The U.S. is seeing high levels of heat-related illness this year, according to data the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provided to NPR.

The agency has been collecting national data on heat-related illness from emergency departments since 2018 and currently releases it daily through its Heat & Health Tracker.

The data serves as an early-warning system for communities suffering from the heat. “It’s providing real-time health information,” says Claudia Brown, a health scientist with the CDC’s Climate and Health Program.

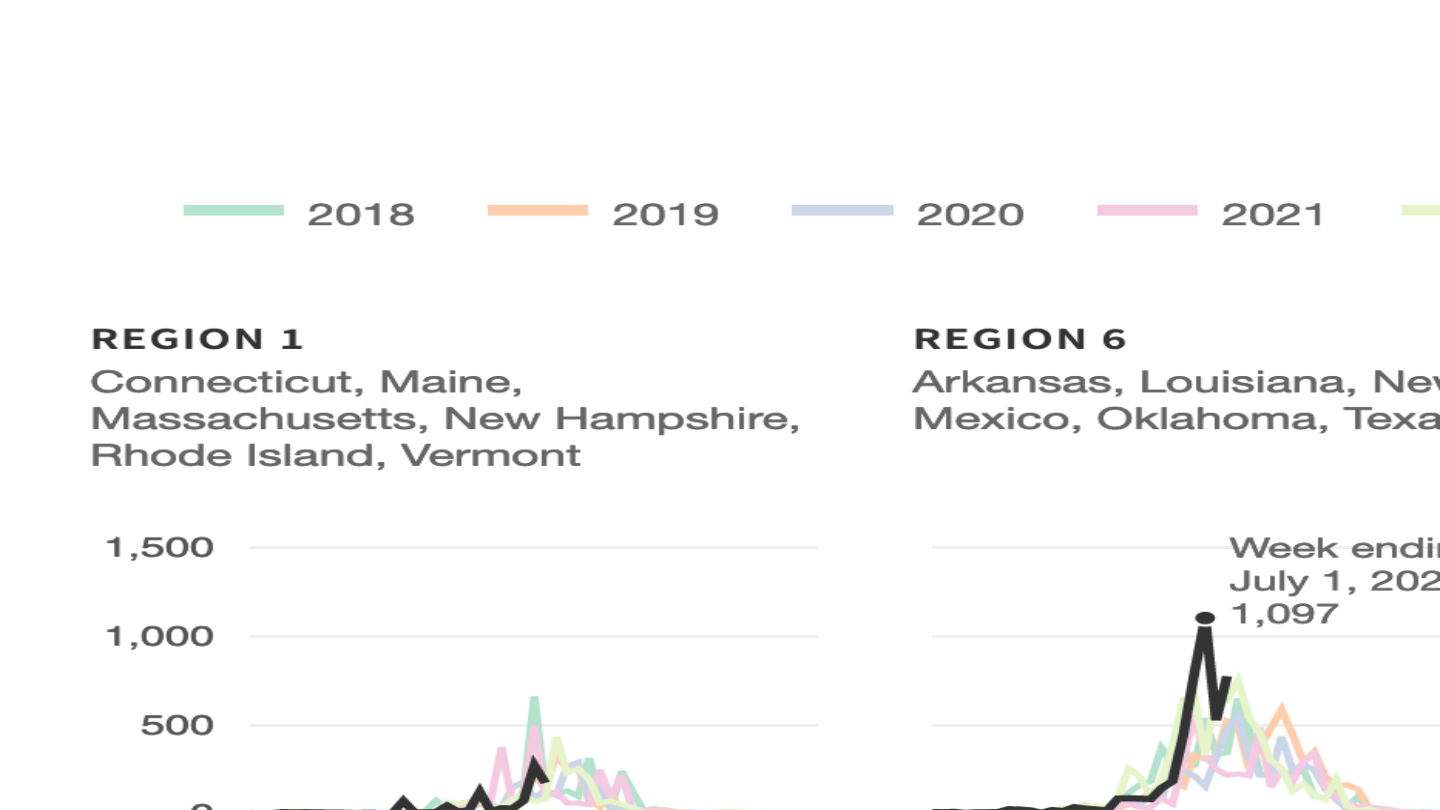

The agency provided NPR with historical data and an analysis of 2023’s trends to date. The historic data is limited to places that have reported regularly so that rates that can be compared over time. Explore trends in your region and see when rates of illness have spiked.

The CDC collects this data through its National Syndromic Surveillance Program, which takes in anonymized information from electronic health records shared by participating medical facilities. About 75% of the nation’s emergency departments report into the program.

Some recent spikes in heat-related illness

This summer, hospitals recorded a large spike in heat-related illness in the region that includes Texas as well as Arkansas, Louisiana, New Mexico and Oklahoma. According to the CDC analysis, for several days in June, the rates of emergency department visits for heat-related illness were the highest seen in this region in the past five years.

Parts of the region saw above-average temperatures last month. According to the Texas Tribune, a mid-month heat wave brought “an unusually high number of 100-degree days.”

Record high rates of heat-related illness showed up early in the year in several other regions. Federal health regions 1, 2, 5 and 8, which includes the Northeast, the upper Midwest and the Rocky Mountain region, saw the highest daily rates of heat-related illness recorded in any April over the past five years.

And region 10, which includes the Pacific Northwest and Idaho, saw the same trend of record-setting daily heat-related hospital visits for the months of both April and May.

In 2021, that region also saw the highest recorded rate of heat-related illness in any region since 2018, when much higher-than-average temperatures scorched a region that doesn’t traditionally deal with heat, and where air conditioning use isn’t widespread.

“There’s a lot of regional variation in what temperatures trigger a heat-related illness spike, based on what people are acclimated to, what their infrastructure is built for,” Brown says.

Heat-related deaths are rising

CDC’s Brown notes that extreme summer heat is increasing in the U.S. “It’s hot again, and it’s getting hotter every summer,” she says. “Climate projections indicate that extreme heat events will be more frequent and intense in coming decades as well.”

And she says, despite some improvements in forecasting, public messaging and access to air conditioning, “extreme heat events remain a cause of preventable deaths nationwide.”

She cites the increase in heat-related deaths in 2020, 2021 and 2022, as tracked by the National Center for Health Statistics.

The CDC warns that anyone spending time in the heat should take precautions. Heat-related illness may start as a rash, headache, dizziness or nausea, but can quickly escalate.

Heat stroke, or hyperthermia, happens when the body loses the ability to regulate temperature. While it often develops as a bad turn from heat cramps or heat exhaustion, “it can also strike suddenly, without prior symptoms,” Brown says.

Those with heat stroke might feel confused or dizzy, and may or may not be sweating. If someone feels these symptoms or suspects heat stroke for any reason, Brown advises you call 911 immediately.

Those who are more vulnerable to heat-related illness include pregnant people, those with lung conditions, young children and the elderly. Outdoor labor and sports can contribute. For instance, in Austin, Texas, a large share of their emergency visits are coming from young men overexerting themselves in the heat, according to CBS Austin.

Living in cities surrounded by pavement and little shade also increases the ambient heat levels.

The CDC is working with cities on preparing for more extreme weather, expected to get worse in the coming decades due to climate change. They hope that better planning and public awareness, as well as more air conditioning, can help protect people from the consequences of heat.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))