When Jimmy Carter stepped onto the national stage, he brought along those closest to him, introducing Americans to a colorful Georgia family that helped shape the 39th president’s public life and now, generations later, is rallying around him for the private final chapter of his 98 years.

“Family has always been important to Uncle Jimmy,” said Kim Fuller, whose father, Billy Carter, was the former president’s youngest brother and a favorite subject of national political reporters drawn to this family of Washington outsiders.

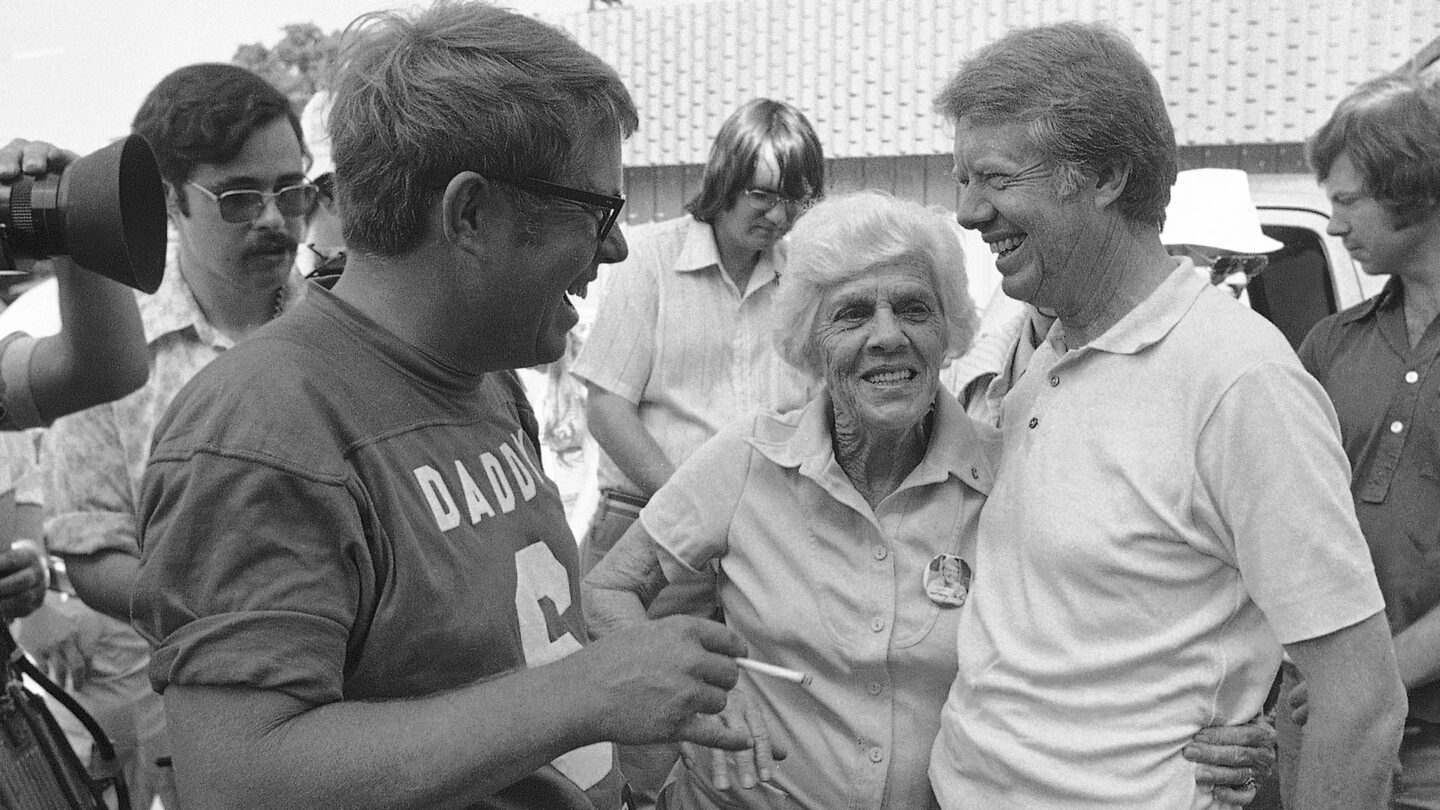

Carter has long outlived his nuclear family, including his mother, Lillian, and Billy, both of whom featured prominently in his political life — bringing charm, occasional scandal and even a forgotten brand of cheap brew: “Billy Beer.” The former president’s most constant political partner, wife Rosalynn, remains by his side as he receives end-of-life care at their home in Plains, Georgia, the tiny town where both were born.

Married since 1946 — longer than any other first couple — the Carters have four children and more than 20 grandchildren and great-grandchildren. Along with nieces, nephews and inlaws, it’s a sprawling extended family that has given Jimmy Carter a near-constant stream of visitors since he announced Feb. 18 that he would forgo further medical interventions and shift to hospice care at home.

“This is what I’ve known my entire life, what most of us have known,” said Fuller, who was school-aged when Carter was elected governor in 1970, then president in 1976. “I remember taking the train up to Atlanta to see them at the Governor’s Mansion.”

