The normally quiet community of Brunswick, Ga., has been rocked by the fallout of the shooting death of a 25-year-old black man, Ahmaud Arbery, who was chased and shot by two white men while jogging in February, according to a viral video of the incident.

The coastal city has largely escaped major racial protests or riots, but outrage about Arbery’s death has sparked conversations about corruption in the criminal justice system and racism out into the open in an unprecedented way.

“It is the most horrifying display of hatred that I know personally I’ve ever seen, but this community has ever displayed,” said Glynn County Commissioner Allen Booker. “That’s been recorded.”

Booker, the only black member of the commission, represents most of the county’s African American community, 27% of the population. And his nephew’s best friend was Ahmaud Arbery.

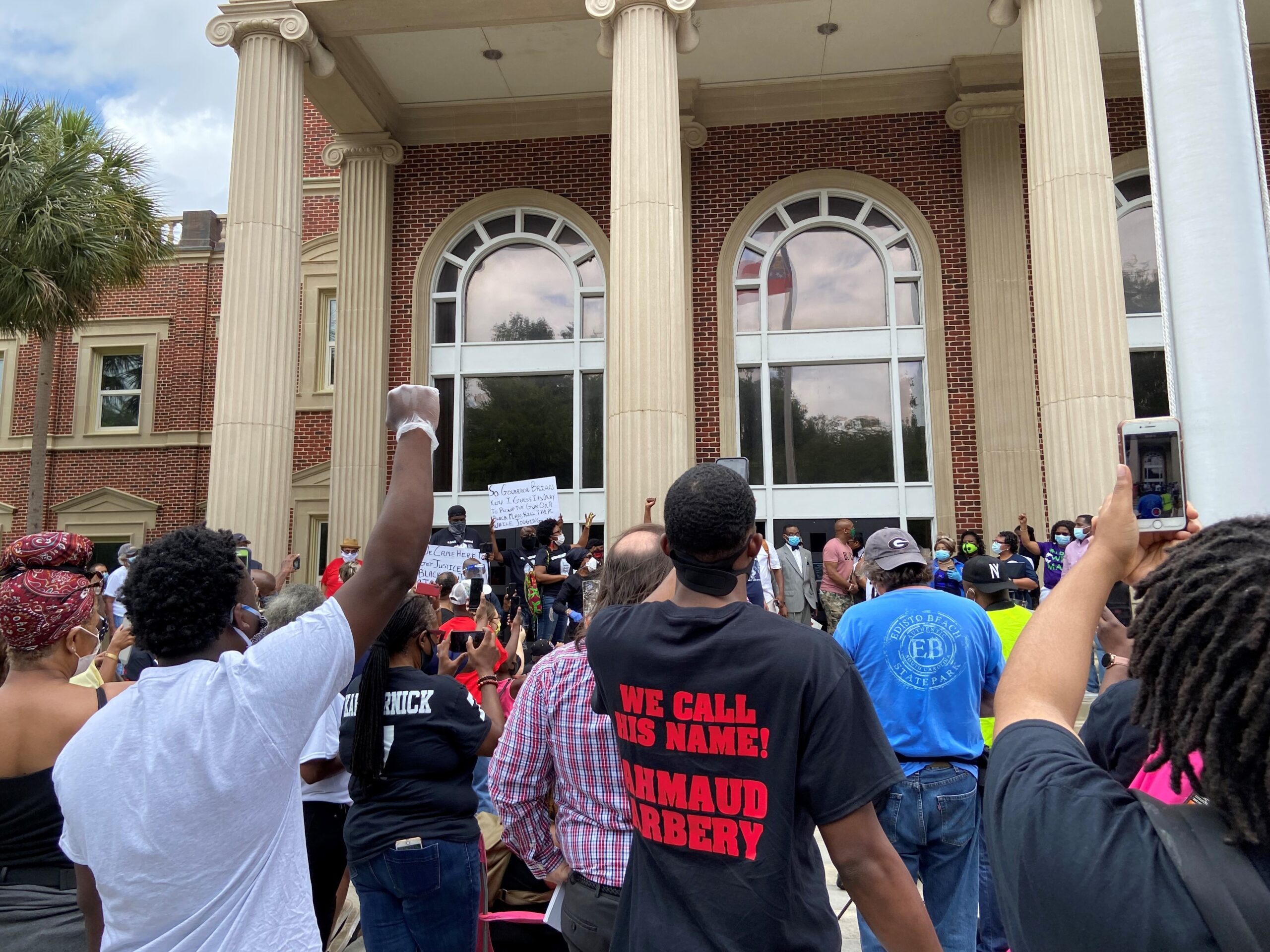

“As I sit here and I look at you all, I see the beginning of the great awakening,” said Brunswick NAACP President John Perry to hundreds of people gathered on a recent Saturday at the county courthouse, which has become the location for many Arbery-related protests. This particular rally was organized by a coalition of groups, including the ACLU.

