Georgia Medicaid insurer denied psychotherapy for thousands

A newspaper finds that the insurance company that manages medical care for many Georgia children has denied or partially denied more than 6,500 requests for psychotherapy between 2019 and mid-2022.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution reports that many of the requests denied by Amerigroup, a unit of insurance insurance giant Elevance Health, were for children in state-run foster care.

Child advocates tell the newspaper that the Department of Community Health, which is supposed to oversee the contract, isn’t holding Amerigroup accountable.

“The state is not doing its duty,” said Joe Sarra of the Georgia Advocacy Office, a federally mandated organization that works for people with disabilities.

In a January report to state lawmakers, the department said fewer than 100 psychotherapy requests were denied in calendar year 2019 and the 2021 and 2022 budget years by the state’s Medicaid managed care contractors, including Amerigroup.

But the newspaper found through documents obtained in open records requests that Amerigroup denied hundreds of authorization requests for psychiatric residential treatment, something the Department of Community Health didn’t include in its report to lawmakers. Amerigroup also denied thousands of requests for evaluations related to mental or behavioral health issues and hundreds of requests for autism-related services.

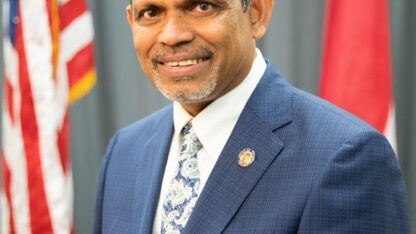

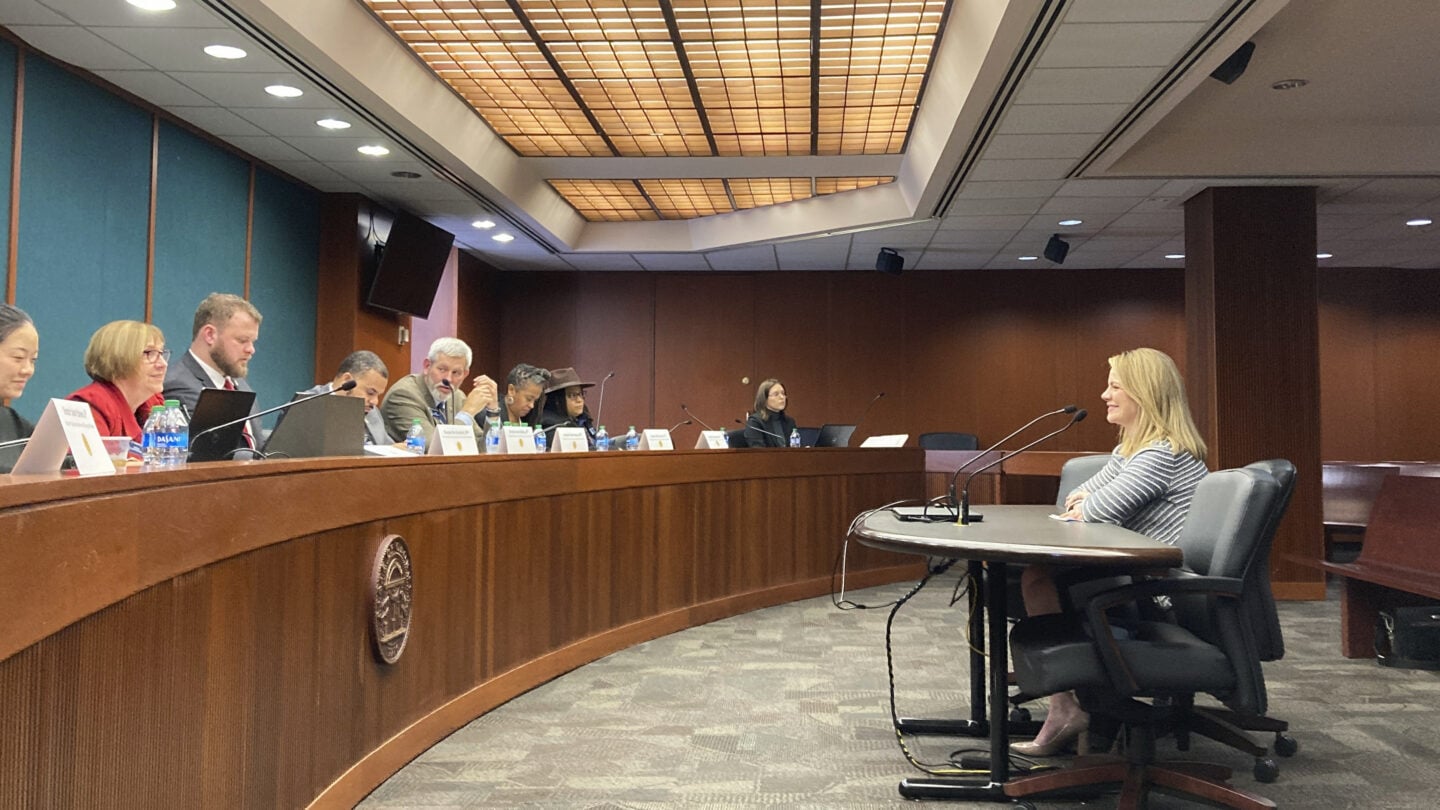

Melvin Lindsey, who leads Amerigroup in Georgia, has denied wrongdoing, telling lawmakers in a January hearing that children’s needs come before profits.

“I’ve never made a decision about how to treat anyone, particularly a foster care kid, that was related to cost and I never will,” Lindsey said. “We will get people the right services at the right time, all the time.”

But Human Services Commissioner Candice Broce, who also leads her department’s Division of Family & Children Services — the state’s foster care agency — has been sharply critical. She urged changes as the Department of Community Health seeks new bids on the Medicaid managed care contract that covers foster children. Broce wrote in a 2022 letter that children must wait weeks or months for an appointment, are rejected for services based on a narrow definition of “medical necessity” and are deprived of care coordination for their complex needs.

