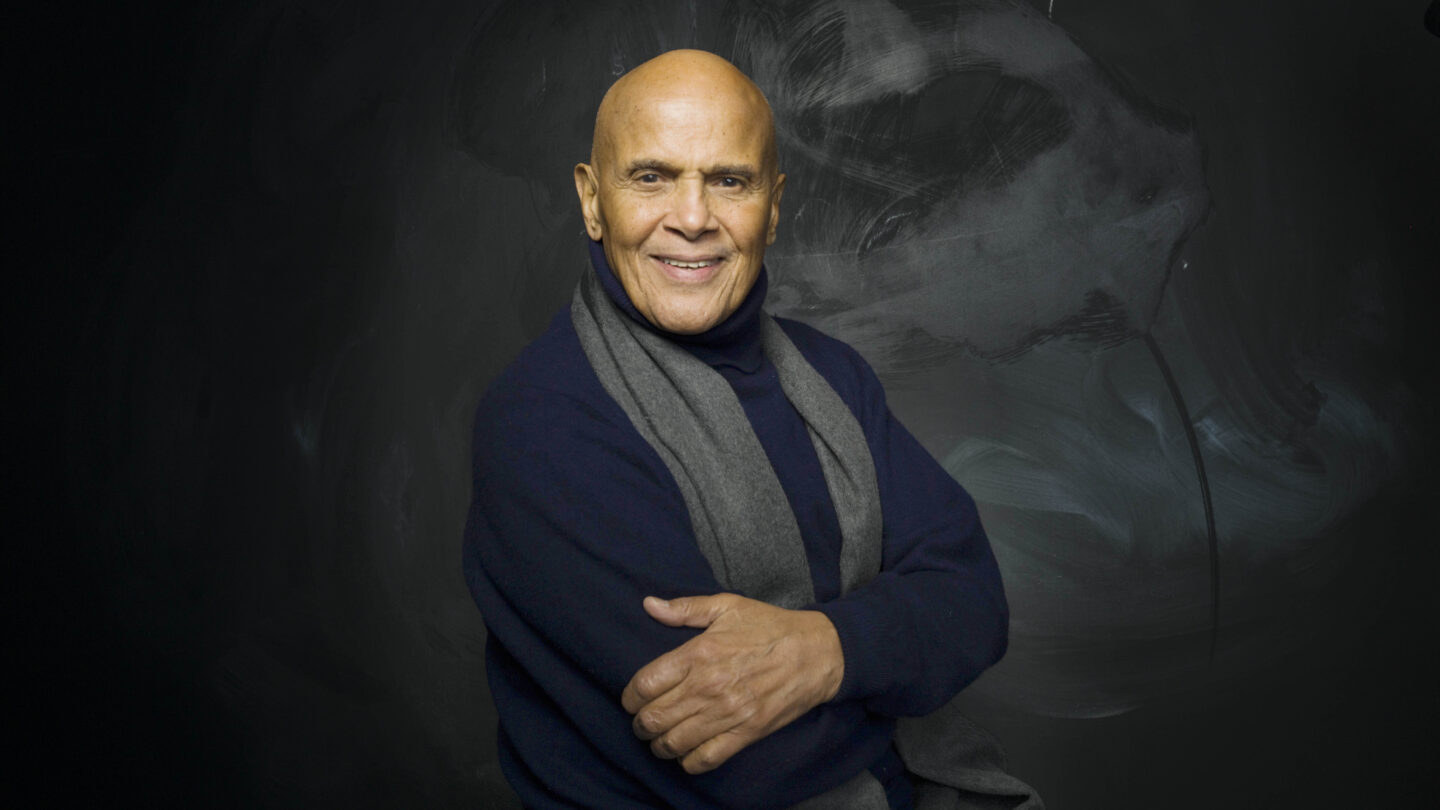

Belafonte’s friend, Civil Rights leader Andrew Young, would note that Belafonte was the rare person to grow more radical with age. He was ever engaged and unyielding, willing to take on Southern segregationists, Northern liberals, the billionaire Koch brothers and the country’s first Black president, Barack Obama, whom Belafonte would remember asking to cut him “some slack.”

