Hank Aaron Honored At Funeral In Atlanta: ‘Just His Presence … Changed This City’

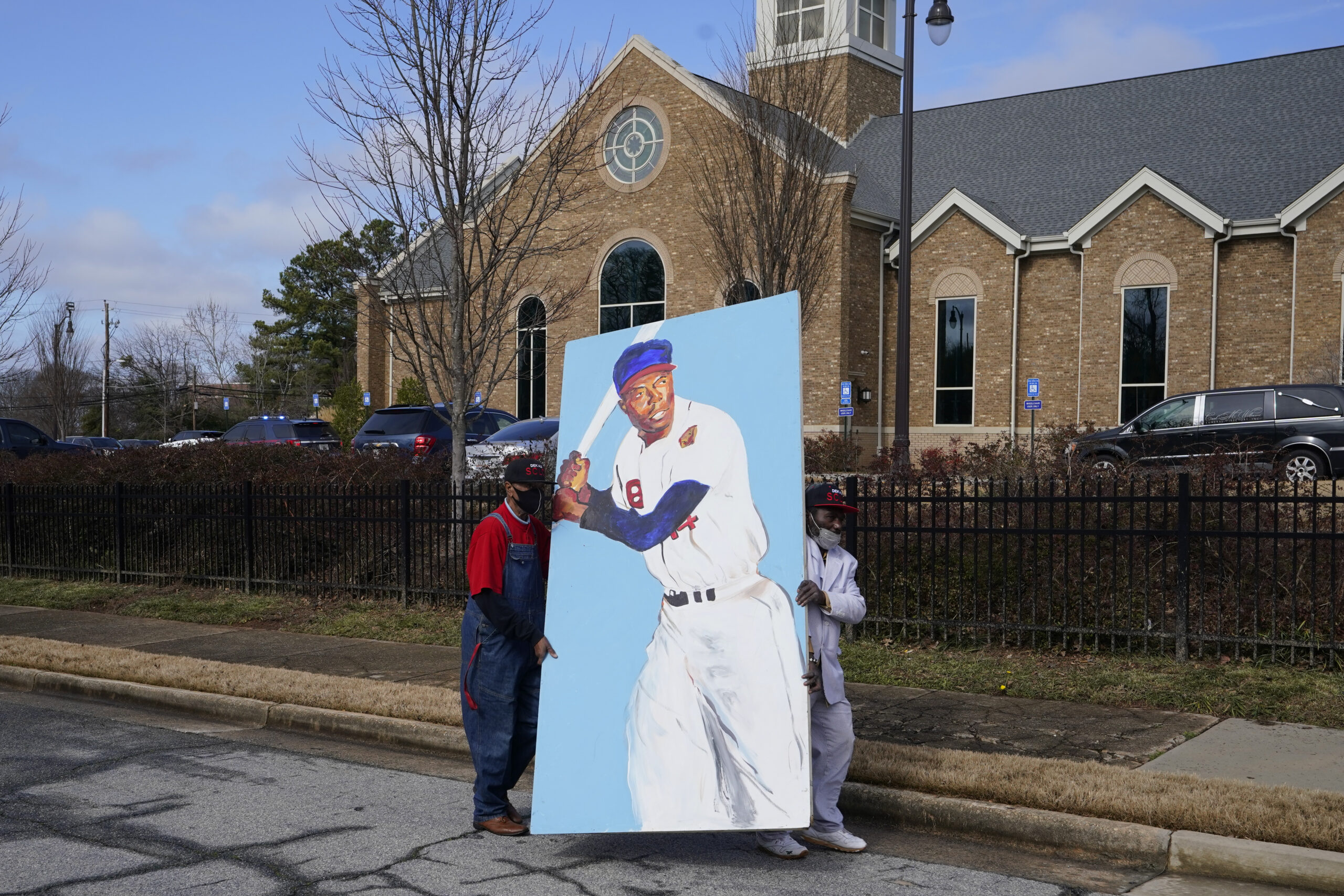

People arrive Wednesday with a painting of Hank Aaron as others attend the Baseball Hall of Famer’s funeral at Atlanta’s Friendship Baptist Church.

