Atlanta’s air is getting cleaner. Earlier this month, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency made it official: The metro area is now in compliance with federal standards on ozone, which contributes to smog.

Like us on Facebook

That’s good news for people’s health, but the pollution rules could be stricter. The Trump Administration recently delayed fully implementing a lower ozone standard. Still, officials here say it’s a big deal that Atlanta is meeting federal ozone rules.

“[It’s] a real affirmation that air quality in Georgia and Atlanta is getting better and better,” said Karen Hays, chief of the air branch at the state Environmental Protection Division. “Certainly the population of Georgia is increasing and Atlanta is increasing and the economy is getting better and we’re driving more vehicles. Despite all those things happening, our air is getting cleaner.”

Ozone comes from car and truck tailpipes and from industrial sources, like power plants and factories. But not directly. It’s a product of the emissions from those sources reacting with sunlight. Chemical compounds from trees and plants can contribute, too.

Meeting The Standard

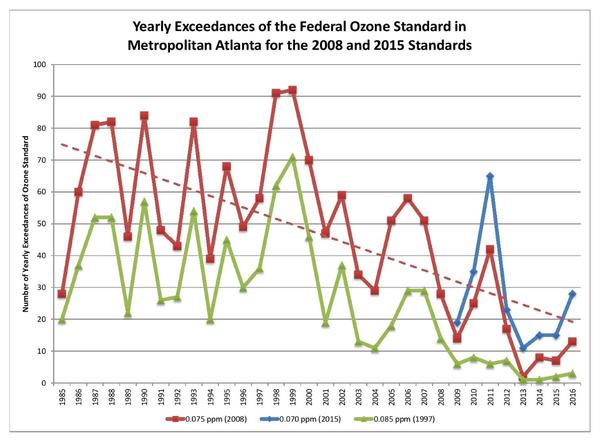

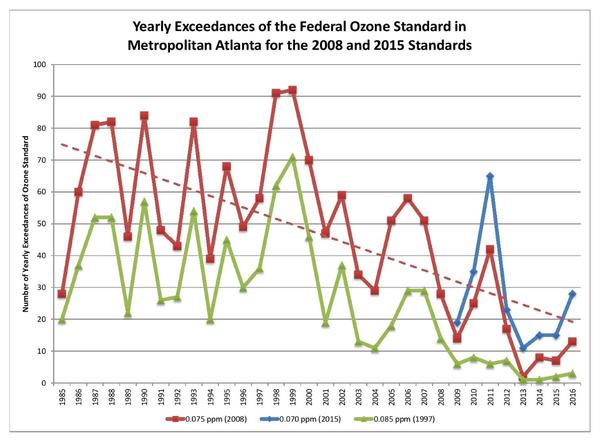

In the 1990s, Atlanta would violate ozone standards around 90 days a year, said David D’Onofrio, the air quality and climate change planner for the Atlanta Regional Commission. The metro area has made a lot of progress since then.

“Part of it is the fact that power plants have been getting cleaner in our region,” he said. “Part of it is related to technology on cars. Cars are producing less pollution themselves. The fuel they’re burning is cleaner. They have higher miles per gallon.”

Atlanta just met ozone requirements set by the EPA in 2008. The agency released lower ozone standards in 2015, but the Trump Administration announced earlier this month that it is putting off designating which parts of the country are out of compliance with the stricter rule.

“From a scientific standpoint, I’m happy we’re hitting the old standard, but I’d like to see us approaching the new standard, and even below,” said Jeremy Sarnat, associate professor of environmental health at Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health.

Health Effects

The science on ozone is strong, Sarnat said. Ozone can aggravate lung and heart problems. Children, seniors and people with pre-existing conditions are most at risk from it, but ozone can even take a toll on people who are otherwise healthy. And as research on the health effects of ozone continues, said Sarnat, scientists’ recommendations on exposure keep coming down.

And ozone affects everyone in a region; it’s not the kind of pollutant that sticks right next to the highways, for instance.

“We’re all exposed to the ambient air,” said Christina Fuller, an environmental health professor at Georgia State.

Still, some people are more susceptible than others.

“When you add poor air quality to populations that already have other effects, then you get that much worse,” said Stephanie Miles-Richardson, who directs the Master of Public Health program at the Morehouse School of Medicine.

Pollution doesn’t exist in a vacuum. People who live in neighborhoods near highways or industrial sites are affected by other air pollutants, too.

Plus, it’s not always a choice for people to not go outdoors during a smog alert.

“Maybe walking to the bus stops, things like that,” said Miles-Richardson. “So while we’re all impacted by poor air quality, there is a differential impact based on social determinants, based on preexisting health.”

The EPA said it’s delaying designating places that aren’t complying with the 2015 standard to give states more time to develop their air quality plans and so that it can review some scientific issues.

“The outcome of having a delay in putting into place those more stringent standards is that there will be higher levels in the air for longer periods of time. That’s going to increase the adverse effects of exposure,” said Fuller. “That’s a large burden on public health.”

No More Low-Hanging Fruit

It won’t be easy to continue reducing ozone in the Atlanta area.

“The low-hanging fruit is long gone,” Hays said. “We focus on the products of combustion, and that has really declined over the years, dramatically.”

In Atlanta more than 80 percent of that kind of pollution—nitrous oxides, or NOx—comes from sources like cars, trucks, construction equipment and trains, said Hays.

“That’s the really big challenge for us right now,” she said. “It’s really vehicle traffic that’s driving our ozone challenges.”

And fixing Atlanta’s traffic is a whole other ball of wax.

“Transit is a really important way to help reduce emissions, but improving the technology on cars is going to be a key driver to reducing ozone concentrations in the next few decades in our region,” D’Onofrio said.

Trump is reviewing federal car fuel efficiency standards, with the goal of rolling them back. He is also rolling back an Obama-era climate rule, known as the Clean Power Plan. That focused on the greenhouse gas emissions that contribute to climate change, but Emory’s Sarnat said that closing coal-fired power plants, which is what the Clean Power Plan would have done, would have helped lower ozone levels nationally.

For Atlanta to comply with the stricter ozone standards, it’s going to take more than local responses, Sarnat said.

“Some of the precursors to ozone formation are not originating locally. So they’re not coming from Atlanta emissions or in some cases even from Georgia emissions,” he said.

Sarnat said he’d like to see international cooperation on ozone.

“We have no chance if we’re going it alone,” he said.

For now, the 2015 standard will go into full effect next year. And a handful of Atlanta counties will probably have more work to do to meet it.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))