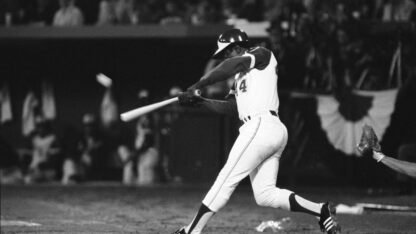

Hank Aaron refused to be intimidated by racist hate mail or threats during his pursuit of Babe Ruth’s home run record.

Aaron’s teammates, including Dusty Baker, worried on his behalf even as the future Hall of Famer circled the bases following his record-breaking 715th homer on April 8, 1974. Baker, who was on deck, and Tom House, who caught the homer in the Atlanta bullpen behind the left-field wall, will return Monday for the 50-year anniversary of the homer.

After sprinting from the bullpen to deliver the ball to Aaron at home plate, House found Aaron’s mother giving the slugger a big hug.

“You could see both of them with tears in their eyes,” House told The Associated Press. “… It was a mother and son. Obviously, that was cool. It was also mom protecting her boy from at that time everybody thought somebody would actually try to shoot him at home plate.

“So there were all kind of things. I gave him the ball. I said, ‘Here it is, Hank.’ He said ‘Thanks, kid.’”

Baker referred to Aaron as a father figure or big brother who looked out for him as he began his playing career with the Braves. Baker and other teammates, including Ralph Garr, tried to look out for Aaron during the home run chase.

“We always felt the need to protect him, always felt that need,” Baker said last week. “I think we were more afraid for him than he was actually afraid because he never showed any fear of the threats or whatever. It seems like it drove him to a higher concentration level than ever before was possible.”

Baker retired as Houston’s manager following the 2023 season.

Bob Hope, then the Braves media relations director, said Aaron would not be deterred by the threats issued late in the 1973 season as he approached Ruth’s record of 714 career homers.

“One time the FBI wanted to come meet with him on a Sunday and asked him not to play because they felt they had legitimate death threats on him,” Hope said.

“We went down to the clubhouse and sat down with him and Hank just said: ‘What kind of statement would that be? I am a baseball player. You guys do what you need to do to keep things secure, but I’m playing baseball.’ And I thought that was very reflective of his personality all the way through.”

Hope said most fan mail Aaron received was positive. “The hate mail was not pleasant, but there wasn’t nearly as much as you’re led to believe,” Hope said. “It was just a very, very small percentage of the fans were causing that problem.”

