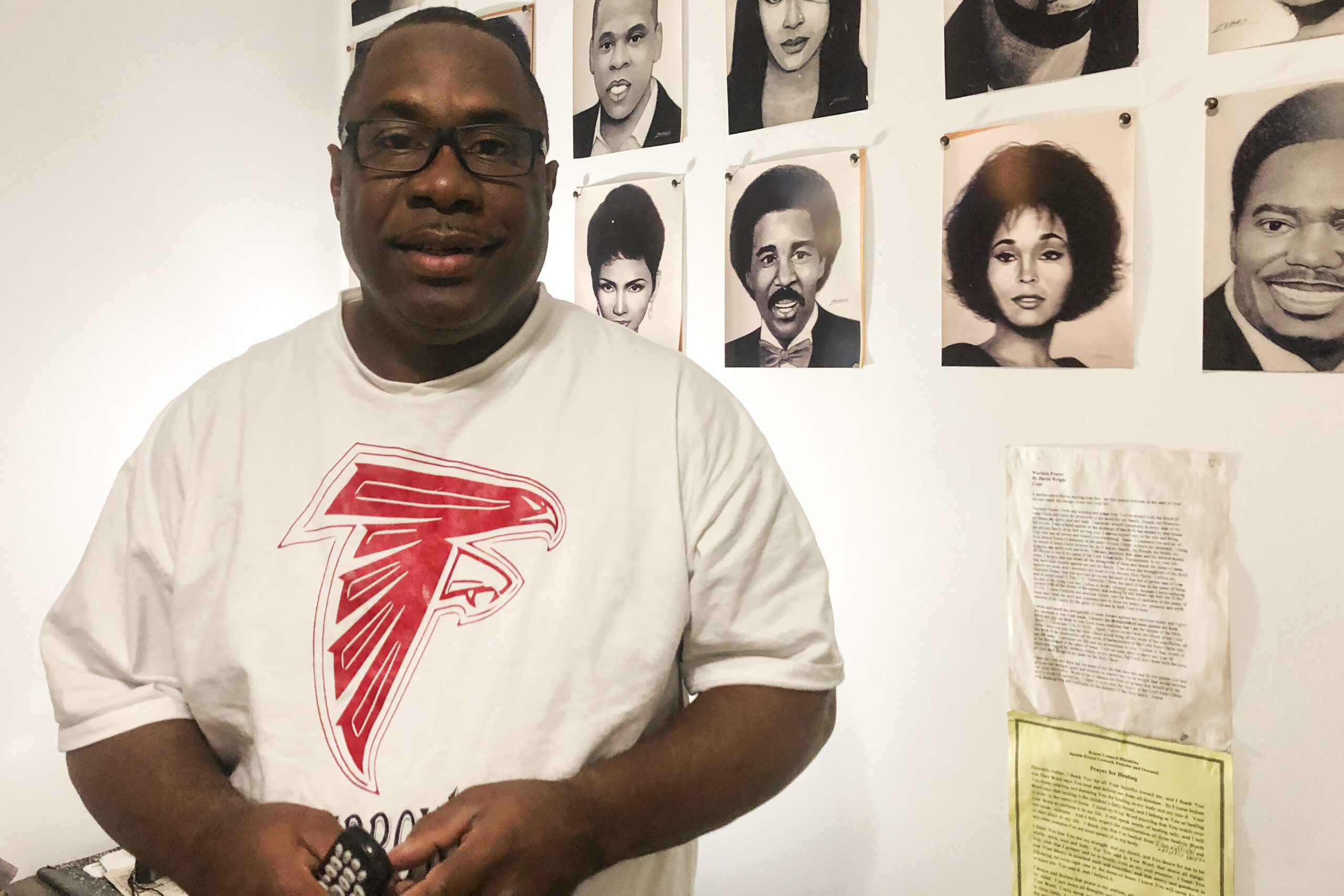

For more than five years, home for Armetrius Neason has been a hotel outside Atlanta. He’s adorned the walls with dozens of pictures of Black celebrities and icons. It’s the address on his driver’s license and where he receives mail.

But last year as the COVID-19 pandemic raged, the hotel accused him of owing $1,800 in back rent and threatened to lock him out, the 58-year-old said.

“I was packing my clothes. I really had nowhere to go,” he recalled during a phone interview.

Efficiency Lodge said Neason — despite his lengthy stay — was a guest it could kick off the property without filing an eviction case in court.

