Polycrisis

The simplest description of polycrisis might be that all of our old problems are occurring in a new way.

“All the crises we are seeing have always occurred,” says Professor Danny Ralph of Cambridge’s Centre for Risk Studies, “they are kind of Biblical (famines, wars, pestilence). What has changed is the rate at which these chaotic events are hitting us. If you don’t have this word in your vocabulary you might think ‘Don’t worry, we’ll fix this problem and get back to normal.’ “

Or, as a report published January 11, 2023 by the World Economic Forum put it: “A cluster of related global risks with compounding effects, such as the overall impact exceeds the sum of each part.”

Ralph says that increased connectedness is what marks the polycrisis of 2023, pointing to the rise of social media or China’s role in the global economy in the last two decades as gamechangers.

“The shocks in one part of the world now move very rapidly, globally. The connectivity that gives us fantastic economic efficiency in quiet times also transmits damage and fear.”

Out of the maelstrom of crises, Ralph identifies climate change as “the one that won’t go away.”

But on the positive side, “it allows us to face many concerns that go far beyond climate by emphasizing that we live on a connected planet.”

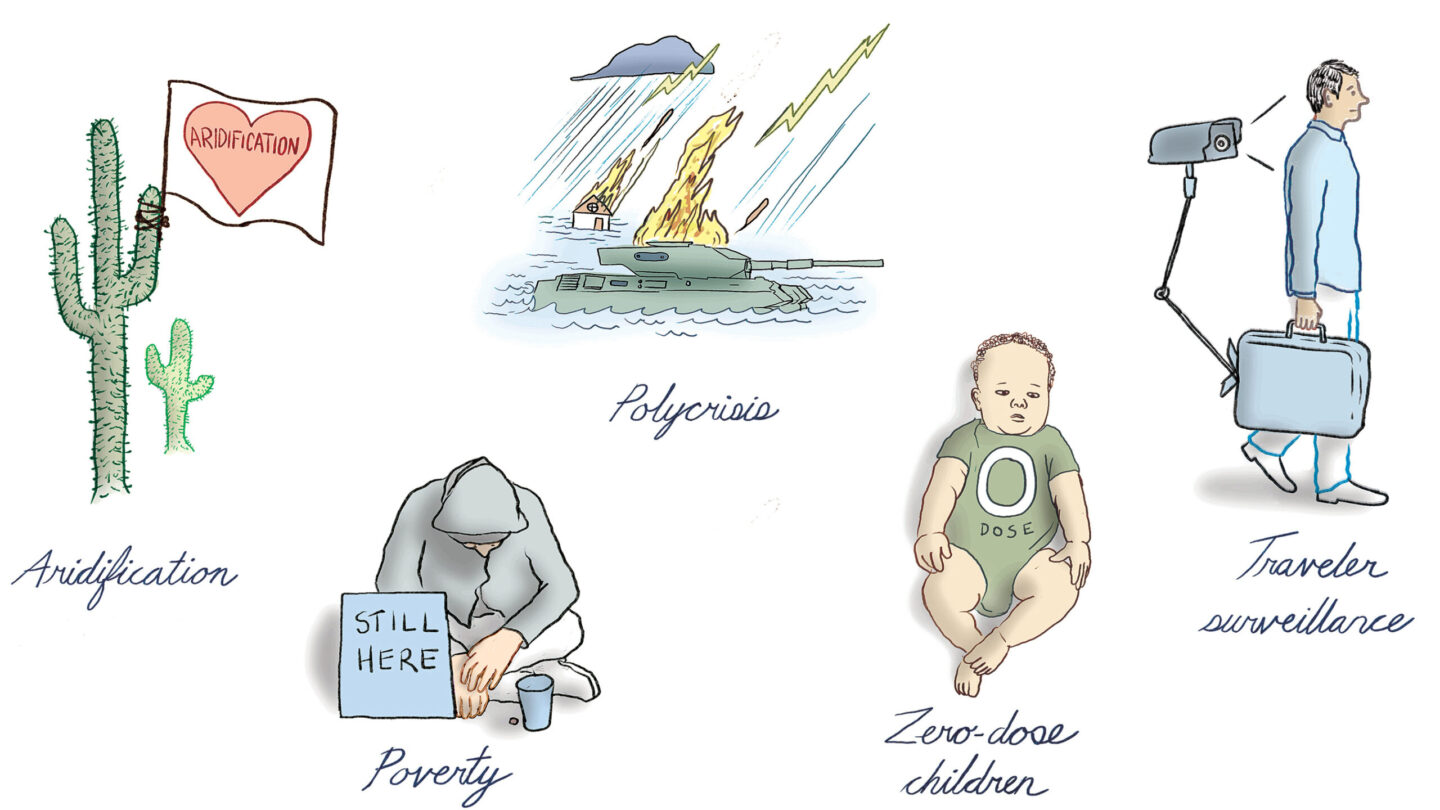

Poverty

Poverty is certainly not a new word, its usage stretching back to Biblical days, Latin and beyond, and neither is the concept. The U.N. has vowed to eliminate extreme poverty by the year 2030 in its Sustainable Development Goals. But the consensus is that poverty is reaching worrying new levels, and this target is now unlikely to be met. That’s why you’ll be hearing a lot about poverty in 2023.

Professor Sabina Alkire, director of the Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative, says that the current food and fuel crises will impact poverty in a major way in 2023, this on top of the impact from the COVID-19 disruption.

“The trends of poverty reduction before the pandemic — that has gone back 10 years.”

Last year, the World Bank announced that during the pandemic about 70 million more people were pushed into extreme poverty (subsisting on $2.15 a day or less) due to the COVID-19 pandemic’s effect on jobs and education. That’s the largest increase since records began in 1990.

The educational losses may keep people in poverty for longer, says Alkire, who warns that the hidden crisis is in the classroom. “After the pandemic many children have not gone back to school, and there is a lack of teachers. There will be an unprecedented setback in educational achievements.” which means more poverty.

Despite the gloom, Alkire says that we can take inspiration from how some countries have overcome intense hardships in recent years:

“Between 2005-2021, 415 million people left poverty in India. That’s a change at an historic level. Sierra Leone had the fastest poverty reduction of any country in the world between 2013-2017 and that was during the years of the Ebola crisis.” In both cases, boosting access to sanitation, cooking fuel and electricity along with supporting health, education, and social protection systems were key.

Traveler surveillance

