Georgia is rich in fireflies. At least 15 different species occur in Atlanta alone. Dozens more live around the state.

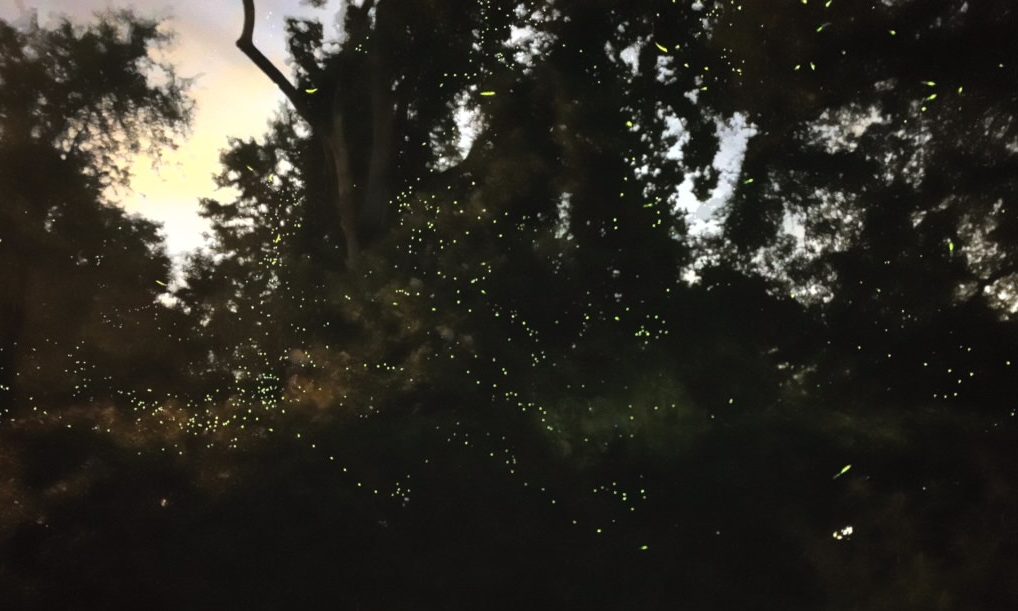

Beyond the familiar big dipper fireflies — those are the ones that people have fond childhood memories of, coming out around dusk, the males flashing their yellow lights while they hover in the yard – there are fireflies in Atlanta that glitter after dark in the treetops; there are synchronous fireflies here that flash together; and a species that hovers just above the ground, glowing continuously, rather than blinking at all.

While some people may feel they see fewer fireflies than they used to, for the most part, scientists don’t actually know how firefly populations are doing.

A community science initiative this summer, the Atlanta Firefly Project, aims to help figure out which places are good for fireflies, which are bad and how what humans do affects the insects.

“Does what we do matter?” said Kelly Ridenhour, who’s leading the research as a master’s student at the University of Georgia.

She’s spending most of her evenings these days out in parks, counting flashes as fireflies light up. She’s inviting the public to help, too, collecting counts from people watching for fireflies in their own yards or parks.

One evening earlier this month, she stood on a hill, looking out over a damp meadow, watching as the fireflies started to sparkle across the view.

“I mean they make their own light, what’s cooler than that?” she said.

Firefly Mysteries

On the whole, big dipper fireflies appear to still be common. A recent assessment by the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation found that they’re not at risk of extinction.

But Ridenhour said if people feel like they’re seeing fewer of them in certain areas than they used to, that matters, too.

“If we do push these culturally important nature experiences out of the city, where we can no longer catch fireflies or the majority of people can no longer catch fireflies in their backyard, even though that species is OK in the wild, it’s a loss for us,” she said.

Habitat loss, pesticides, lawn fertilizers and artificial light could all affect fireflies, Ridenhour said. (Children running around on summer evenings catching them is OK, she said, as long as they let them go again quickly.)

But for many species – there are more than 2,000 firefly species around the world – there’s very little information about their populations and how or if they’ve changed.

The Xerces Society assessment found 14 species of fireflies in North America that are at risk of extinction, but it found many more that there simply wasn’t enough information on to make any kind of judgment on their health.

“Nearly half of the species that we assessed came up as data deficient,” said Sarina Jepsen, endangered species program director at the Xerces Society. “Essentially, we don’t know enough about them to even evaluate the level of extinction risk that they face.”

Jepsen said in the past, a lot of the scientific research on fireflies has focused on their ability to light up – how it evolved, and how it could be used. But there has been limited research on how fireflies themselves are doing – something she says she hopes to see change.

It’s a knowledge gap that Lynn Faust said she’s seen, too.

She wrote the field guide on fireflies in the Southeast. When she began her work, she said, most of what she could find in the library about the insects was in the children’s section.

The reason for the lack of information, Faust said, is that fireflies aren’t a nuisance.

“Because they are not a public health problem, they don’t cause disease, and they’re not an agricultural pest, there’s very little grant money for universities to study them,” she said.

But, Faust said, fireflies are charismatic, offering a way to bring people into the world of insects.

“People are not afraid of them, and they kind of like them,” she said. “They’re usually associated with warm, fuzzy memories of childhood.”

That makes Ridenhour’s project to recruit people to help count them a popular one. She said she has volunteers across the city signed up to count firefly flashes.

“Most people are enthusiastic to get involved watching fireflies, and it’s something anyone can do,” she said.

How To Participate

It’s not too late to sign up for the project – she said her aim is to have all volunteers count a couple times in June and July.

The website for the Atlanta Firefly Project has instructions on how to participate; volunteers will need to have a smartphone to upload their information.

Ridenhour said she won’t be able to tell how specific firefly species are faring from one summer of research, though maybe over the long-term, she’ll gather enough data to do that work, too.

Instead, her focus is on how places are managed – how often they are mowed, what pesticide and insecticide use is like, proximity to artificial outdoor light at night – and how all that relates to the number of fireflies, or if they’re present at all. She said even if a volunteer sees no fireflies when they go out to count, that’s valuable information, too.

“Cities are actually great places to do this work because those pressures are often the greatest in city areas,” she said.

For people without yards, or who want to look farther afield, Ridenhour suggests looking for fireflies in places where woods meet an open area, and near creeks.

“Your nearby park is probably going to have some,” she said.

To be really prepared, Faust suggests scouting out a spot to watch during daylight hours, so that you don’t find yourself stumbling in the dark.

“You don’t want to show up in the dark at an unfamiliar place and then bumble off and get lost or get hurt,” she said.

And, she said, use a flashlight only minimally. Nighttime light can interfere with firefly’s ability to find each other – the flashes are how the males and females communicate with each other.

There are a couple other community science projects focused on fireflies. Mass Audubon runs Firefly Watch, a North America-wide program, and the community science app iNaturalist collects firefly observations.

For Georgians looking to branch out into other insect-counting projects, the third annual Great Georgia Pollinator Census is scheduled for late August.