Lawyer: ‘Stocking Strangler’ Inmate Should Not Be Executed

Death-row inmate Carlton Gary was convicted in 1986 on three counts each of malice murder, rape and burglary for crimes committed in 1977.

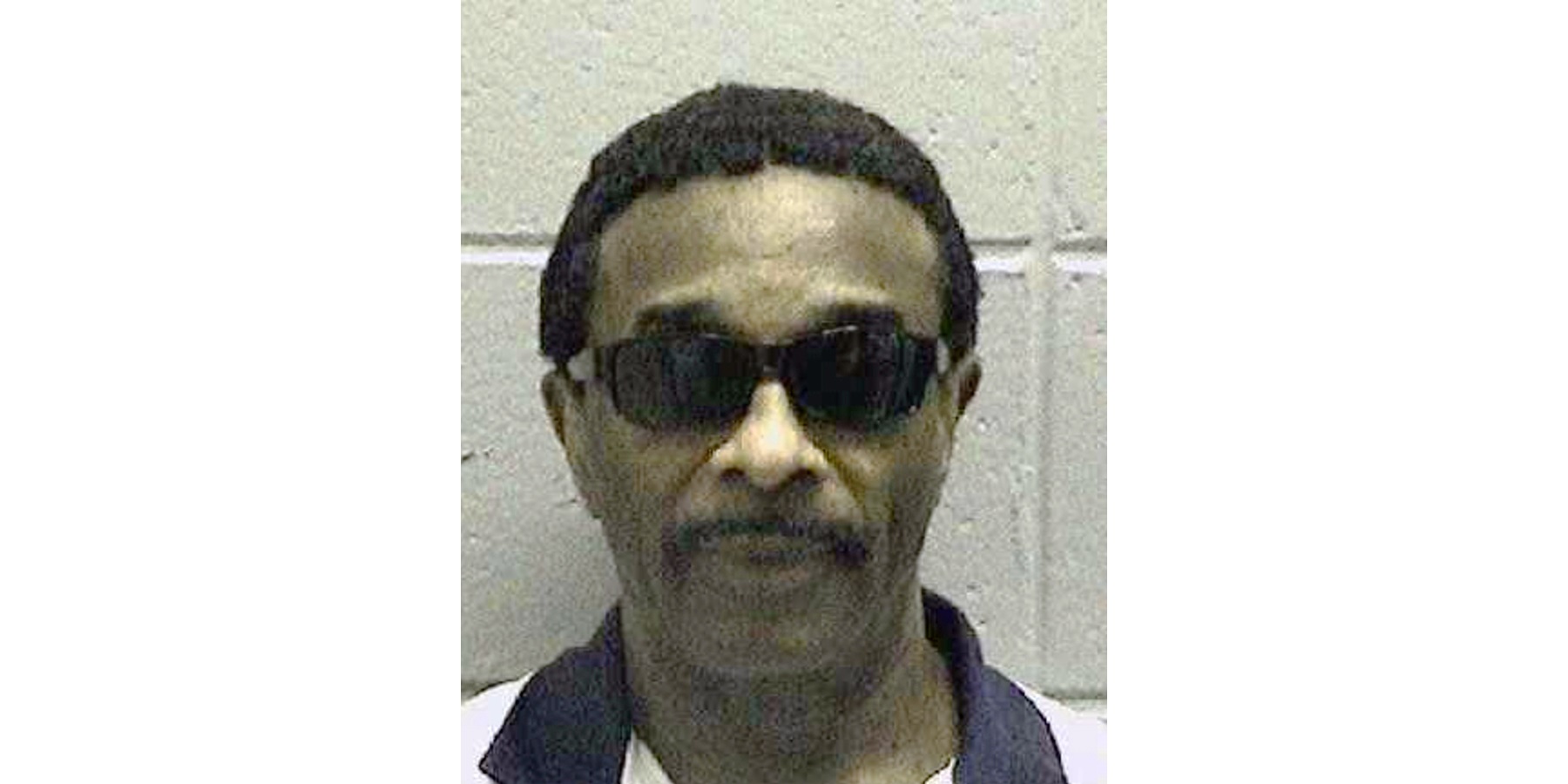

Georgia Department of Corrections via AP

A lawyer for a Georgia inmate known as the “stocking strangler” says newly discovered evidence proves his client’s innocence, and his scheduled execution this week would be a “stain on the State of Georgia.”

