Emmet Jopling Bondurant II knew about the civil rights movement when he was a student at the University of Georgia in the 1950s, but he didn’t join it.

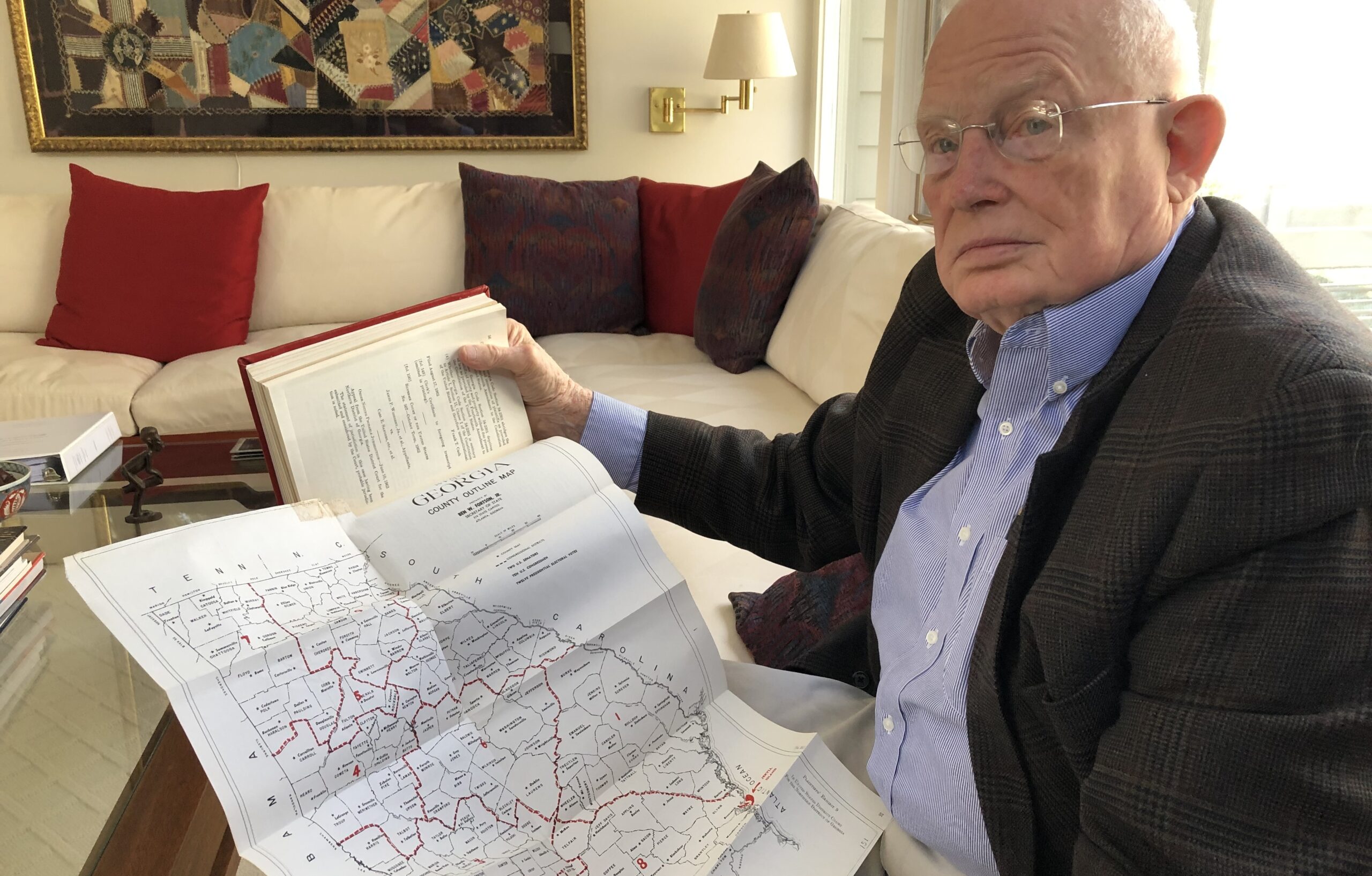

“I was trying to get through college,” the burly, white-haired 82-year-old said in an interview. “And I’m embarrassed to say I was not involved. I should have been involved much sooner.”

But, as a 26-year-old lawyer, he soon took part in one of the most important voting rights cases before the Supreme Court in the 1960s — one that ultimately required states to put equal numbers of people in congressional districts.

