One hundred years ago on Aug. 18, three-quarters of the states voted in favor of giving women — selectively white women — the right to vote, and the 19th Amendment was formally added to the Constitution.

But that was no thanks to Georgia, which was the first state to reject it.

In the years after the Civil War and Reconstruction, Georgia’s white political elite used all means to keep a movement tied to the North, and abolitionism, from taking shape. The women’s suffrage movement that took off more than 70 years earlier in Seneca Falls, New York, historically excluded the efforts of Black women.

Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporter Tamar Hallerman took a deep dive into the intersection of race and the suffrage movement in the Jim Crow South.

“Many leaders in the movement were based in the Northeast,” Hallerman said.

“Political leaders in Georgia saw the women’s suffrage movement as a threat from the beginning. They saw the ties of suffragist leaders to abolitionists of the day, including Frederick Douglass, and they were immediately suspicious.”

The Southern white, male establishment also saw the suffrage movement as a threat to their way of life. When small suffrage groups eventually did pop up around Georgia early on, events mostly barred Black women, and men, from participating.

“Many of them were well-educated, relatively well-off white women,” Hallerman said.

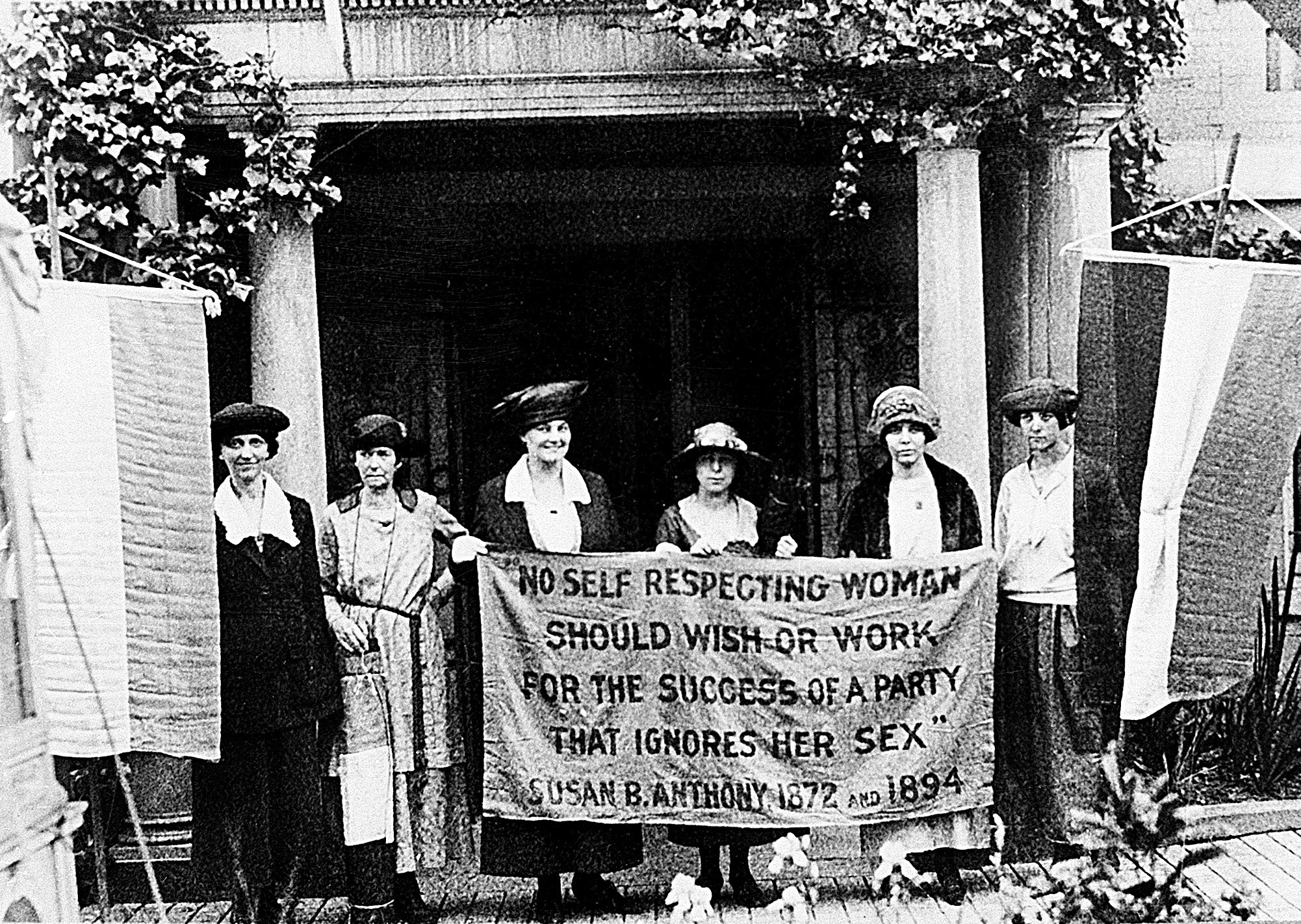

Susan B. Anthony, revered as a hero in the women’s suffrage movement, even told her longtime ally Douglass not to attend an 1895 Atlanta convention for the National American Women Suffrage Association. Anthony was afraid it would dissuade white Georgians from the movement.

Getting a new amendment added to the Constitution required three-quarters of the 48 states in the union. Mathematically, leading suffragists realized they needed to sway many white, conservative male leaders in the South. By the 1890s, Hallerman said leaders like Anthony were developing a so-called Southern strategy.

“The argument they came up with to sell women’s suffrage in the South was, ‘Hey Conservative leaders, we know that you don’t like that Black men can vote. Why not enfranchise, especially white women, so they can offset the votes of Black men,’” Hallerman said.

The 15th Amendment ratified in 1870 had already granted Black men the right to vote, by declaring that the “right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

But Black citizens were still disenfranchised through the use of Jim Crow tactics, including literacy tests, poll taxes and intimidation and violence.

Hallerman noted that 100 years later, Southern voters, especially in communities of color, still deal with modern-day voter suppression.

“It just goes to show how slow Georgia was to adapt to a lot of the changes that were coming from the rest of the country,” Hallerman said.

“You’re seeing those ripple effects now. It still is an ongoing story here in Georgia.”