Carlton Gary, 67, is scheduled to be put to death Thursday evening at the state prison in Jackson in what would be Georgia’s first execution this year. He was convicted in 1986 on three counts each of malice murder, rape and burglary for the 1977 deaths of 89-year-old Florence Scheible, 69-year-old Martha Thurmond and 74-year-old Kathleen Woodruff.

The west Georgia city of Columbus was terrified by a string of attacks on older women between September 1977 and April 1978. Ranging in age from 59 to 89, the women were beaten, raped and choked, often with their own stockings. Seven died and two were injured.

Lawyers for the state have long maintained Gary was behind all nine attacks, along with some similar attacks in New York state. At trial, the prosecution introducted evidence from all the attacks to establish a pattern.

Gary’s attorneys asked the State Board of Pardons and Paroles at a closed-door hearing Wednesday to spare his life. The parole board is the only authority in Georgia with power to commute a death sentence.

Gary also has appeals pending before the Georgia Supreme Court and the U.S. Supreme Court.

Gary’s lawyers have argued physical evidence that exonerates him wasn’t available at the time of trial, either because the necessary testing wasn’t yet available or because the state didn’t provide it. His trial attorney was also hobbled by a lack of resources for experts or investigators, they say.

Barring a stay, “a person who never got a fair trial and whose guilt has been seriously questioned by hard physical and scientific evidence suppressed by the State and not revealed until long after trial will be executed,” attorney Jack Martin said in a statement. “That execution will be a stain on the State of Georgia, the judiciary and the Parole Board.”

Lawyers for the state say the evidence Gary’s lawyers present as new has already been considered by the courts and deemed insufficient and unlikely to have changed the trial outcome.

His “convictions and sentences have been exhaustively reviewed for the past 30 years in both state and federal court and found to be constitutionally sound,” state lawyers wrote in a filing with the U.S. Supreme Court.

Key evidence that could potentially have proven that Gary was not the stocking strangler includes slides with semen found on Thurmond’s body and Scheible’s sheets, his lawyers argue. Bodily fluid testing done on those samples likely excludes Gary as the attacker, they say, and DNA testing could have confirmed that. But that testing couldn’t be done because the samples were contaminated at a state crime lab.

DNA evidence found on clothing taken from the home of a victim who survived an attack and dramatically identified Gary at trial did not match his DNA, his lawyers wrote. Additionally, they say, bite mark and fingerprint evidence relied upon by the prosecution was problematic and a shoeprint found at one of the crime scenes doesn’t match with Gary.

State lawyers acknowledge that the evidence from the Thurmond and Scheible crime scenes was contaminated in a state lab, but they say there’s no evidence that was done in bad faith. And there’s no proof that the woman who identified Gary in court was wearing the clothing that had DNA other than Gary’s at the time of the attack, they say. The other evidence his lawyers claim exonerates him is largely based on dueling expert testimony, state lawyers say.

Further, they say, DNA evidence has surfaced that positively matches Gary to one of the attacks for which he wasn’t charged. He also has been linked to nearly identical attacks in Georgia and New York and he admitted to being at the crime scenes in both states but blamed the rapes and killings on others, claims that were never corroborated, they say.

Gary’s lawyers have asked the U.S. Supreme Court to consider whether the Eighth and Fourteenth amendments of the U.S. Constitution prohibit the execution of someone who is innocent if the evidence of innocence wasn’t available at the time of trial. They also are asking the court to weigh whether the destruction of possibly exculpatory evidence by the state violates those same constitutional rights. Finally, they ask if the death penalty itself is unconstitutional because of “an unacceptable risk of executing the innocent.”