Belafonte responded, “What makes you think that’s not what I’ve been doing?”

Belafonte had been a major artist since the 1950s. He won a Tony Award in 1954 for his starring role in John Murray Anderson’s “Almanac” and five years later became the first Black performer to win an Emmy for the TV special “Tonight with Harry Belafonte.”

In 1954, he co-starred with Dorothy Dandridge in the Otto Preminger-directed musical “Carmen Jones,” a popular breakthrough for an all-Black cast. The 1957 movie “Island in the Sun” was banned in several Southern cities, where theater owners were threatened by the Ku Klux Klan because of the film’s interracial romance between Belafonte and Joan Fontaine.

His “Calypso,” released in 1955, became the first officially certified million-selling album by a solo performer, and started a national infatuation with Caribbean rhythms (Belafonte was nicknamed, reluctantly, the “King of Calypso”). Admirers of Belafonte included a young Bob Dylan, who debuted on record in the early ’60s by playing harmonica on Belafonte’s “Midnight Special.”

“Harry was the best balladeer in the land and everybody knew it,” Dylan later wrote. “He was a fantastic artist, sang about lovers and slaves — chain gang workers, saints and sinners and children. … Harry was that rare type of character that radiates greatness, and you hope that some of it rubs off on you.”

Belafonte befriended King in the spring of 1956 after the young Civil Rights leader called and asked for a meeting. They spoke for hours, and Belafonte would remember feeling King raised him to the “higher plane of social protest.” Then at the peak of his singing career, Belafonte was soon producing a benefit concert for the bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama that helped make King a national figure. By the early 1960s, he had decided to make Civil Rights his priority.

“I was having almost daily talks with Martin,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir “My Song,” published in 2011. “I realized that the movement was more important than anything else.”

The Kennedys were among the first politicians to seek his opinions, which he willingly shared. John F. Kennedy, at a time when Blacks were as likely to vote for Republicans as for Democrats, was so anxious for his support that during the 1960 election he visited Belafonte at his Manhattan home. Belafonte explained King’s importance and arranged for King and Kennedy to meet.

“I was quite taken by the fact that he (Kennedy) knew so little about the Black community,” Belafonte told NBC in 2013. “He knew the headlines of the day, but he wasn’t really anywhere nuanced or detailed on the depth of Black anguish or what our struggle’s really about.”

Belafonte would often criticize the Kennedys for their reluctance to challenge the Southern segregationists who were then a substantial part of the Democratic Party. He argued with Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, the president’s brother, over the government’s failure to protect the “Freedom Riders” trying to integrate bus stations. He was among the Black activists at a widely publicized meeting with the attorney general, when playwright Lorraine Hansberry and others stunned Kennedy by questioning whether the country even deserved Black allegiance.

“Bobby turned red at that. I had never seen him so shaken,” Belafonte later wrote.

In 1963, Belafonte was deeply involved with the historic March on Washington. He recruited his close friend Sidney Poitier, Paul Newman and other celebrities and persuaded the left-wing Marlon Brando to co-chair the Hollywood delegation with the more conservative Charlton Heston, a pairing designed to appeal to the broadest possible audience. In 1964, he and Poitier personally delivered tens of thousands of dollar to activists in Mississippi after three “Freedom Summer” volunteers were murdered — the two celebrities were chased by car at one point by members of the KKK. The following year, he brought in Tony Bennett, Joan Baez and other singers to perform for the marchers in Selma, Alabama.

When King was assassinated, in 1968, Belafonte helped pick out the suit he was buried in, sat next to his widow, Coretta, at the funeral, and continued to support his family, in part through an insurance policy he had taken out on King in his lifetime.

