Freaknik made springtime in Atlanta unforgettable during the mid-‘90s.

“I say it’s a cultural phenomenon where we had a group of 200,000 plus at one time, African-American youth in the city for a fun, leisure and entertainment weekend,” former Underground Atlanta General Manager George Hawthorne said. “I think the Freaknik name as you know is a brand that is recognizable across the country.”

The yearly festival in Atlanta began in 1982 as a picnic for local college students and evolved into a meeting ground for black spring breakers and people of all ages around the nation.

“Kids describing meeting each other falling in love [at Freaknik]… One guy brings all these puppies because he’s like, ‘Girls love puppies.’ One guy described having a python animal … that was a good way to get attention,” assistant history professor Ansley Quiros, who’s studied the event, said.

Freaknik’s lasting impact can be described as both reverential and notorious. In 2010, the festival was immortalized in Adult Swim’s “Freaknik: The Musical.” Rappers and singers still reference it in their lyrics. But Former Atlanta Mayor Kasim Reed, who is on the record as having attended in the ’80s, vowed to be tough on events trying to use that name during his tenure.

Now, more than 20 years after its heyday, Carlos Neal, an Atlanta-based party promoter with After 9 Partners, is trying to recapture and resurrect that legacy.

Aiming To ‘Reshape This Event’

This isn’t the first time an event by the name of Freaknik has been thrown in Atlanta — or in the country — since the official festival ended infamously by 1999, following crime and complaints around the event.

But Neal isn’t letting the more negative parts of the legacy stop him.

“We’re able to now reshape this event in a way that no one … either couldn’t from a promotional standpoint, probably from a cost standpoint or from a care standpoint designed to do,” Neal said.

Neal said he’s invested his life savings into the Freaknik Festival, which is slated to happen in the Lakewood Amphitheatre on Saturday, June 22. Rappers Luther “Uncle Luke” Campbell, Bun B, Foxy Brown and Da Brat are headlining.

“I’m only one person right now, and I’m funding this all myself,” he said.

Over the years that Freaknik was popular, self-funded events were normal but risky for organizers. In 1995, promoters lost $100,000 when students chose to go to Piedmont Park instead of Lakewood Fairgrounds where their events were taking place, according to The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution.

Quiros, author of “Partying ‘The Atlanta Way’? Freaknik and Black Governance in 1990s Atlanta,” said she’s unsure if the upcoming festival will live up to its original form.

“I’m skeptical that something that’s like hyper-organized and especially sponsored in some way or [with] corporate ties in some way will have the same feel as the original Freaknik,” Quiros, Atlanta-native, said. “It can still be great. But the beauty of the original was the spontaneity of the young people.”

Sharon Toomer, who describes 1982 to 1991 as the best years of Freaknik, agreed.

She was one of the founders of the event when it started in Piedmont Park. Six members of the Washington D.C. Metro Club planned it during a meeting at Spelman College.

The name of the event was suggested by her college colleague Rico Brown, who gained inspiration for it from a popular Rick James song and dance at the time.

“There were about 60 of us [in 1982],” she said. “We centered around camaraderie, party, music.”

The following years, Freaknik evolved and attracted students from around the U.S. and even Canada, according to Toomer.

She credited the Atlanta University Center, which is composed of four historically black colleges and universities, as having a “unique camaraderie” that attracted other students to the area for spring break.

