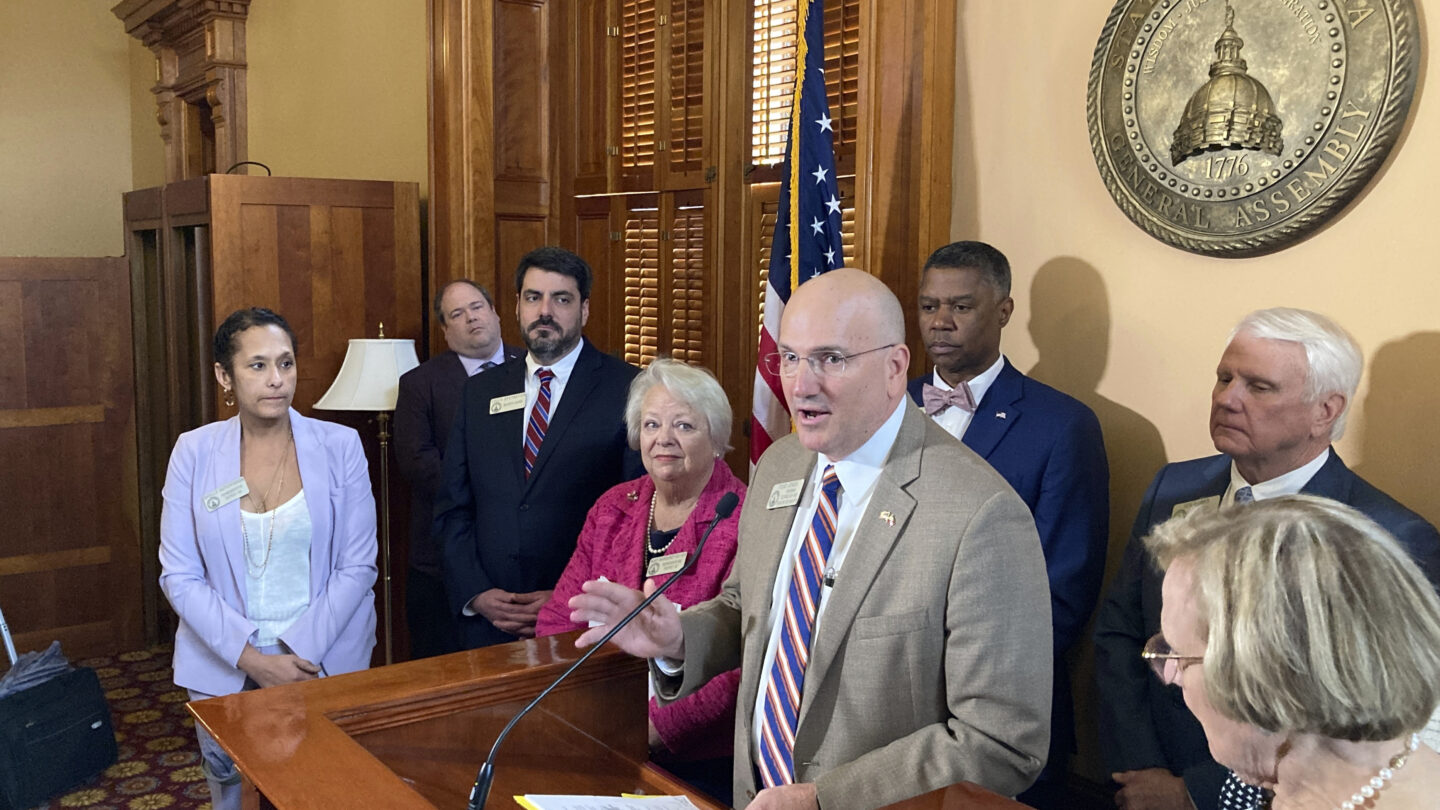

Georgia House Speaker Jon Burns said Tuesday that state lawmakers will make another push this year to improve mental health care, with a forthcoming bill outlining a series of changes, plus multiple studies aimed at setting the groundwork for more action in following years.

Under House Bill 520, the state would expand its student loan forgiveness program for mental health care providers, try to make it easier for officials to use a form of court-ordered outpatient treatment created last year. It also would create new crisis stabilization units in Columbus, Dublin and the Atlanta area, and mandate more data sharing among agencies to assist with studying problems and planning for services.

Burns, a Newington Republican, acknowledged that the effort comes in the wake of a major push in 2022 by then-House Speaker David Ralston, who died last year.

“While we miss him dearly we are proud to continue the work he inspired,” Burns said.

Last year’s measure pushed private insurers to abide by long-existing federal requirements to provide the same level of benefits for mental health disorders as they do for physical illness. It also required publicly funded insurance programs to spend more on patient care and authorized loan forgiveness. The law also allowed police officers to take someone they believe is in need of mental health treatment to an emergency facility for evaluation.

Funding for the state’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Disabilities was increased by $180 million.

But more money will be needed, sponsors of this year’s measure acknowledged, especially to increase how much Medicaid pays care providers, which in turn could allow care providers to raise wages for workers.

“I think we’re going to have relief in this budget,” said Mary Margaret Oliver, a Decatur Democrat.

One key initiative would be to study how treatment beds are currently distributed in Georgia, and whether enough beds exist to meet the state’s needs. Rep. Todd Jones, a Republican from Cumming, said people approach him frequently saying no treatment facility will take their loved one.

“There is not a week that goes by — and I can speak for representative Oliver and myself — when we literally have at least one or two Georgians contact us personally and say, ‘My son, my daughter, my cousin, what am I supposed to do? They can’t find a bed,’” Jones said.

One study will look at ways of addressing people who have mental illness and substance abuse issues, to try to keep them from cycling from jail to treatment to homelessness. Jones said that small population consumes a lot of state resources.

Oliver said that the part of last year’s law that created court-order assisted outpatient treatment doesn’t work well and makes it too hard to use. She said the law needs to be rewritten this year to make that option more useful.

Another study will look at lowering license barriers for mental health professionals, including those trained in other countries, and considering lowering or waiving experience requirements for people licensed in another state.

“We need our licensing boards for our mental health professionals to be more responsive, to be more efficient and more part of the modern world of online services and online payments,” Oliver said.