“Much of my political outlook was already in place when I encountered Dr. King,” Belafonte later wrote. “I was well on my way and utterly committed to the Civil Rights struggle. I came to him with expectations and he affirmed them.”

King’s death left Belafonte isolated from the Civil Rights community. He was turned off by the separatist beliefs of Stokely Carmichael and other “Black Power” activists and had little chemistry with King’s designated successor, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy. But the entertainer’s causes extended well beyond the U.S.

He mentored South African singer and activist Miriam Makeba and helped introduce her to American audiences, the two winning a Grammy in 1964 for the concert record “An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba.” He coordinated Nelson Mandela’s first visit to the U.S. since being released from prison in 1990. A few years earlier, he had initiated the all-star, million-selling “We Are the World” recording, the Grammy-winning charity song for famine relief in Africa.

Belafonte’s early life and career paralleled those of Poitier, who died in 2022. Both spent part of their childhoods in the Caribbean and ended up in New York. Both served in the military during World War II, acted in the American Negro Theatre and then broke into film. Poitier shared his belief in Civil rights, but still dedicated much of his time to acting, a source of some tension between them. While Poitier had a sustained and historic run in the 1960s as a leading man and box office success, Belafonte grew tired of acting and turned down parts he regarded as “neutered.”

“Sidney radiated a truly saintly dignity and calm. Not me,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir. “I didn’t want to tone down my sexuality, either. Sidney did that in every role he took.”

Belafonte was very much a human being. He acknowledged extra-marital affairs, negligence as a parent and a frightening temper, driven by lifelong insecurity. “Woe to the musician who missed his cue, or the agent who fouled up a booking,” he confided.

In his memoir, he chastised Poitier for a “radical breach” by backing out on a commitment to star as Mandela in a TV miniseries Belafonte had conceived, then agreeing to play Mandela for a rival production. He became so estranged from King’s widow and children that he was not asked to speak at her funeral. In 2013, he sued three of King’s children over control of some of the Civil rights leader’s personal papers.

In his memoir, he would allege that the King children were more interested in “selling trinkets and memorabilia” than in serious thought.

He made news years earlier when he compared Colin Powell, the first Black secretary of state, to a slave “permitted to come into the house of the master” for his service in the George W. Bush administration.

He was in Washington in January 2009 as Obama was inaugurated, officiating along with Baez and others at a gala called the Inaugural Peace Ball. But Belafonte would later criticize Obama for failing to live up to his promise and lacking “fundamental empathy with the dispossessed, be they white or Black.”

Belafonte did occasionally serve in government, as cultural adviser for the Peace Corps during the Kennedy administration and decades later as goodwill ambassador for UNICEF. For his film and music career, he received the motion picture academy’s Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award, a National Medal of Arts, a Grammy for lifetime achievement and numerous other honorary prizes. He found special pleasure in winning a New York Film Critics Award in 1996 for his work as a gangster in Robert Altman’s “Kansas City.”

“I’m as proud of that film critics’ award as I am of all my gold records,” he wrote in his memoir.

He was married three times, most recently to photographer Pamela Frank, and had four children. Three of them — Shari, David and Gina — became actors. He is also survived by two stepchildren and eight grandchildren.

Harry Belafonte was born Harold George Bellanfanti Jr. in 1927, in a community of West Indians in Harlem. His father was a seaman and cook with Dutch and Jamaican ancestry and his mother, part Scottish, worked as a domestic. Both parents were undocumented immigrants and Belafonte recalled living “an underground life, as criminals of a sort, on the run.”

The household was violent: Belafonte sustained brutal beatings from his father, and he was sent to live for several years with relatives in Jamaica. Belafonte was a poor reader — he was probably dyslexic, he later realized — and dropped out of high school, soon joining the Navy. While in the service, he read “Color and Democracy” by the Black scholar W.E.B. Du Bois and was deeply affected, calling it the start of his political education.