On The National Stage

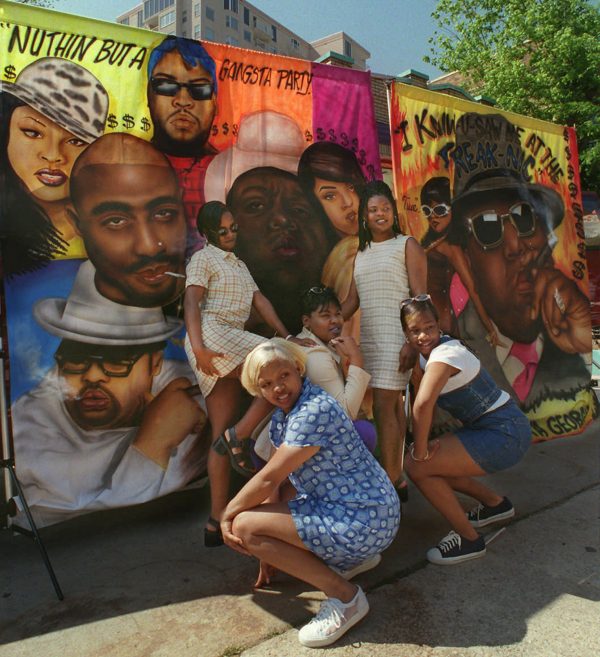

Freaknik gained national attention with mentions in Spike Lee’s 1988 film “School Daze” and in Luther Campbell’s “Work It Out” music video in 1993. With the event’s fame came thousands to the city ready to party.

By 1994, around 200,000 people were coming to Atlanta to partake in festivities around Freaknik, causing major gridlock on Atlanta’s streets, according to The Atlanta Journal and The Atlanta Constitution.

“It kind of evolved into the different components and different events that were scattered out all over the city,” Hawthorne said. “Parties at different clubs and restaurants around town and then just a free-for-all sometimes just ‘a rolling roadshow,’ as I called it.”