Fifty-five years later, in a case that bookends his legal career, Bondurant is returning to argue before the high court in a case that asks whether politicians can draw political boundaries to benefit their own political party at the expense of the other party.

“They did not want the districts changed”

As a young law student at the University of Georgia, Bondurant was frustrated by the segregationists dominating Georgia politics and started looking at how elections worked in the state and around the country.

Later, he delved into the state’s congressional districts.

Urban populations had grown a lot leading up to the 1960s, but politicians weren’t adjusting the districts, according to historian Doug Smith, author of On Democracy’s Doorstep: The Inside Story Of How The Supreme Court Brought “One Person, One Vote” To The United States.

“I can’t imagine any state legislature just forgetting — not getting around to redistricting — I think it was absolutely a political choice,” said Smith.

In Michigan, for example, about 800,000 people lived in the largest district, which included Detroit. Just over 117,000 people lived in the smallest district. Yet both districts each elected one member to the House of Representatives, giving the voters in the smaller district far more sway than in the larger one.

In states where people of color could vote, malapportioned districts tended to give them less political power, and it generally gave Congress and state legislatures a rural bias, said Smith.

“You had a rural minority that was able to pass labor laws that were not favorable to workers in the cities,” said Smith.

Bondurant compares the practice at that time to partisan redistricting, also called gerrymandering, today.

“They did not want the districts changed” said Bondurant, about how politicians approached congressional districts in the 1960s. “They did not want new competition. They didn’t want new voters. They wanted the old voters they already had. And that is one form of gerrymandering.”

In this week’s case before the Supreme Court, Bondurant is set to argue for the side asking the court to block the practice, and he brings some special experience to the topic.

Wesberry v. Sanders

After Bondurant joined a law firm in Atlanta, he was recruited by a group of older lawyers to work on a case, Wesberry v. Sanders, about the imbalance between congressional districts.

The goal was for the courts to force states to draw new political maps with equal populations in each district. It eventually went to the Supreme Court.

Bondurant spent his nights and weekends working on the case for free. The only break was for home football games at the University of Georgia.

“That was understood to be a religious holiday of sorts,” he said.

The work was especially time consuming because of the data involved. It was before even hand-held calculators.

“You were working with the 1960 Census, and a legal pad, and a pencil,” Bondurant said. “And if you made a mistake in one area it affected everything you’d done, like a series of dominos.”

On November 18, 1963, Bondurant argued before the Supreme Court for the first time. He was 26.

Chief Justice Earl Warren mispronounced Bondurant’s name at the beginning of the hearing, but the young lawyer seemed unphased, and delivered his arguments.

“A bulldog”

Bondurant has won plenty of big corporate cases. But he says even people with few resources should have someone to speak for their interests, whether in Congress or the courts.

In the 1990s, Bondurant helped secure the exoneration of Gary Nelson, who spent about a decade on death row.

In the 1980s, Bondurant risked his reputation arguing for an Atlanta woman in a gender bias case.

And Bondurant has backed small civil rights groups like the Asian American Legal Advocacy Center in Atlanta, founded by Helen Kim Ho.

“Ultimately the work and the fight was ours, but he stepped in at a critical time,” Kim Ho said, “and we’re grateful for it.”

Around the 2012 election, Kim Ho’s group was registering new citizens to vote. It got an intimidating letter from Georgia’s secretary of state.

She contacted Bondurant, and when he let the state know he was involved, it backed off.

Kim Ho sees it as a great example of how Bondurant is an ally to people of color.

“What you want is a lawyer who is angry, and willing to be a bulldog for you,” she said.

In 1964, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Bondurant’s side. In states with more than one House representative, districts must have the same population.

The ruling gave more power to urban and suburban areas, and it forced politicians to get more creative about how they draw districts, said Doug Smith, the historian.

“It’s at that point then when the drive toward gerrymandering really starts to kick up to another notch,” Smith said.

55 years later, Bondurant is set to argue before the Supreme Court again.

This time he’s asking the court to block partisan redistricting in North Carolina.

Although the state is closely politically divided, the legislature ensured that Republicans would dominate the congressional delegation.

Bondurant has no plans to retire, or quit trying to improve democracy in the country through the courts.

“I’d rather spend my time doing that than playing golf, in part because I play golf so badly that the opportunity not to play is itself a positive,” Bondurant said. “But, this is really important stuff, and it’s very fundamental.”

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))