“To our knowledge, DCH has never levied financial penalties against Amerigroup for non-compliance with any of their contractual provisions,” Broce wrote.

In February, Department of Community Health spokesperson Fiona Roberts said that the contract bidding process precludes the department from commenting on denials and access to care. She said the department would prioritize behavioral health in new contracts.

Roberts said that its report didn’t match the Journal-Constitution’s reporting on denials because the newspaper looked at different categories and time-frames. She said the department has never fined Amerigroup for noncompliance, instead working with Amerigroup to resolve problems.

Email correspondence and denial letters from Amerigroup obtained by the Journal-Constitution show Amerigroup repeatedly denied services by citing a lack of records the insurer wanted to prove medical necessity. Children who were aggressive, hurting themselves or exhibiting other serious issues were frequently blocked from entering or staying longer at psychiatric residential treatment facilities. The insurer often rejected such expensive stays with the same language citing a lack of medical necessity, frequently saying, “Records no longer show you have these issues.”

Among children denied entrance to residential treatment: an 11-year-old girl who smeared feces in the bathroom of a foster care home and attempted to jump out of a window hours after being released from a psychiatric unit. Amerigroup approved a residential stay months later after the girl tried to both drown and electrocute herself, according to the state’s foster care agency. At that point, no facility would accept her.

Amerigroup also denied a medical provider’s request for a residential treatment of a 13-year-old foster child who was trying to hurt herself and was aggressive toward others. While the state appealed the company’s decision, she tried to overdose on lithium pills and cut herself with glass.

The division has created a team of lawyers to appeal coverage denials, and Broce said in January that the division has never lost an appeal. In the meantime, Broce said the division advanced $57 million last year to cover treatment Amerigroup denied.

“This is a problem that far exceeds foster care,” said Melissa Carter, executive director of the Barton Child Law and Policy Center at Emory University.

“The fact of the matter is, many of those children who are currently in foster care may not need to be if parents were able to access services to meet their children’s needs in the community.”