Each summer, metro Atlanta school districts distribute free meals to students through a federal program started in 1975. Although the plan is federally funded, it’s distributed locally by schools, non-profits and faith-based organizations. During the pandemic, Congress issued waivers that made the program more flexible.

“What we’ve seen through this is incredible innovations through summer meal programs that allowed ‘Grab and Go’ meals to be served, allowed parents to pick up bulk meals, created incredible flexibility with the types of meals that were able to be served and how parents and kids were able to access those meals during the school year,” says Lucy Coady, the director of the No Kid Hungry Campaign.

The waivers will expire on June 30 if Congress doesn’t renew them. Some senators have introduced a bill that would do that, but it seems to have stalled.

“We are in absolute limbo,” Coady says. “At this point, we are waiting on Congress to take action and to prioritize this issue and give it the urgency. Every single day that passes is another day that school nutrition providers across this country have more uncertainty and more fear about what the school year is going to look like.”

That’s what nutrition directors like Alyssia Wright are trying to figure out. Wright is the Executive Director of School Nutrition for the Fulton County Schools. She says this year’s summer meals program isn’t as robust as last summer’s.

“Last year, we were open in over 50 sites and all those sites were free and open to the community and the neighboring students within the community for the entire summer,” Wright says.

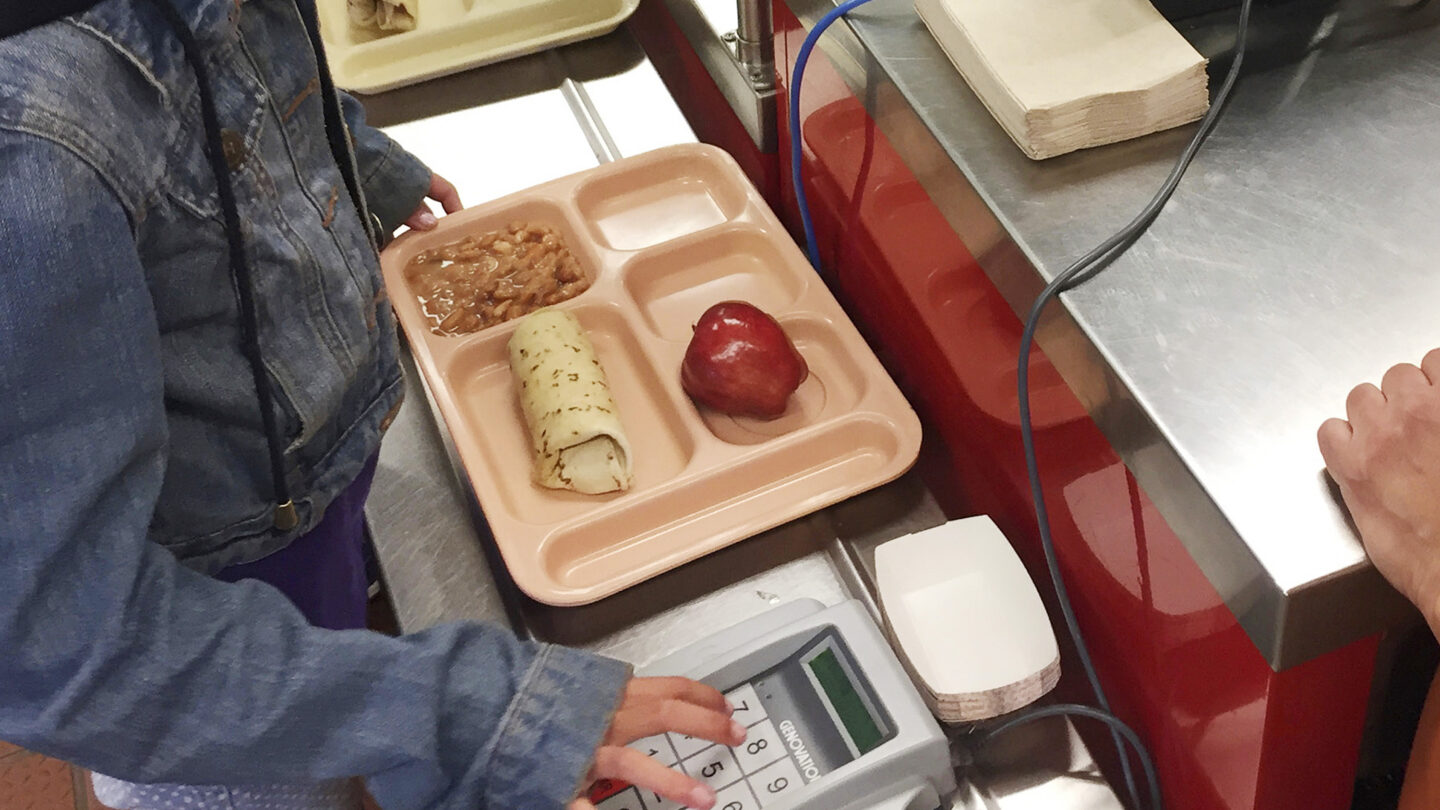

This year, the district has 30 sites and only students can receive meals. If the waivers expire, Wright says, the way Fulton can distribute food would change.

“Instead of the parent just coming in and picking up the meal or the student coming and picking up the meal … and taking it home, that meal after July 1 would have to be eaten on-site,” she says.

Coady says those kinds of restrictions kept some sites from opening at all this year.

“It’s going to lead to hungry kids this summer, and there is no question we are seeing it in real-time right now,” she says.

Metro Atlanta districts have been bracing for the end of the waivers and many are doing what they can to offer as many meals as possible. Fulton County and Atlanta Public Schools, for example, are partnering with non-profits to offer more food options for students. Meals are free for students ages 18 years and under and special needs students under 21. Sites are posted on district websites and social media platforms.

Wright says families can also use the FoodFinder app, created by a graduate of the Gwinnett County School District, to locate sites close to them.

Meantime, nutrition departments are trying to plan for the upcoming school year in the midst of rising prices and supply chain problems. The waivers made meals free for every student, regardless of income. But if Congress doesn’t act, about 10 million U.S. students could have to start paying for meals again in the fall.

“It’s a crisis,” Coady says. “I think parents see it. They see the impact of the supply chain when menus are changing on a daily basis, and [if Congress doesn’t act] it’s just going to get a lot worse.”