Three years on from the pandemic, as the world tries to live with the virus, airports are getting busy again. As a result, some experts are advocating traveler surveillance — testing and gathering data rather than preventing people from entering a country as a way to keep an eye on any potential harmful COVID-19 developments.

In late 2022, China abandoned its zero-COVID policy, which saw city-wide lockdowns and quarantine camps. It was one of the last countries to retain onerous restrictions. Lawrence Huang from the Migration Policy Institute says that pre-departure and on-arrival testing will continue to be valuable as it helps track possible variants. And it’s not just travelers who are being surveilled in the effort to keep ahead of COVID. The United States, Australia and countries across Europe have started to recommend analyzing wastewater samples from inbound flights to identify caseload and variants.

“This will help us understand the risks and to mitigate them rather than try to eradicate them,” Huang says. Though, he notes, things could change quickly.

“If a new variant was bad enough some countries would go back to hard border arrangements. But the evidence is that these measures do not stop the virus from coming; at best they can delay it.”

Wasting

In 2022, the World Food Programme (WFP) reported the number of hungry people worldwide had increased from 282 million to around 345 million since the beginning of the year. With continuing damage wrought by conflict, climate change and high fuel and food costs, that grim number looks set to rise. Hence why last year over half a billion dollars was raised to combat child wasting — the most life-threatening form of malnutrition in which a child has very low weight for their height.

Jeanette Bailey is the Nutrition Research and Innovation Lead at the NGO the International Crisis Group and says that the world needs to seize on this momentum. “Famine is a man-made condition. Ultimately, it’s a collapse of economic, political and financial will,” Bailey says. The WFP reports Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen are among the countries facing food emergencies.

“On any given day we see 50 million children under the age of 5 suffering from wasting. Malnourished children are more likely to become sick and die of other illnesses and sick children are more likely to become malnourished. It’s a vicious cycle.”

Despite progress for decades, it’s getting worse, driven by COVID, conflict and supply chain disruptions. But, Bailey says, it is a “highly solvable problem” because there is fast-acting therapeutic food available around the world, like peanut butter paste supplements. She says donors need to make sure local governments and organizations are equipped to access hard-to-reach locations as well as making sure community health workers are trained in how to recognize and treat malnutrition.

Zero-dose children

Despite the progress of immunization in the last two decades — 78% of children received routine vaccines in 2020 compared to 59% in 2000 — a growing number of children are missing out completely. “Zero-dose” children are those who had never received any of even the most essential vaccinations –diphtheria, whooping cough and tetanus. Before the pandemic, they numbered an estimated 13 million. It’s now believed there could be as many as 18 million.

