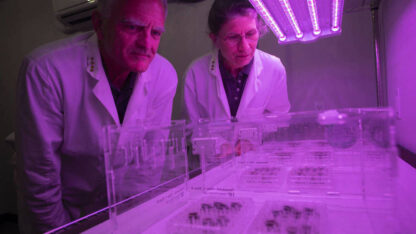

Emory University professor Cassandra Quave travels around the world to search for new medicines from plants. She learns from traditional healers, and then she takes plants back to the lab to study their potential to fight deadly infections.

“Everyone right now is, of course, focused on COVID. And for good reason,” she says. “But at the same time, lurking in the background, antibiotic resistance continues to be a major, major problem.”

Quave has overcome obstacles in her scientific journey, including being born with congenital birth defects, leading doctors to amputate one of her legs when she was a child.

“It definitely instilled a lot of resilience in me. And in the pursuit of science, there’s no tool as important as resilience because scientists face a lot of failure,” she says.

Quave has a new memoir, called The Plant Hunter. Upcoming events for her book include in-person talks at Emory and at the Chattahoochee Nature Center.

Excerpts from the interview

How her experiences as a child going through multiple surgeries shaped her interests

“Undergoing so many surgeries and just kind of being immersed in medicine from a young age, I had a deep appreciation for the value of both surgery and pharmacology. But I also had a curiosity for other ways that different cultures look at medicine and where that put me as a young disabled girl.”

Why she focuses on antibiotic-resistant infections in her drug discovery work

“In 2016, it was estimated that there were around 700,000 people that died each year due to untreatable antimicrobial resistant infections. And that number is projected to reach 10 million per year by 2050. We have a real drought when it comes to the discovery of new classes of antibiotics. And that’s where I’m really trying to help fill in that gap with our study of plants.”

Why she’d like to see more people studying plants for their medicinal properties

“We’re in the midst of a biodiversity crisis, and a crisis in the loss of languages. And with language loss, we also see loss of traditional knowledge concerning the uses of these plants. So there are many different areas where scientists can make a really big contribution to helping us understand how these work.”

On the difference between indigenous knowledge of plants and untested claims about natural remedies, including for COVID-19

“There’s a vast, vast chasm between the worlds of true indigenous traditional medicine and knowledge that has been passed down for millennia versus marketing hype that you see, basically, with these efforts to make money off of plants and in some cases to the detriment of human health.”

On ongoing challenges for women in science

“The truth is, science is really competitive. Part of the reason it’s so competitive is the resources are very limited … And I think women across the board tend to carry the brunt of caregiving much more so than their male colleagues. And we need to do more to kind of help even out the playing field, starting with better support, maternity leave and childcare support where possible.”