The United States has become a less safe place for journalists, and the threats they face are becoming the standard, according to a new report by an international press freedom organization.

Reporters Sans Frontières, or Reporters Without Borders, dropped the U.S. to No. 48 out of 180 on its annual World Press Freedom Index, three notches lower than its place last year. The move downgrades the country from a “satisfactory” place to work freely to a “problematic” one for journalists.

“Never before have US journalists been subjected to so many death threats or turned so often to private security firms for protection,” the report stated.

Ten journalists have been physically attacked this year, and 46 since 2017. In January, one reporter was punched in the face and her phone stolen, while interviewing voters in California.

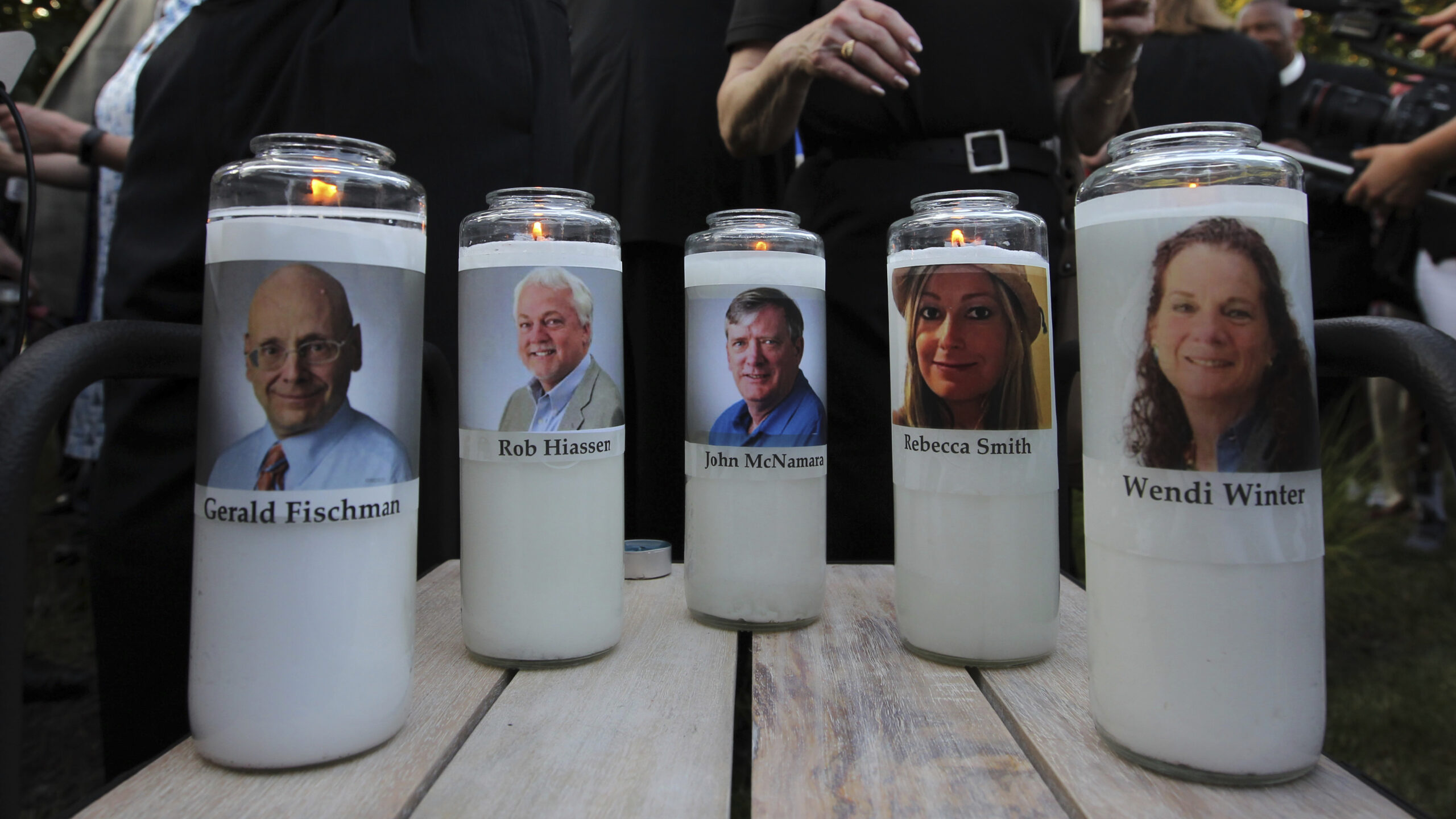

Last June, five people were killed while working at the Capital Gazette newsroom in Annapolis, Md. The man accused of shooting them had threatened the publication for years leading up to the attack.

The report also pointed a finger at President Trump who, it said, “exacerbates” press freedom problems with his repeated declarations that journalists are an “enemy of the American people,” his accusations of “fake news,” his calls to revoke broadcasting licenses and his efforts to block specific outlets from access to the White House.

“The president’s relentless attacks against the press has created an environment where verbal, physical and online threats and assault against journalists are becoming normalized,” RSF Interim Executive Director Sabine Dolan tells NPR.

She calls the situation in the United States “unprecedented” but says Trump enhanced an environment that had already declined under President Barack Obama.

“Even before President Trump, the Obama administration was aggressively using the 1917 Espionage Act to prosecute more whistleblowers than any previous administration combined,” she says.

Courtney Radsch, advocacy director at the Committee to Protect Journalists, tells NPR that RSF’s findings are not surprising. Reporters in the United States have been attacked by both police and protesters while covering demonstrations, and others have been targeted at the border by authorities, she says. “The anti-press rhetoric, coming from the highest office, can kind of set this tinder on fire,” says Radsch.

Accusations of fake news have led to exponential increases in imprisoned journalists. In 2016, nine journalists were imprisoned on false news charges worldwide, according to the CPJ. That number rose to 28 in 2018, with an increasing number of authoritarian leaders relying on the term to repress journalists.

The Americas experienced the greatest press freedom corrosion in the world, according to the index, from attacks at protests in Brazil to coordinated killings in Mexico.

Researchers identified the most oppressive countries as North Korea and Turkmenistan, where the governments maintain a strong grip on their countries’ flow of information and silence journalists who defy them through harassment, arrest, torture or killing.

Norway ranked as the safest country for the third year in a row, followed by Finland.

And Ethiopia offered a glimmer of hope under the new leadership of Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, who released detained journalists. The country rose 40 spots in the index ranking.

Yet only 24% of the 180 countries and territories in the assessment were classified as having a safe or satisfactory environment for the press.

Dolan says that globally, minorities and female journalists under the age of 35 have experienced a growing number of threats and online harassment.

People are consuming information that “already confirms their opinions and views” regardless of veracity, says Dolan. “And so it’s reinforcing these antagonistic feelings that people cultivate against the media, amplifying this discourse for certain segments of the population.”

The report also stated that disinformation, spread on social media, has become a grave problem for journalists and minorities. In Myanmar, hate speech online targeted the Rohingya, a Muslim minority, setting the backdrop for a brutal crackdown and the imprisonment two Reuters journalists who were investigating Rohingya killings.

RSF’s rankings were determined by a multi-language, 87-question survey for media professionals and experts. The responses were then combined with data on abuses against journalists.

“There is this growing trend of this climate of fear for journalists as hate against them from heads of states percolates into large segments of the population and this degenerates into violence,” says Dolan.

Copyright 2019 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))