When the World Health Organization declared monkeypox a public health emergency over the weekend, it also warned of another threat to society:

“Stigma and discrimination can be as dangerous as any virus,” said WHO Director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

In fact, the WHO emergency committee that had previously considered whether to issue such a declaration was unable to reach a consensus in part because of concerns about the risk of stigma, marginalization and discrimination against the communities hit hardest by the virus.

The global monkeypox outbreak appears to mostly affect men who have sex with other men.

A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that 98% of people diagnosed with the virus between April and June in more than a dozen countries identify as gay or bisexual men, and the WHO says that 99% of U.S. cases are related to male-to-male sexual contact.

That means that the public health systems can target their messaging and interventions to the specific communities most at risk. But it also carries the risk of stigmatizing those populations, while sowing complacency in others that could still be vulnerable.

Public health experts stress that monkeypox is relevant to everyone, since it can spread through skin-to-skin contact and potentially contaminated objects like clothing or towels. And viruses can infect anyone.

The U.S. has already documented two cases of monkeypox in children, for example.

“While we may be seeing clusters primarily in certain groups of people, viruses do not discriminate by race, by religion, or by sexual orientation,” infectious disease researcher Dr. Boghuma Titanji told NPR.

How exactly can leaders educate people about monkeypox without stigmatizing those who are most likely to be affected by it?

At a Tuesday briefing, White House adviser Dr. Ashish Jha urged people not to “use this moment to propagate homophobic or transphobic messaging,” instead encouraging them to stick to evidence and facts, and to do so respectfully.

Steven Thrasher, a writer and professor at Northwestern’s Medill School of Journalism, says part of the solution is having adequate resources in place for testing, vaccinating and supporting people when they’re diagnosed (the U.S. has been criticized for its limited supply of vaccines, but is expected to make more available in the coming weeks). Another part is tackling homophobia itself.

“Because as long as there is a homophobic society and people are afraid of what it means to come forward, that this thing will make people think that they’re gay, then they’re not going to want to come forward,” Thrasher told NPR last month.

“And there’s no easy fix for that. That’s a long-term problem that needs long-term thinking to undo and make different.”

How to think about risks and be proactive

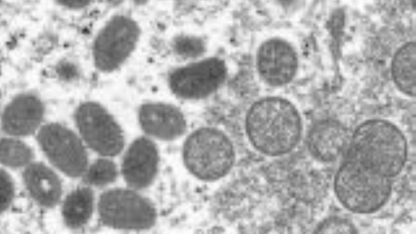

The monkeypox virus is similar to smallpox and endemic to Africa — nearly all cases previously found outside the continent were tied to international travel and imported animals.

What’s different now is how well it spreads through intimate person-to-person contact, says Jason Cianciotto, a vice president of Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

“But it doesn’t necessarily have to be sexual: cuddling, massage, sharing bedding or towels that have come in contact with pustules,” he told NPR’s “Weekend Edition“. “Even if you’re fully clothed, if you’re on the dance floor or dancing close to someone, there is the possibility of transmission.”

Dr. Ali Khan, a former official of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who worked on previous monkeypox outbreaks in Indiana and the Democratic Republic of Congo, says about 95% of infections are transmitted by sexual contact.

He tells “Morning Edition” that the fact that the outbreak is most concentrated among men who have sex with men provides a good opportunity for prevention activities within this group, which has been proactive about getting information and lining up for vaccinations.

“But there is the reminder that people who are not amongst this group are at risk, and we need to be concerned — not panicked, but concerned — and make sure that we do adequately prevent this infection from continuing to spread,” he says. Khan added that public health data plays a crucial role in identifying cases, treating individuals, vaccinating close contact ((contacts?)) and slowing the spread.

There were 3,487 confirmed cases reported in the U.S. as of Monday. And as Cianciotto notes, a rise in cases doesn’t just mean that more people are at risk — it could mean that more vulnerable people are at risk.

“I’m really concerned that if the monkeypox outbreak goes unchecked, that it, too, will concentrate among low-income communities of color where HIV and COVID-19 is concentrating among immigrants, particularly those undocumented who are afraid to access health care,” he said. “And that would be a tragedy.”

Why stigma is dangerous, and how to combat it

Titanji, the clinical researcher, says it’s dangerous for public health messaging to falsely suggest that monkeypox is not an issue of concern to anyone other than men who have sex with men.

That’s in part because it breeds stigma, which could prevent infected people from coming forward, seeking care and alerting their close contacts.

“When we are trying to contain an outbreak, what we want … is people to seek medical care when they see suspected lesions, so that they can be tested and be offered the treatment they need,” she says.

She adds that most people won’t need to be hospitalized for treatment, since many tend to recover with supportive care, hydration and isolation. (The CDC says more than 99% of patients can expect to survive, though some researchers worry monkeypox could mutate and become more dangerous).

Failure to address stigma early on can also create a sense of complacency in other segments of the population who may not otherwise be paying attention to the public health emergency, Titanji adds.

She says it’s important for public health officials to act early, and offer messaging that is not only clear but can also earn and restore the public’s trust.

For her personally, that involves sticking to facts, acknowledging unknowns and being clear that information may change as the science evolves.

Cianciotto says there are three main pieces of information he would like to share with men who have sex with men.

“The first is to be aware, but don’t panic,” he says. “The second is that if they have flu-like symptoms or start to see a rash, to seek medical attention and stay home, right? And the third is just to care for each other, right? And that’s what the second thing is about — knowing and understanding, just like we did for COVID-19. If we don’t feel well, don’t go out, get the help that we need and care for and educate each other.”

What the HIV/AIDS response can teach us

Public health experts and advocates are looking back at the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s and 1990s as an example of what not to do.

Titanji explains that because some of the first cases of HIV were identified in gay men, it was quickly — and inaccurately — labeled “a gay disease.”

The stigma and blame kept many people hidden in shame, causing pain and suffering in the LGBTQ community. It also meant that public health officials didn’t channel the appropriate resources into addressing the outbreak when it first began.

“In hindsight, we know that the impacts of that stigma that was present in the early days of the HIV response lingered for multiple years later on, and we have essentially been playing catch-up to destigmatize HIV since that time,” Titanji says, adding that she sees parallels with the monkeypox outbreak today.

Cianciotto, of Gay Men’s Health Crisis, says one of the most important takeaways from the HIV/AIDS crisis is the value of a sex-positive approach to education.

He points to New York City, where thousands of appointments for monkeypox vaccines filled up within a matter of hours, as proof that people in these vulnerable groups will take appropriate precautions if given the right information.

“We are not going to end HIV, and we’re certainly not going to curtail the monkeypox epidemic, by trying to shame people into not having sex or only having certain types of sex with certain people,” he adds. “When you equip people with the information they need to make healthy choices for themselves and for their community, and when you help them approach those decisions with self-love and acceptance, it’s amazing what the community is able to achieve.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))