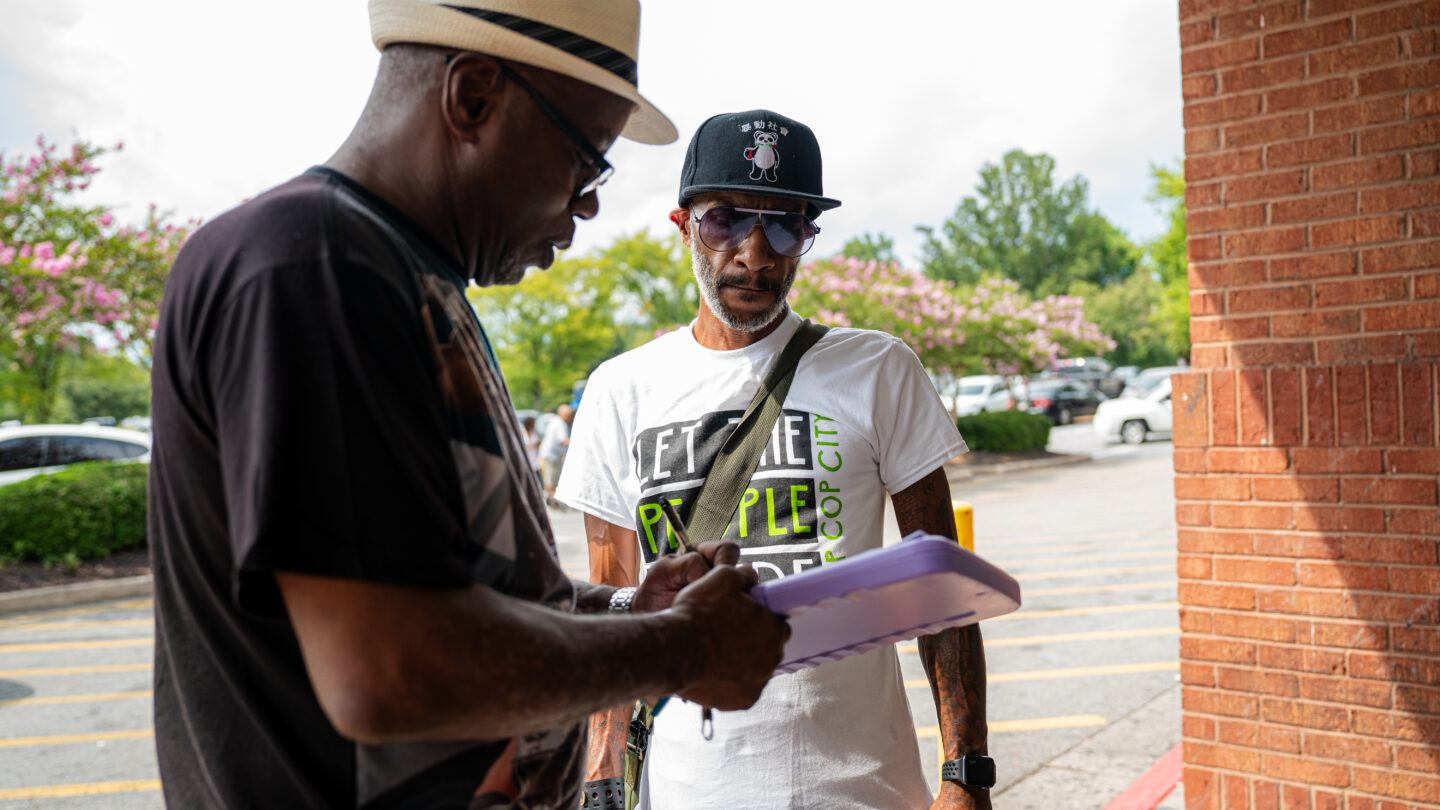

Opponents of an Atlanta police and fire training center exulted as they marched into City Hall in September with 16 boxes of petitions to force a referendum on the issue. “116,000 signatures — can you hear us now?” they asked, confident they had enough.

But an analysis by four news organizations finds the outcome — if city officials ever count the petitions — could be decided by a narrow margin.

Organizers of the monthslong petition drive to “Stop Cop City” still say they have 116,000 signatures, but a hand count by The Associated Press, Georgia Public Broadcasting, WABE and The Atlanta Journal-Constitution tallied only about 108,500.

The news organizations found nearly half of a statistical sample of 1,000 entries couldn’t be matched to an eligible registered city of Atlanta voter. Some signers live outside the city, some seemingly fabricated addresses, and others provided far too little information — like the “Jesus Christ” who signed with an address of “homeless.”

Even with those problems, the analysis finds it’s still statistically possible that organizers met their target of 58,231 signatures. But additional legal and procedural disputes could doom the effort by sharply shrinking the total of eligible signers.

The fight over the $90 million training center has become a national dispute, with opponents deriding a facility they say will worsen police militarization and harm the environment.

Kate Falanga, a bar manager who signed the petition, called the proposed project “awful” and said the land — part of a huge urban forest — should be used for something that’s “better for everyone.”

“There’s a lot better ways to spend that than on militarizing a police force which is already an incredible presence and seems kind of unnecessary,” Falanga said.

Supporters including Democratic Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens say the city must replace outdated facilities and better train officers to avoid improper use of force.

