The coronavirus has dealt a body blow to U.S. workers. So far, it’s women who are paying much of the price.

The Labor Department says more than 700,000 jobs were eliminated in the first wave of pandemic layoffs last month. Nearly 60% of those jobs were held by women.

Perla Pimentel was one of the first economic casualties. She worked as an event coordinator in Orlando, helping to arrange group meetings in the tourist mecca.

Six weeks ago, groups that were planning meetings in Florida began to cancel, as concerns about the coronavirus mounted. By the middle of March, Pimentel was out of a job.

Since then, millions of people across the country have been laid off, as Americans were ordered to hunker down and wait out the pandemic. Central Florida, with its heavy reliance on tourism, has been especially hard hit.

“It feels like everybody you know is either out of a job or is one degree of separation,” Pimentel said.

Two weeks after she was laid off, Pimentel’s father lost his job as a transportation contractor for Disney World. The warehouse where her mom works has also begun to furlough employees. For now, only her brother has a dependable paycheck.

“My brother actually works as a pizza delivery person,” Pimentel said. “He’s doing pretty well, as you can imagine. A lot of people are ordering out.”

When Americans started staying home in droves last month, restaurants, bars, and hotels were among the first to feel the squeeze. Because women make up the bulk of the workforce in those industries, the pink slips so far have been especially pink.

Just three months ago, women had overtaken men to capture a majority of the jobs on U.S. company payrolls. With job losses in March falling disproportionately on women, they’re now back in the minority, albeit just barely.

Ericka Dobrowski lost her job as a front-desk clerk in a big Chicago hotel when reservations suddenly dried up.

The hotel where she worked has 1,200 rooms. “Last I checked, we had three rooms occupied. So, it’s insanity,” Dobrowski said.

Her sister, who worked for a different hotel, is also out of work now. Dobrowski was able to file for unemployment early, before the much larger wave of layoffs that followed.

“I’ve been relying on that the last couple of weeks now,” she said. “It’s been enough to get by for me but it’s not been great, obviously. And especially, the Illinois unemployment benefit office is absolutely overwhelmed right now.”

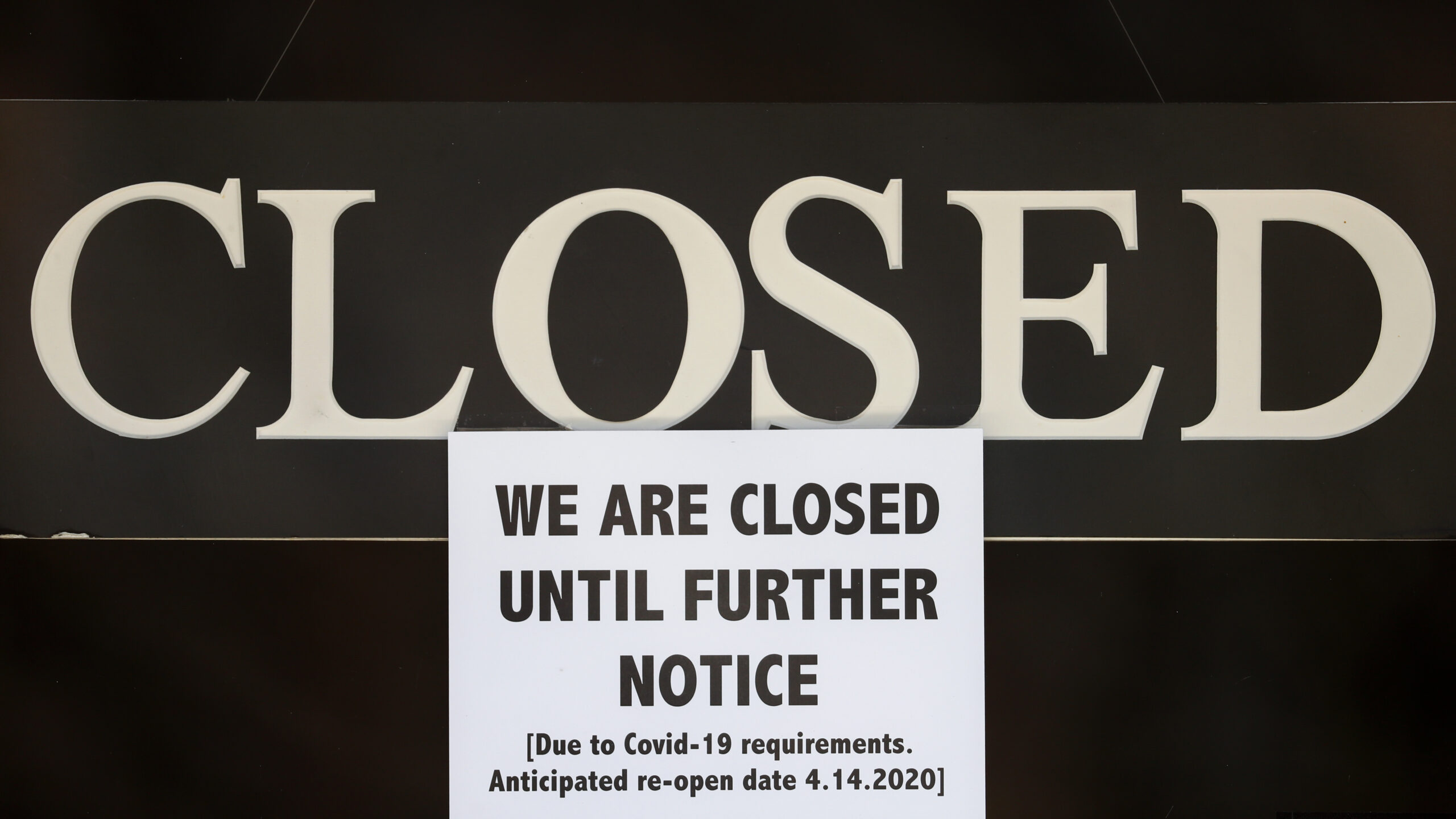

The fact that so many women are at the front of the unemployment line is a contrast to the last recession. It 2008 and 2009, male-dominated industries like construction and finance were the first to feel the slowdown. This time, a lot of high-contact workplaces like beauty parlors, shoe stores and dentist offices — where women outnumber men — were quick to close their doors.

Men may catch up, though, as layoffs continue to spread.

Robby Bissell lost jobs at two different restaurants where he worked in Lexington, Ky.

“I was working two jobs because I was saving up to actually move out to Los Angeles,” the aspiring actor said. “That’s kind of all been put on hold as of right now. Which really stinks.”

University of Michigan economist Betsey Stevenson estimates some 15 million Americans are now in similar straits, having lost their jobs because of the virus, with no clear indication of how long stay-at-home orders will remain in effect.

“This is not like normal times when people are unemployed and that means that they’re pounding the pavement trying to find work,” Stevenson said. “People aren’t able to go to work and we’re trying to figure out who’s going to be easily recalled and who’s going to be able to financially make it until they’re recalled.”

For both women and men, Stevenson said, what the future looks like after the pandemic will depend a lot on whether they have a job to go back to.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))