“We lost 30 years of progress in 3 years,” says Lily Caprani, Head of Global Advocacy for Health and Vaccines at UNICEF. The decline has been blamed on an uptick in conflict, a spread of misinformation and pandemic-related supply chain disruptions.

Caprani notes that the term captures something beyond vaccination rates.

“It’s a proxy indicator for a child living in a community deprived of clean water, healthcare and nutrition and it matters because those communities tend to be the epicenter of outbreaks of highly contagious diseases.”

These communities may be left out access to better living conditions due to their physical location or because of their religion, ethnicity or gender.

Tarmac to arm

Aid agencies are fond of publishing eye-catching photos of urgent supplies being flown into crisis-hit areas and offloaded onto runways.

Emily Janoch, Senior Director for Thought Leadership, Knowledge Management and Learning from CARE USA says that this was notable during the rollout of the COVID-19 vaccine.

“A lot of success was measured in terms of, ‘did we get the thing to the tarmac at the airport?’ “

But Janoch says this doesn’t really tell the full story.

“It’s only meaningful if humans got the service. Dropping it on the tarmac doesn’t accomplish the goal.”

Janoch contends that when a government or NGO or donor wants to help with any needed service — be it vaccines, other medical treatments, personal protective equipment, food — they must take into account the delivery costs in countries with struggling health systems. Hence, “tarmac to arm.”

Janoch says that donors should be thinking about the people at the end of the chain.

“Are you investing not just in the materials but in the distribution systems that allow humans to get served, including paying for someone to walk up a mountain with a cooler on their back?”

Gender food gap

Another measurement causing alarm is how many women around the world struggle to feed themselves. This is known as the gender food gap.

Numerous studies have shown that women are underpaid, sidelined in the labor market and required to undertake unpaid care and housework. This means they are more likely than men to live in poverty.

“One hundred and fifty million more women and girls don’t know where their next meal is coming from, compared to men and boys” Janoch says, and notes that in many countries women also lose access to safety nets “as they are not identified as heads of households or considered to be formal workers.” One estimate shows that there are 126.3 million more women than men who are hungry.

Janoch says the gap itself is concerning as is its fast growth.

“In 2018 that number was around 18 million. That’s the equivalent of every woman in California being affected four years ago to every woman in the United States being affected now,” she says.

Aridification

California started 2023 with extreme flooding that caused at least 19 deaths and hundreds of thousands to be without power. It is a far cry from what California is increasingly getting used to — longer and more intense droughts. Some experts like Barron Joseph Orr, lead scientist for the U.N. Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), warn of aridification — the increasing mismatch between supply and demand of available water. “The drier conditions become, the more expensive it will be to plant staple crops in some regions. Will it be economically viable to grow corn or maize if conditions get drier?” Orr asks. “Consider how many people that will affect in the future if we don’t continue to adapt.”

He says research shows cities as well as farming areas are likely to be affected.

“In the most extreme example, 75% of the global population could be in drier conditions by 2050. There will be significant adaptation that needs to take place in urban environments too.”

Orr says that much of this could be avoided, “if we keep climate change to 1.5 degrees.”

Climate impact resilience

So far the key goals may not have been achieved–Orr says that the world has “utterly failed” to stop or slow greenhouse gas emissions, hence why 2023 is the year to encourage resilience –adopting strategies to prepare for and help blunt the impact of climate change.

For example, he says governments could encourage better land management.

“We have already converted 70 to 75% of terrestrial natural ecosystems for human use,” Orr says. “That means we only have about 30% to play with. We need every bit of that to remain as natural as possible.”

And, he says, farming practices need to change. Thirsty crops could be replaced with varieties that require less water, and farmers should be incentivized to reduce dependence on chemicals in favor of sustainable treatments to help the soil store carbon–which it can do if it is healthy.

“It would put carbon back where it belongs, in the ground. That helps draw it down from the atmosphere. Not only does this mean greater soil fertility, and therefore productivity for farmers,” Orr says “but it enables biodiversity to flourish underground which is essential for nature above ground.”

At the micro level, Orr says individuals can make a difference when they buy groceries.

“If you’re supporting agriculture locally, you are putting those farmers in a better position to be adaptive.”

Callout: Readers, if you have additional buzzwords you’d like to share, send the term and a brief explanation to goatsandsoda@npr.org with “buzzwords” in the subject line. We may include some of these submissions in a follow-up story.

Thanks to Tara Kirk Sell, Caitlin Rivers and Amesh Adalja of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health for their contributions.

Andrew Connelly is a British freelance journalist focusing on politics, migration and conflict. He tweets @connellyandrew.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))