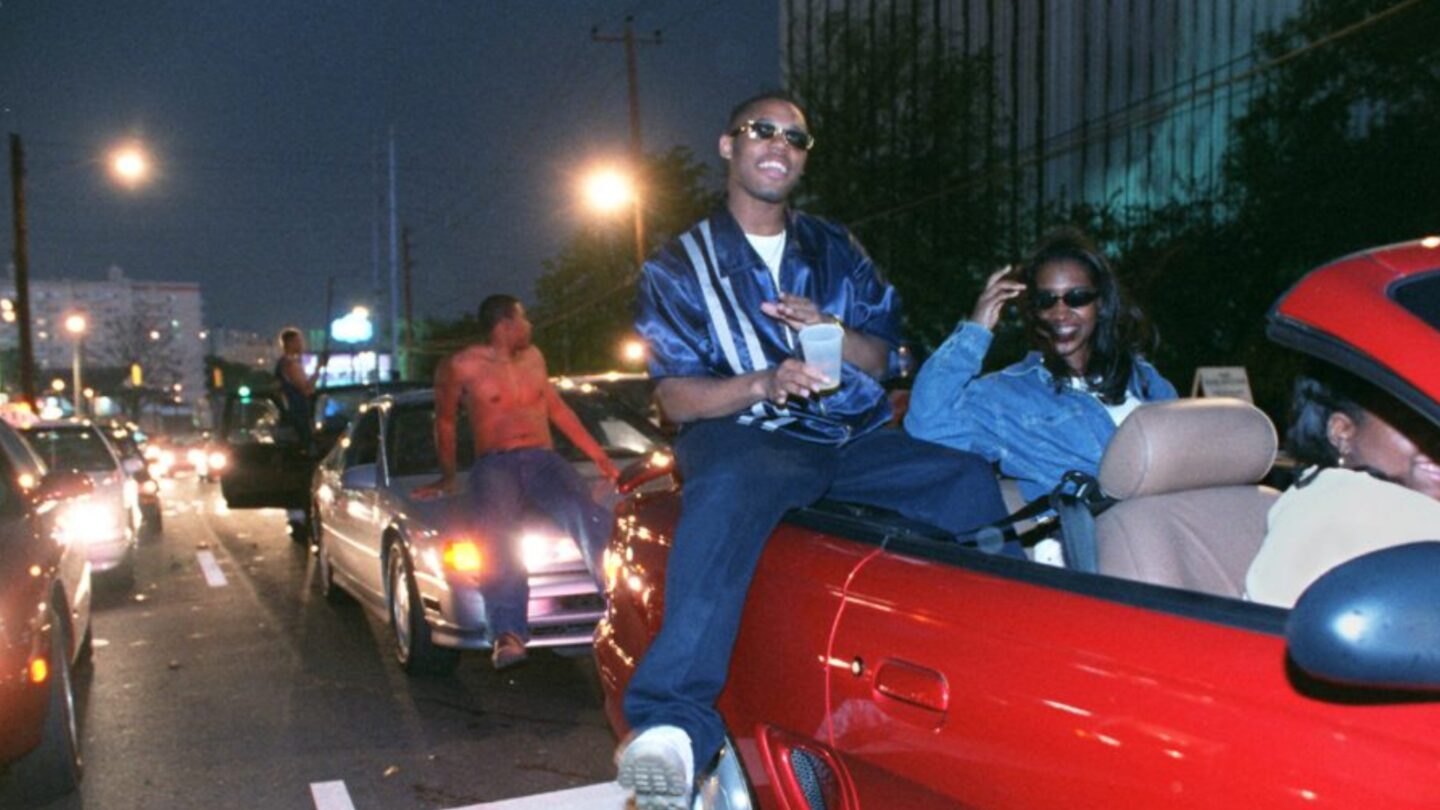

Freaknik became a party that spanned from festival grounds to Atlanta’s roads through cruising, according to Quiros.

“Cruising is the main way that revelers enjoy themselves which is essentially like sitting in cars and literally not moving, just [the] fun of listening to music,” she said. “This is before cellphones are big. People are passing camcorders from vehicle to vehicle, filming things, dancing on the hood of cars, sharing music.”

Hawthorne was a part of the Black College Spring Break Planning Committee that was created by Atlanta Mayor Bill Campbell to try to plan public safety aspects.

“I felt a sense of stewardship for the image of Atlanta, and I wanted to help organize what is the best we could you know in going through that time period. It was an unorganized event and had a lot of negative impacts in the city,” he said.

Atlanta was thrust into the spotlight nationally in the mid-‘90s following protests from city dwellers for “caving in to the opposition and fear of largely white, inner-city neighborhoods to the event,” according to the New York Times.

“It was coming to a point where Atlanta was perceived as not welcoming of African-American students,” Hawthorne said. “And I think that was definitely not what Atlanta wanted to portray as the home of the Atlanta University Center and a major social and civil rights movements that have come out of the area.”

Hawthorne decided to give the recommendation to Campbell to end Freaknik in Atlanta after learning about the thousands of crimes, including rape and indecent exposure, that were reported around the events.

Hawthorne is now advising Neal on the public safety aspects for the upcoming festival.

His suggestion?

A name change to rebrand the event.

“Twenty years ago in 1998, my objective was to get the freak out of Freaknik, because of that … whole aspect of this, the sexual side of this thing was what I think gave a black eye to the event and ultimately led to its demise,” he said.

‘Make It Peaceful’

Neal, who attended Freaknik on his own in 1996, said that he believes now is the prime time for the festival to come back to the city.

“This isn’t the first attempt but … I’m the only one that’s trying to bring it back and to make it as peaceful,” Neal said.

This year’s event will be confined just to the Lakewood Fairgrounds and will feature educational elements, such as health screenings provided by America Kinetics LLC onsite.

Already they have sold 7,500 tickets, according to Neal. He said his projections show the festival selling out by the first or second week of June.

The demographics of ticket holders skewed younger than what he predicted, he said. About 40 percent of them are between 25 and 35 years old, according to Neal.

“The fact that we’re keeping pace with the amount of excitement that these other festivals are, tells me that hey there is a real niche here of ’90s, early 2000 artists that, given the proper content and environment, people would love to go see and enjoy,” he said.

While there will be learning opportunities for Freaknik Festival attendees, Neal said that this is an adult, non-family-friendly event.

“I mean if I hear the word[s] family-friendly, I’m thinking I’m kids. I’m thinking fun. I’m thinking jumpy houses. I’m thinking you know juice stations and all that. That is not what this event is about,” he said.

Neal said that his event is about unifying the communities in Atlanta.

“If we can control it and make sure it is safe for attendees to attend, then I don’t think the Freaknik story has to end being a black eye in Atlanta’s history,” he said. “They can actually come out and be that great event for those who choose to partake in it and can enjoy for years to come.”