“An awakening that acknowledges that there’s been a lot of darkness for a long, long time. But Ahmaud’s death sounded off an alarm,” Perry said. “We’ve got to wake up right now and we’ve got to demand of our justice system to be to us what it promised to be.”

Unlike many southern cities, Brunswick hasn’t seen violence, riots or major protests about race, Booker said.

In the 1960s, black and white leaders compromised. Schools integrated here before the rest of the state was forced to.

“I remember hearing the story of when the Klan had planned to march here, they were met at the county line by a diverse group of well-armed men,” Booker said.

Instead, hate was “undercover,” he said. Until the viral video of Arbery’s killing, which has thrust it into view.

Daily Indignities

“I think some folks feel that this could be the cathartic moment,” said Dante Hudson, who worked as a public defender in Glynn for six years until 2012. He was one of a handful of black attorneys in the area at that time and agreed this case has exposed racial tensions in the community.

“We’ve kind of been dealing with this for quite some time; no one has really said anything, but this is sort of the straw that broke the camel’s back.”

Hudson said the circumstances of Arbery’s death were not surprising to him, in part because, he said, they reflect how relationships drive the criminal justice system in a small town like Brunswick. He saw local lawyers, who knew judges and prosecutors, get better deals for their clients.

Attorneys for Arbery’s family allege this dynamic played a role in Arbery’s case too. Gregory McMichael, one of the men charged with Arbery’s murder, with his son Travis, is a former police officer and former investigator in the local district attorney’s office. The two were not arrested for months, despite being found at the crime scene with guns.

Hudson, who now works in Atlanta, said he enjoyed living in Brunswick. But while it was difficult to work in the system without local connections as an out-of-town lawyer, he said, it was even more so for black lawyers.

“For African Americans, it’s really just a tough place to live, and to work, and to be successful,” he said. “It was a lot to sort of breakthrough that caste system, the caste system legally. And it was very helpful, if you were white. It was more of a challenge being black.”

Today, there is just one practicing black lawyer based in Glynn County, according to James Yancey. And it’s him. He’s been here for three decades.

“I’ve talked to a few black lawyers who were born and raised here,” Yancey said. “But they say, ‘Look I’m not coming back down there. Nope.’ ”

Yancey attributed it in part to the “daily indignities” black people in Glynn, and across the country have to face. But the reputation of the Deep South in particular, he said, keeps some people of color away.

“I often tell some of my white brothers and sisters, I say yeah, ‘I’m a lawyer … But we generally live in two different worlds,’ ” he said. “We may walk down the same street. We may worship in the same church, go to the same school, but we live in different worlds.”

Those worlds are now under scrutiny, pulling back the curtain on some of those “indignities.”

A 2017 video shows an interaction Arbery had with police. He was sitting in his car in a park. Police suspected him of doing drugs and confronted him. They ultimately force him to his knees, try to tase him, and Arbery accuses them of harassing him.

“I got one day off a week,” Arbery said. “One day. One day off a week. I’m trying to chill on my day off. I’m up early in the morning, trying to chill.”

“Now I’m on my knees for nothing. On my day off,” he said, before being let go.

An Opportunity

There are no black prosecutors in the Glynn County district attorney’s office, no sitting black judges and the county police department has been criticized for its lack of diversity.

The Arbery shooting has prompted a wave of political activism and calls for new candidates in local elections like district attorney, which has been unopposed for decades.

John Richards, one of the organizers of the #IRunWithMaud movement started by Arbery’s closest friends said “raising up viable candidates for local offices” is one of their long-term goals.

“There’s an old-guard mentality in some instances to local public service and office,” he said.

“We’re guilty too,” said Perry, with the Brunswick NAACP at the rally. “We will not be on trial for the bullet shot. But we are on trial for every moment we heard of corruption. But since it did not ffect us, we turned our head too.”

“But today, this declares the awakening,” Perry said.

With this new tension in the community, Commissioner Booker still has hope for his hometown.

“There’s enough good people that are committed to change; real change, to make that happen,” he said. “But we do need the world to keep the pressure and the spotlight on us. Because we do have a lot to clean up.”

State investigators and the U.S. Justice Department are continuing to look into the case.

For a deeper exploration of Ahmaud Arbery’s story, listen to WABE’s podcast, “Buried Truths.” Hosted by journalist, professor, and Pulitzer-prize-winning author Hank Klibanoff, season three of “Buried Truths” explores the Arbery murder and its direct ties to racially motivated murders of the past in Georgia.