“If you go to a Holiday Inn and you don’t pay your room rate, the next day your key won’t work,” said Roy Barnes, a former Georgia governor and attorney for the lodge, which is co-owned by his brother, Ray Barnes. “It’s the same law.”

Neason’s struggles reflect the heightened risk of homelessness faced by motel and hotel dwellers during the pandemic, housing attorneys say. Many states do not clearly define when hotel and motel guests become tenants — a designation held by traditional leaseholders that gives them the right to contest an eviction attempt before a judge. Hotel guests, in contrast, can be removed summarily.

The legal gap made motel living riskier than typical home renting even before the pandemic. Now it’s even less stable, the attorneys say. Job losses during the pandemic have made it harder for millions of Americans to make rent. But hotel guests are excluded from a federal moratorium on evictions for people facing financial hardship during the coronavirus outbreak.

Hotel and motel residents in California, Colorado, Florida, Louisiana, New Jersey and Virginia have reported being expelled or threatened with immediate eviction over the past year.

“It’s people that are even more economically vulnerable than most low-income tenants,” said Alexis Erkert, an attorney at Southeast Louisiana Legal Services in New Orleans who has fought evictions at motels during the pandemic.

Hotel owners say they have also taken a hit during the COVID-19 outbreak and need paying customers to cover expenses.

“They just want their asset and their livelihood protected just like anybody else,” said Marilou Halvorsen, president of the New Jersey Restaurant and Hospitality Association.

In another recent hotel dispute in Georgia, Demetress Malone accused staff at Lodge Atlanta of removing his door, cutting his power, taking his air conditioning unit and changing his lock after he had trouble paying rent for the room he had occupied for roughly a year, according to a lawsuit he filed against the property. A call and email to an attorney for Lodge Atlanta, Frank C. Bedinger, was not returned. A judge sided with Malone in November, saying the hotel had to file an eviction case against him in court.

At Efficiency Lodge, a private security guard carried an assault rifle and pointed it at residents as he went door-to-door forcing them to leave in September, according to Neason’s attorney, Lindsey Siegel, and a lawsuit he and another current resident filed against the property. Siegel is with the Atlanta Legal Aid Society.

“I never seen nothing like that in my life, just to put a person out on the street,” Neason said. “You had to go then.”

Roy Barnes disputed that residents were forced out at gunpoint, saying security was searching for two people wanted for murder.

Neason, who works as a carpenter, came to the hotel in 2016 and was paying his weekly rent of $200, but said a hotel employee told him he didn’t have to pay the full amount during the pandemic. He was later presented with a bill for back rent, he said.

The room he lives in has a small kitchen with two electric burners. He’s hung colorful sports caps off hooks in one corner and keeps free weights near the television stand.

Advocates say lawsuits by hotel residents are rare, and many other removals go unreported.

“These are people who have already been stretched to their limits, are broken,” said Eric Tars, legal director of the National Homelessness Law Center. “Many of them assume, ‘I am just staying as a guest at this motel.’”

Federal data suggests increasing numbers of people are relying on motels and hotels for long-term housing. The number of students in the U.S. who identified a hotel or motel as their primary nighttime residence jumped by nearly a quarter between the 2015-2016 and 2017-2018 school years to more than 105,000, according to numbers submitted by states to the U.S. Department of Education.

But the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention excludes hotels or motels rented to a “temporary guest or seasonal tenant” — terms it leaves local laws to define — from its eviction moratorium in place through March. Some states have stepped up to try to protect motel dwellers.

New Jersey has its own moratorium that explicitly protects people who live continuously at motels and hotels and have no permanent housing to which they can safely or legally return. Halvorsen said dozens of hotels have reported guests who have taken advantage of the stricter rule by checking in and then refusing to pay or leave.

The attorney general’s office in North Carolina warned nearly a 100 hotels and motels in the state early in the pandemic that their residents could qualify as tenants. Georgia’s Department of Law offered similar guidance.

But housing experts say with no clearly defined rule about when a hotel stay is no longer temporary or seasonal, residents of such properties remain vulnerable to quick expulsion when they can’t pay.

In January, a DeKalb County judge ruled that Neason was a tenant and blocked the lodge from evicting him without going to court. The lodge has appealed.

“Who do you layoff and who gets foreclosed on if nobody pays?” Roy Barnes asked. ”This is not an issue that’s all good on one side and all bad on the other.”