For weeks, the world wondered whether President Trump would win a second term. Now that election officials and observers have declared his opponent “President-elect Joe Biden,” the world wonders whether Trump will concede.

So far, the president has not. Instead, he has said that he won the election “when you count legal ballots” and that he will pursue numerous challenges to the vote-counting process in court. Earlier in the fall, he had said he would agree to a peaceful transfer of power unless the election was “rigged.”

It seems increasingly inevitable that Trump will need to either give a concession speech or explain why he is refusing to do so. There is no legal requirement for it, and a refusal would not lengthen his lease on 1600 Pennsylvania Ave. or extend his powers beyond noon on Jan. 20.

But concessions have become all-but-official touch points in the process of American elections. And they have been of special value as part of the process when one party cedes the presidency to the other, because that is the clearest signal of commitment to the peaceful transfer of power.

Such a situation arose in 2000, when the Democratic nominee was the sitting vice president, Al Gore. He wound up conceding twice, first on election night and then again five weeks later. His first concession, in a phone call to Republican George W. Bush, was retracted a few hours later as more results came in and pivotal Florida, called once for each candidate that night, seemed to still be in play.

After five weeks of messy vote counting and recounting and countless legal maneuvers, the federal case of Bush v. Gore reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled 5-4 that the Florida fracas should stop. Gore could have carried his case further, to the House and Senate and the public at large. But he decided that while his prospects of success were uncertain, the costs and dangers were too high.

“Just moments ago, I spoke with George W. Bush and congratulated him on becoming the 43rd president of the United States, and I promised him that I wouldn’t call him back this time,” Gore said.

Gore also quoted Stephen Douglas, who lost to Abraham Lincoln in the fateful election of 1860: “Partisan feeling must yield to patriotism,” Douglas wrote then. “I’m with you Mr. President, and God bless you.”

Douglas was as good as his word. He not only conceded but embarked on a speaking tour of the South to urge his fellow Democrats to accept the election outcome and “preserve the Union.”

Douglas was not successful. Eleven states seceded, and the Civil War ensued. But his effort was more than a beau geste — it was a statement of the importance of abiding by the popular will in a democracy.

This has been at the essence of the concession all along. It is not just one 18th-century gentleman bowing to another; it is the affirmation of what the Founders had in mind when they rebelled against the crown of England in the name of “the people.”

Gore’s decision and concession ended the standoff and allowed a measure of healing to begin. It illustrated and amplified the value of the concession tradition, which has deep roots in U.S. history and has provided ineffable benefits at fraught moments in the past.

“When it comes down to it, it’s not the Army or the Navy that keeps the United States together,” John R. Vile, a professor of history at Middle Tennessee State University who is a student of the concession, told National Geographic magazine. “It’s the notion that we are bound together by certain great principles and that our similarities are more binding than our differences are.”