John Bazemore / Associated PRess

Former U.N. Ambassador and Atlanta Mayor Andrew Young remembered when Henry “Hank” Aaron came to Atlanta prior to the Braves’ first game in the city in 1966.

Young said he overheard a group of white men standing on the street watching Aaron riding in a convertible saying, “We got to be a big league city now.”

“Just his presence, before he hit a hit, changed this city,” said Young.

Aaron, one of the greatest sluggers in baseball history, died Friday of natural causes at 86.

At his funeral Wednesday afternoon at Friendship Baptist Church, Aaron’s casket rested in front of the pulpit, surrounded by flowers and a framed photo of Aaron in front of one of his statues.

“He was and is ‘the man,’” said Young. “And he did that without trying.”

Former President Bill Clinton called Wednesday’s service a “tribute to a consistent life.”

“The longer life went on for Hank Aaron, the more graceful he became,” said Clinton. “Grace is not the absence of anger or resentment. It is the conscience choice not to surrender to them. A choice every human being has to make every day.”

Clinton remembered when Aaron endorsed his run for president in 1992.

“And for the rest of his life, he never let me forget who was responsible for me winning,” said Clinton. “Hank Aaron never bragged about anything except carrying Georgia for me.”

“We’ve lost a good friend and a great athlete,” said former President Jimmy Carter in a recorded video statement.

The funeral took place in front of a small in-person gathering. Aaron’s wife Billye was thankful for the outpouring of remembrances of her husband, and for those who attended the service.

“We know that this pandemic has been horrific, but you chose today to brave the weather and take the risk, and I pray that you will continue to follow all of the guidance and instructions for wearing your masks and keeping yourselves safe,” she said.

Three of Aaron’s grandchildren — Victor Aaron Haydel, Emily Haydel and Raynal Aaron — took part in the service, reading scripture and quotes from their grandfather’s life.

Valerie Montgomery Rice, president and dean of Morehouse School of Medicine, spoke of the generosity of Hank and Billye Aaron, who have given more than $4 million to the school.

“While the financial gifts are important, it is his presence that has mattered. His presence, his smile and his nod,” said Rice. “While Mr. Aaron will be remembered for all the home runs he hit, his true legacy is seen in the lives he’s changed for the better. He used his gift to make a living and used the proceeds of that gift to make a life.”

Braves chairman Terry McGuirk and longtime sports broadcaster Bob Costas also shared their memories of Aaron.

Born one of seven children in Mobile, Alabama, in 1934, Aaron began playing semi-pro baseball at the age of 15. He had a brief stint with the Indianapolis Clowns in the Negro Leagues (and would later become the last Negro Leaguer still active in the game when he retired in 1976).

Aaron led the National League in hitting in only his third major league season. A year later, in 1957, he earned the league’s Most Valuable Player honor after hitting 44 home runs and driving in 132 runs. That year, he finished third in hitting behind Stan Musial and Willie Mays. Aaron batted .393 and three home runs in the World Series that year, leading the Braves past the New York Yankees.

Aaron’s final home run of the 1973 season put him within one of Babe Ruth’s all-time record of 714. It also left him an entire offseason to endure racist hate mail and death threats. He tied Ruth on Opening Day 1974 in Cincinnati. On April 8 of that year before a sellout crowd at Fulton County Stadium in Atlanta, Aaron hit his 715th career home run to pass Ruth.

Aaron rounded the bases to thunderous applause and fireworks that night. He was met at home plate by his teammates as well as his parents.

On Wednesday, former baseball commissioner Bud Selig, a friend of Aaron’s for more than 60 years, called the event a “powerful civil rights moment.”

“Only a person with his great inner strength and determination could overcome the kind of hate mail he did,” said Selig, who called Aaron “no doubt, the greatest player of our generation.”

“Henry was a man of grace, a man of patience, a man of tolerance, remarkable dignity under many tough situations,” said Selig.

He finished his career with 755 home runs, a record that stood for more than three decades.

“I stand here because God gave me a healthy body, a sound mind and talent,” Aaron said at his Hall of Fame induction in Cooperstown, New York, in 1982. “For 23 years, I took the talent that God gave me and developed it to the best of my ability.”

“It was not fame I sought,” said Aaron. “But rather to be the best baseball player that I could possibly be.”