After the war, he found a job in New York as an assistant janitor for some apartment buildings. One tenant liked him enough to give him free tickets to a play at the American Negro Theatre, a community repertory for black performers. Belafonte was so impressed that he joined as a volunteer, then as an actor. Poitier was a peer, both of them “skinny, brooding and vulnerable within our hard shells of self-protection,” Belafonte later wrote.

Belafonte met Brando, Walter Matthau and other future stars while taking acting classes at the New School for Social Research. Brando was an inspiration as an actor, and he and Belafonte became close, sometimes riding on Brando’s motorcycle or double dating or playing congas together at parties. Over the years, Belafonte’s political and artistic lives would lead to friendships with everyone from Frank Sinatra and Lester Young to Eleanor Roosevelt and Fidel Castro.

His early stage credits included “Days of Our Youth” and Sean O’Casey’s “Juno and the Peacock,” a play Belafonte remembered less because of his own performance than because of a backstage visitor, Robeson, the actor, singer and activist.

“What I remember more than anything Robeson said, was the love he radiated, and the profound responsibility he felt, as an actor, to use his platform as a bully pulpit,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir. His friendship with Robeson and support for left-wing causes eventually brought trouble from the government. FBI agents visited him at home and allegations of Communism nearly cost him an appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show.” Leftists suspected, and Belafonte emphatically denied, that he had named names of suspected Communists so he could perform on Sullivan’s show.

By the 1950s, Belafonte was also singing, finding gigs at the Blue Note, the Vanguard and other clubs — he was backed for one performance by Charlie Parker and Max Roach — and becoming immersed in folk, blues, jazz and the calypso he had heard while living in Jamaica. Starting in 1954, he released such top 10 albums as “Mark Twain and Other Folk Favorites” and “Belafonte,” and his popular singles included “Mathilda,” “Jamaica Farewell” and “The Banana Boat Song,” a reworked Caribbean ballad that was a late addition to his “Calypso” record.

“We found ourselves one or two songs short, so we threw in `Day-O’ as filler,” Belafonte wrote in his memoir.

He was a superstar, but one criticized, and occasionally sued, for taking traditional material and not sharing the profits. Belafonte expressed regret and also worried about being typecast as a calypso singer, declining for years to sing “Day-O” live after he gave television performances against banana boat backdrops.

Belafonte was the rare young artist to think about the business side of show business. He started one of the first all-Black music publishing companies. He produced plays, movies and TV shows, including Off-Broadway’s “To Be Young, Gifted, and Black,” in 1969. He was the first Black person to produce for TV.

Belafonte made history in 1968 by filling in for Johnny Carson on the “Tonight” show for a full week. Later that year, a simple, spontaneous gesture led to another milestone. Appearing on a taped TV special starring Petula Clark, Belafonte joined the British singer on the anti-war song “On the Path of Glory.” At one point, Clark placed a hand on Belafonte’s arm. The show’s sponsor, Chrysler, demanded the segment be reshot. Clark and Belafonte resisted, successfully, and for the first time a white woman touched a Black man’s arm on primetime television.

In the 1970s, he returned to movie acting, co-starring with Poitier in “Buck and the Preacher,” a commercial flop, the raucous and popular comedy “Uptown Saturday Night.” His other film credits include “Bobby,” “White Man’s Burden,” and cameos in Altman’s “The Player” and “Ready to Wear.” He also appeared in the Altman-directed TV series “Tanner on Tanner” and was among those interviewed for “When the Levees Broke,” Spike Lee’s HBO documentary about Hurricane Katrina. In 2011, HBO aired a documentary about Belafonte, “Sing Your Song.”

Mindful to the end that he grew up in poverty, Belafonte did not think of himself as an artist who became an activist, but an activist who happened to be an artist.

“When you grow up, son,” Belafonte remembered his mother telling him, “never go to bed at night knowing that there was something you could have done during the day to strike a blow against injustice and you didn’t do it.”

Former Associated Press writer Mike Stewart contributed to this report.