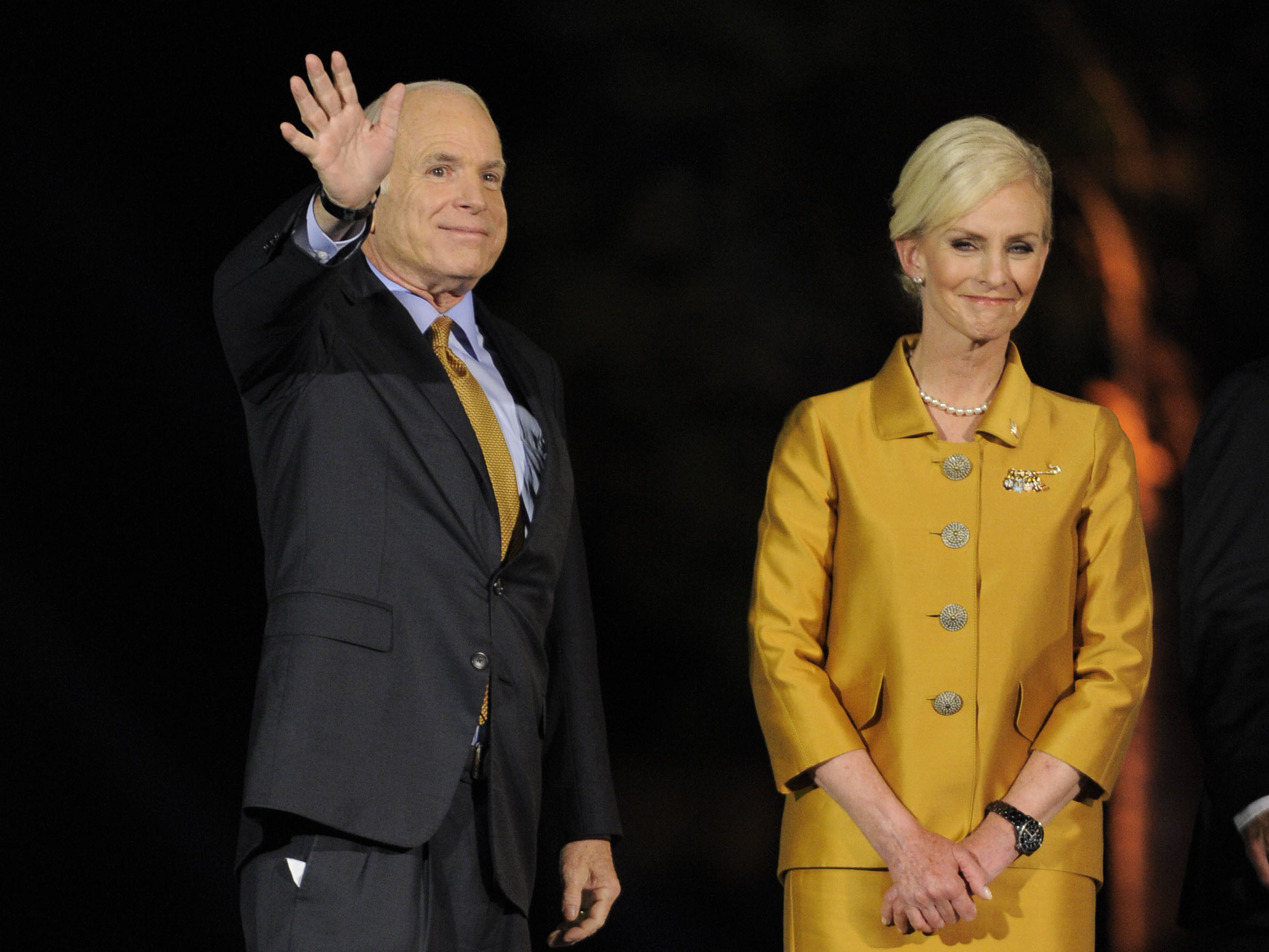

McCain 2008 as a model

Another recent example frequently saluted for its class and eloquence was Republican Sen. John McCain’s in 2008. McCain, too, was handing off the White House to the opposing party. Moreover, his own long and frustrating pursuit of the presidency had been ended that night by a junior fellow senator, Barack Obama.

The 2008 election was often bitter and ended in the midst of an economic crisis, but McCain chose to be gracious and patriotic in his remarks.

“The American people have spoken, and they have spoken clearly,” said McCain. “A little while ago, I had the honor of calling Sen. Barack Obama to congratulate him on being elected the next president of the country that we both love.”

McCain also took note of a salient fact of the moment — Obama’s achievement as the first African American to reach the Oval Office.

“This is a historic election, and I recognize the special significance it has for African Americans and for the special pride that must be theirs tonight,” he said. “Senator Obama has achieved a great thing for himself and for this country. I applaud him for it.”

Some believe that speech was the finest achievement in conceding ever witnessed. But that is not a distinction likely to be much prized by candidates going forward. In 2012, Mitt Romney gave a concession speech that sounded a lot like a victory speech. That may have been because his campaign by some reports had been so sure of winning that no concession speech had been contemplated.

All the way back

John Adams, the first president to be relieved by the voters after one term, is said to have congratulated Thomas Jefferson, the new president, in private. Thereafter the tradition was satisfied in like manner for generations.

With the coming of faster and more public means of communication, the more modern notion of a concession statement took form.

Historians often cite a telegram sent by Democratic nominee William Jennings Bryan to his Republican rival, William McKinley, as soon as the voters’ verdict was clear. He offered his congratulations and added: “We have submitted the issue to the American people and their will is law.”

Conceding has a special sting, of course, when it is incumbent upon an incumbent. Some have found it best to get it over quickly. President George H.W. Bush was in touch with Bill Clinton soon after the polls closed on election night in 1992, and President Jimmy Carter went further than that. When he conceded to Ronald Reagan in 1980, his public concession went out before the polls had closed on the West Coast.

A quick surrender may not be any less painful, but at least it does not prolong the agonizing wait. Perhaps the first of these quick surrenders was that of Republican President William Howard Taft, whose one term in office ended when he finished third in his reelection bid of 1912. Second place went to Theodore Roosevelt, who had been president between McKinley and Taft and was attempting a comeback as the nominee of the Progressive Party (sometimes called the “Bull Moosers”). But the congratulatory message Taft sent right away on election night went to Woodrow Wilson, the Democrat, who came out on top.

Conversely, one of the slowest concessions came four years later when Wilson was winning his second term. It was 1916, and the three most populous states at the time (New York, Pennsylvania and Illinois) all voted for the Republican challenger, Charles Evans Hughes. Some news reports initially declared Hughes the winner, and it took days for all the tallies to arrive.

Some Republicans cried foul, but Hughes did not, declaring “in the absence of absolute proof of fraud, no such cry should be raised to becloud the title of the next president of the United States.” When after two weeks Wilson’s narrow win was assured, Hughes sent a gracious telegram.

Tech changes tradition

The telegram was a favored method in the first half of the 20th century. Herbert Hoover sent one to Franklin D. Roosevelt the day after FDR’s 1932 landslide, promising to “make every possible helpful effort” to aid his rival’s transition and success in office. Hoover would subsequently try to involve FDR in his efforts to deal with the banking crisis of that winter, but FDR held out for a chance to begin with a clean slate after Inauguration Day — a sore point for Hoover and his defenders for many years thereafter.

Meanwhile, however, technology was moving ahead. Democratic nominee Al Smith had already made the first broadcast concession speech on radio in 1928 (ceding to Hoover), and Adlai Stevenson introduced television to the tradition in 1952. Since then, we have come to expect to see even incumbent presidents do the deed on the tube.

Which brings us to the present moment. Will Trump do it on Twitter? Will he make a speech and stick to the teleprompter version?

Or will he just say no?

The concession is not, after all, for the sake of its maker. It does nothing for the losing candidate but get it over with. The concession is, rather, for the sake of everyone who needs closure. That includes the losing candidate’s family, staff, campaign workers and party rank and file.

In other words, concession speeches are for everyone else but the candidate. But it is the candidate who must finally decide who and what he cares most about.

Stay tuned.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))