The Carters are not an establishment dynasty like the Republican Bushes or the Democratic Kennedys — whose scion Ted Kennedy was a Carter rival. But the family is critical to understanding the former president, from his methodical style to his outspoken Baptist faith.

When he launched his national campaign in 1974, it consisted mostly of the “Georgia mafia” — the name Washington would give his home-state advisers who came to the capital as outsiders — and his relatives. The peanut farmer-turned-politician added other Georgia supporters who traveled across the country campaigning.

Together they were “the Peanut Brigade,” and they set a new standard in presidential politics for retail campaigning in early primary states.

“Family members would disperse to different states and then they would all come back on Friday, go back through the questions they had gotten,” Minnesota Sen. Amy Klobuchar explained to the Associated Press in 2020, after she visited Carter as she sought the Democratic nomination.

As the candidate, Carter “would talk about how he would answer” voters so his stand-ins would be prepared for their next trips, Klobuchar said.

The Carters’ older sons were part of the crew. Their daughter, Amy, was seven when the campaign began; she remained mostly shielded other than being visible at public events with her parents. It was Carter’s mother and “baby brother,” 13 years his junior, who garnered headlines.

Lillian was a widow — Carter’s father, “Mr. Earl,” died in 1953 — who had turned over management of the family farm and peanut warehouse to Jimmy and Rosalynn. In her late 60s, Lillian applied for the Peace Corps and spent several years in India as her son made his climb to the Governor’s Mansion. After her return, Carter told her he planned to run for president.

“President of what?” she replied.

“She ran the family,” Fuller said. “Daddy and Uncle Jimmy may have acted like they did, but we all knew.”

That didn’t necessarily extend to Carter’s campaigns, of course. Whether candidate or executive, Carter was a famed micro-manager. Fuller mused, though, that he got it from his parents, exacting figures who had demanded much of Carter on the family farm.

Unlike Earl Carter, Lillian was a relative progressive even when Carter was a child. She “was impervious to criticism because of her independent spirit,” Carter wrote around his 90th birthday.

Tabbed “the most liberal woman in Georgia” by some journalists, she preferred topics other than politics. She declared White House life “boring” and flouted images of Baptist teetotaling.

“I know folks have a tizzy about it, but I like a little bourbon,” she said. “I’m a Christian, but that doesn’t mean I’m a long-faced square.'”

Billy Carter never seemed to find a comfortable place in his brother’s political operation.

“Daddy was perfectly happy at the gas station,” Kim Fuller said, gesturing across the street from her “Friends of Jimmy Carter” office festooned with 1976 posters and memorabilia.

Initially, that meant flaunting his “redneck power pick-up” to out-of-town reporters.

Amber Roessner, a University of Tennessee professor and expert on Carter’s campaigns, said some national media looked down on the Carters as rural Americans unworthy of the White House. Some reporters indulged their snobbery by covering Billy Carter while avoiding direct attacks on his brother, a Naval Academy graduate and engineer by training.

The younger Carter capitalized on his image with a deal for “Billy Beer.” News sources at the time reported that he got a $50,000 annual licensing fee from one brewer. That would be about $240,000 today, measured by consumer price index inflation. The president’s annual salary at the time was $200,000.

A beer deal, though, was mostly an eccentricity, like Lillian Carter’s quips.

More serious was the presidential sibling getting a $220,000 loan from the Libyan government, prompting one of several IRS and government inquiries of Carter’s activities as an apparent intermediary between American and Libyan oil interests. A Senate committee found that Billy Carter never influenced any American policy, effectively absolving the president of any wrongdoing. But the drama was another damaging blow ahead of Carter’s 1980 defeat.

After their return to Georgia, Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter built The Carter Center in Atlanta, staffed not by “the Peanut Brigade” but policy experts who advanced their international diplomatic and public health missions.

In Plains, they became the marquee members of Maranatha Baptist Church, teaching Sunday School to overflow crowds until recent health problems and the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lillian Carter died in 1983, less than three years after her son left the presidency. Billy Carter died in 1988.

While they’ve avoided dynastic trends, Jimmy Carter has passed down some of the family business. Eldest son Jack ran unsuccessfully for the U.S. Senate in Nevada in 2006. Grandson Jason served in the Georgia state Senate, as his grandfather did, and lost the 2014 governor’s race.

Jason Carter now chairs The Carter Center board — but only after his grandparents finally retired well into their 90s.

“He wanted to be able to see and experience the transition for The Carter Center to go on without him,” the younger Carter said in September, adding that he “would be shocked if I ever ran for office again.”

Billy’s daughter, meanwhile, inherited the church rostrum. She taught again Sunday, at one point emphasizing her uncle’s individual faith journey.

“Every breath he takes, he’s supposed to. Every step he takes, he’s supposed to,” she said. “And one day … he’s going to meet Christ, and he knows it. He knows it. And our hearts are heavy. But his isn’t. His heart’s not heavy.”