“I believe this center will be the classroom space that redefines how we approach policing and maintains the readiness of our first responders to address the challenges they face,” Dickens wrote in September to U.S. Sen. Raphael Warnock, after the Georgia Democrat questioned referendum procedures.

Both Dickens and city officials who would validate signatures declined repeated interview requests.

The ballot referendum seeks to cancel the city’s lease with the private Atlanta Police Foundation to build and run the 85-acre (34-hectare) complex.

“The people who signed those papers, they’re real, they exist,” said Britney Whaley, who helped organize the petition campaign. “They want to see it on the ballot. They’re not going away. We have enough signatures to transform politics in Atlanta.”

But not everyone who signed counts as eligible in the citizen-led petition process, and the referendum push is in legal limbo. The reporting partners set out to analyze petition entries because officials haven’t counted the 25,000-plus pages submitted to the Atlanta city clerk.

Petitioners were required to collect 58,231 signers. That’s equal to 15% of Atlanta’s active registered voters in 2021. Each eligible signer must also be a registered city voter now.

With about 108,500 entries, nearly 53.7% must be valid for organizers to be successful.

Overall, the analysis finds as many as 52.7% of entries could be eligible. That’s below the 53.7% threshold, but because the analysis is a sample, it has a margin of error of plus or minus 3.03% at a 95% confidence level. That means between 49.7% and 55.7% of entries should be valid. Thus, a complete count could produce enough valid entries to cross the threshold.

The reporting partners analyzed a sample of 1,000 entries, taking a random sample of pages proportionally from each of 16 boxes, and then choosing a random entry on each page. Comparing names and addresses to voter rolls, the partners matched 47.5% of names to eligible Atlanta voters.

Examples of invalid and undetermined signatures

Source: Atlanta Journal-Constitution analysis of petitions provided by Atlanta City Clerk’s Office | Credit: Pete Corson & Charles Minshew/The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Another 5.2% of entries are uncertain — for example, common names matching multiple voters, but without a matching address. Those might be found eligible using birth dates redacted from public petition copies, or through signature comparisons. They might also be found eligible if signers provide additional information, a process known as curing.

Conversely, birth dates and signatures might lead to some apparently eligible entries being disallowed. Signature comparison, in particular, has been a much-disputed part of the proposed verification process.

The news organizations didn’t attempt to verify signatures, which means they couldn’t detect fraudulent signatures made using a voter’s information. At least a handful of pages have signatures in what could be the same handwriting. The sample found no duplicate signatures, but was statistically unlikely to detect people who signed more than once. Dickens said that’s why the city must examine petitions if a referendum goes forward.

“We have a duty to review those petitions and ensure that it is Atlantans who are speaking for Atlanta,” the mayor wrote to Warnock.

Whaley said petition collectors wanted anyone possibly eligible to sign.

“Now, you may be a little fuzzy on some details, right?” she said. “But what I won’t do is let you walk away without signing my paper if there is any chance that you were registered in the city of Atlanta in 2021.”

The demographics of eligible petition signers closely match that of the city’s electorate: roughly 50% Black, a third white and a majority age 42 or younger.

But people living near the training center site, which is just beyond the city’s eastern border, were more likely to sign the petition. The five city ZIP codes nearest the site contain less than a quarter of Atlanta’s registered voters, but produced 37.6% of eligible sampled entries.

By contrast, only 4% of eligible sampled entries came from ZIP codes in the city’s northern Buckhead region, where the electorate is whiter and more politically conservative.

Many of the people found ineligible in the analysis are not currently living within Atlanta. The media partners found 16.8% of petition signers registered elsewhere in Georgia, sometimes steps outside the city limits. Others were not Atlanta voters in either 2021 or 2023 or appeared to not be registered to vote at all.

Another 30% of entries that appear eligible could be disqualified for legal reasons or by city counting methods.

Former City Clerk Forris Webb, who would lead any signature verification, declines to say how the city will treat entries that don’t have an address matching voter registration rolls. That alone could disqualify 12% of potentially eligible entries.

State law says the collectors witnessing signatures must be registered Atlanta voters and that organizers had until Aug. 21 to submit petitions. A federal judge extended that deadline into September and ruled that people who live outside the city could witness signatures. The 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals paused enforcement of that order. That’s why the city refused to count the petitions when organizers turned in boxes on Sept. 11.

Even if petitions are ultimately counted, only entries before Aug. 21 and collected by Atlanta residents might be ruled valid. The two issues could disqualify 20% of potentially eligible sampled entries — likely defeating the effort.

Appellate judges will hear arguments on the deadline and petition witness issues Thursday. The city also argues the underlying petition is void because it violates state law and would illegally cancel a contract.

Whaley said city officials act as if they are “scared,” calling their actions to block the referendum “deeply problematic and undemocratic.”

“I think now it is at a point where they are doing anything in their power to try to save this project,” she said.

R.J. Rico of The Associated Press; Amanda Andrews of Georgia Public Broadcasting; Chamian Cruz, Emily Wu Pearson and Jasmine Robinson of WABE; and Riley Bunch, Pete Corson, Rahul Deshpande, Stephanie Lamm, Charles Minshew and Justin Price of The Atlanta Journal-Constitution contributed to this report.