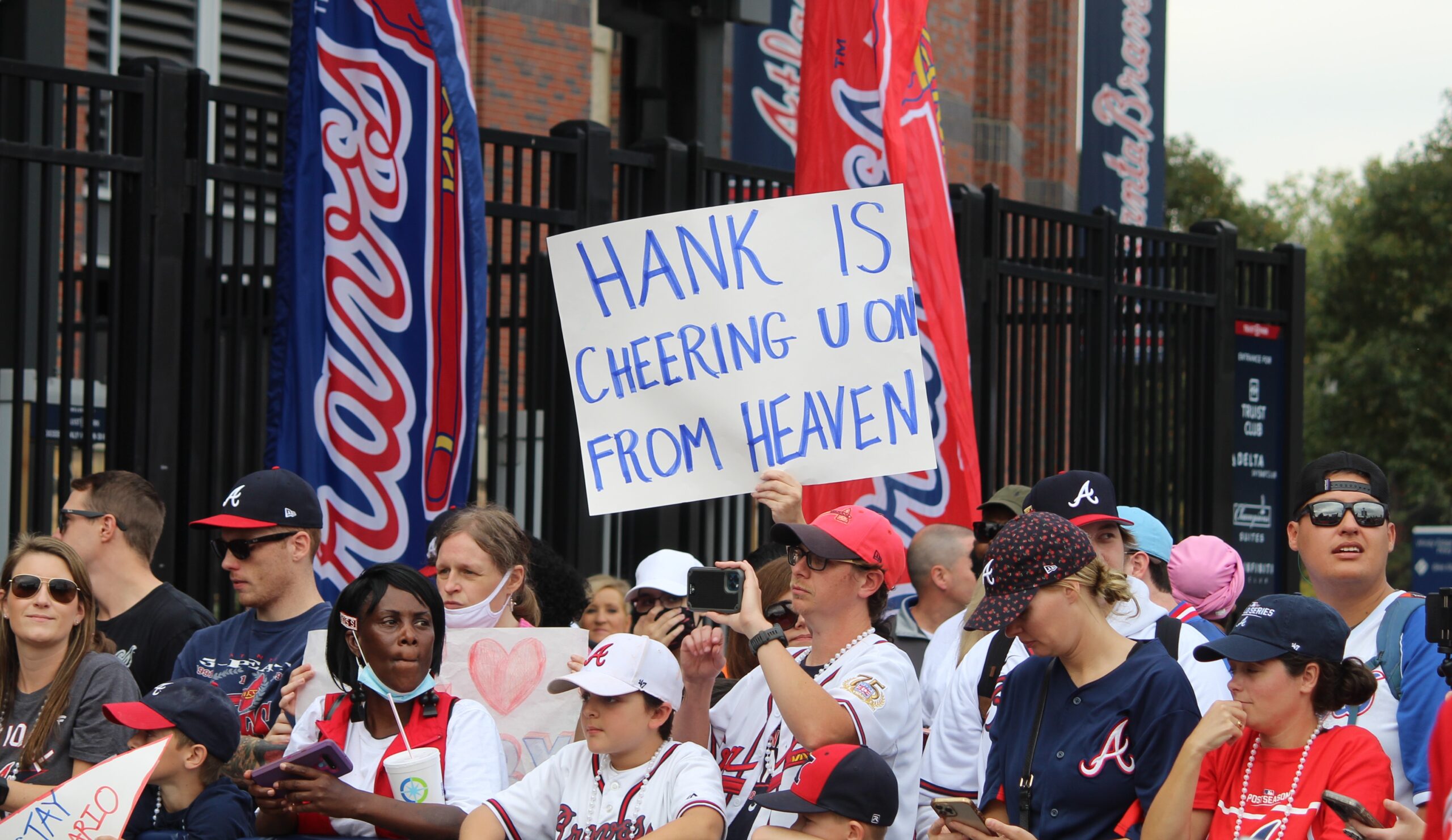

Hope and Baker remained close to Aaron after Aaron’s career and until his death in 2021 at 86.

“One of the honors of your life that you don’t want is when Hank died, at his funeral, Dusty and I were the only two nonfamily pallbearers,” Hope said. “When I realized that at the funeral, it was almost overwhelming.”

Wonya Lucas, Aaron’s niece and the daughter of Bill Lucas, who with the Braves in 1976 became Major League Baseball’s first African American general manager, said she can remember “Uncle Hank” remaining strong during the chase. She said that stayed constant even when threats led to police cars showing up at Aaron’s home and Aaron’s oldest daughter, Gaile, having to return home from college.

“I certainly understood the gravity of the situation and how the mood shifted is probably a good way to put it,” Wonya Lucas said Friday. “But I do also remember his quiet strength, and despite all those conditions I described I felt safe in the home because I felt he gave us a sense of comfort.”

To mark the 50-year anniversary of Aaron’s 715th homer, the Atlanta History Center will open a new exhibit to the public celebrating Aaron on Tuesday that will remain open through the 2025 All-Star Game in Atlanta. MLB Commissioner Rob Manfred is expected to attend a preview of the exhibit on Monday.

Aaron’s bat and the ball he hit for the record homer, normally housed at the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, New York, will be on display at Truist Park on Monday.

The Hank Aaron Invitational is designed to encourage high school players from diverse backgrounds to play at higher levels. Alumni of the Hank Aaron Invitational include Cincinnati pitcher Hunter Greene, who participated in 2015, and Braves outfielder Michael Harris II, who played in 2018.

Major League Baseball also supports other initiatives, including the Andre Dawson Classic, designed to promote diversity in the sport.

“For me, just having somebody that looked like me that could be that successful and do the things he’s done, the road he paved for players like me, that’s pretty huge,” Harris said Friday.

Despite those efforts, the number of Black players on major league rosters has declined. A study done by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport at Central Florida revealed African American players represented just 6.2% of players on MLB opening day rosters in 2023, down from 7.2% in 2022. Both figures from the institute’s latest reports were the lowest since the study began in 1991.

A recent spike in the number of African American first-round draft picks provides hope that MLB’s efforts, including the Hank Aaron Invitational, may make a difference.