Communities in South Georgia are cleaning up from Tropical Storm Debby. But climate change is also affecting regular rain storms, giving them the potential to drop more water and create big problems for local governments.

Cobb County recently tabled a vote on a fee that would have helped fund repairs on aging water infrastructure. The county was trying to address the increase of flooding and failing pipes. Despite the growing need for repairs, officials aren’t sure how they’ll pay for pipe maintenance.

“We are getting more and more flooding complaints,” said Judy Jones, deputy director of Cobb County’s water system.

Flooding from storms is a growing problem as Cobb continues to develop and climate change intensifies and makes storms wetter. Jones said Cobb residents are seeing the county’s major creeks overflow into yards and roads more often than they used to. In the past few weeks, heavy rains and flash floods have inundated homes in the county.

As storms dump more rain, the infrastructure designed to handle all that water is struggling to keep up with demands as pipes are reaching the end of their lives.

“They’re starting to fail,” Jones said.

In October 2022, Cobb saw a backlog of 120 needed pipe repairs, Jones said. The county has completed 80 of them — over half of what they started with. But in the meantime, another 46 came up.

“We really need additional funding for pipe repairs; we’re not keeping up with pipe repairs,” Jones said.

She said right now the annual budget for stormwater is $8.5 million, and it can’t cover fixing all the pipes, much less any proactive projects.

So, Cobb came up with a plan to charge people based on how much their property contributes to stormwater problems.

It’s not a new system, as other parts of metro Atlanta already generate money this way for storm infrastructure, including DeKalb and Gwinnett Counties and the cities of Decatur, Roswell and Duluth.

Katherine Gurd, a project administrator with the Gwinnett County Department of Water Resources, said this type of fee structure, called a stormwater utility, has worked there for a long time.

“Gwinnett has had a stormwater utility since 2006,” Gurd said, “and since that time, there’s only been an increase of impervious surface in the county.”

She said when rain falls on natural areas, like dirt or grass, it soaks into the ground. But when rain hits hard human-made surfaces, it can cause runoff and lead to flooding or erosion in the community.

“Every driveway, every sidewalk, every parking lot, every building that’s put in, it generates impervious surface,” Gurd said.

Gwinnett manages this by having residents pay a stormwater fee based on square footage of impervious surface on their property.

Gurd said the stormwater utility is a steady revenue stream. As Gwinnett grows and gets more impervious surfaces, it’s also getting more money to adapt to that change — for example keeping up with pipe maintenance and assessing which pipes might fail through inspections.

And, she said it’s more fair because it’s tied to how much any given property is contributing to runoff.

“We find that the stormwater utility fee is a much more equitable way to bill our customers,” Gurd said. “You could have a very large warehouse that has a lot of impervious surface and make[s] a big stormwater impact on all our infrastructure, but they may be a very low water user.”

In other places that don’t use a stormwater utility fee, money for this infrastructure is typically based on drinking water consumption.

That includes Cobb, where opposition to the stormwater utility proposal was swift and harsh. Residents poured into county commission meetings to protest, raising signs that said “No Rain Tax.”

One resident who opposed the measure is Tracy Stevenson.

“We are not against infrastructure and stormwater improvements — we realize they need to be done,” he said.

But, he takes issue with the county’s approach.

He thinks Cobb could allocate more money to stormwater from existing water system funds. He notes that right now, stormwater is just part of the overall water system in Cobb, and the rest of the system still raises more money annually. And some of that, he said, is transferred into the general fund each year. He said he and others wonder why more of that money can’t be used inside the Cobb water department instead.

“At the end of the day, what we want to see is an actual plan,” Stevenson said.

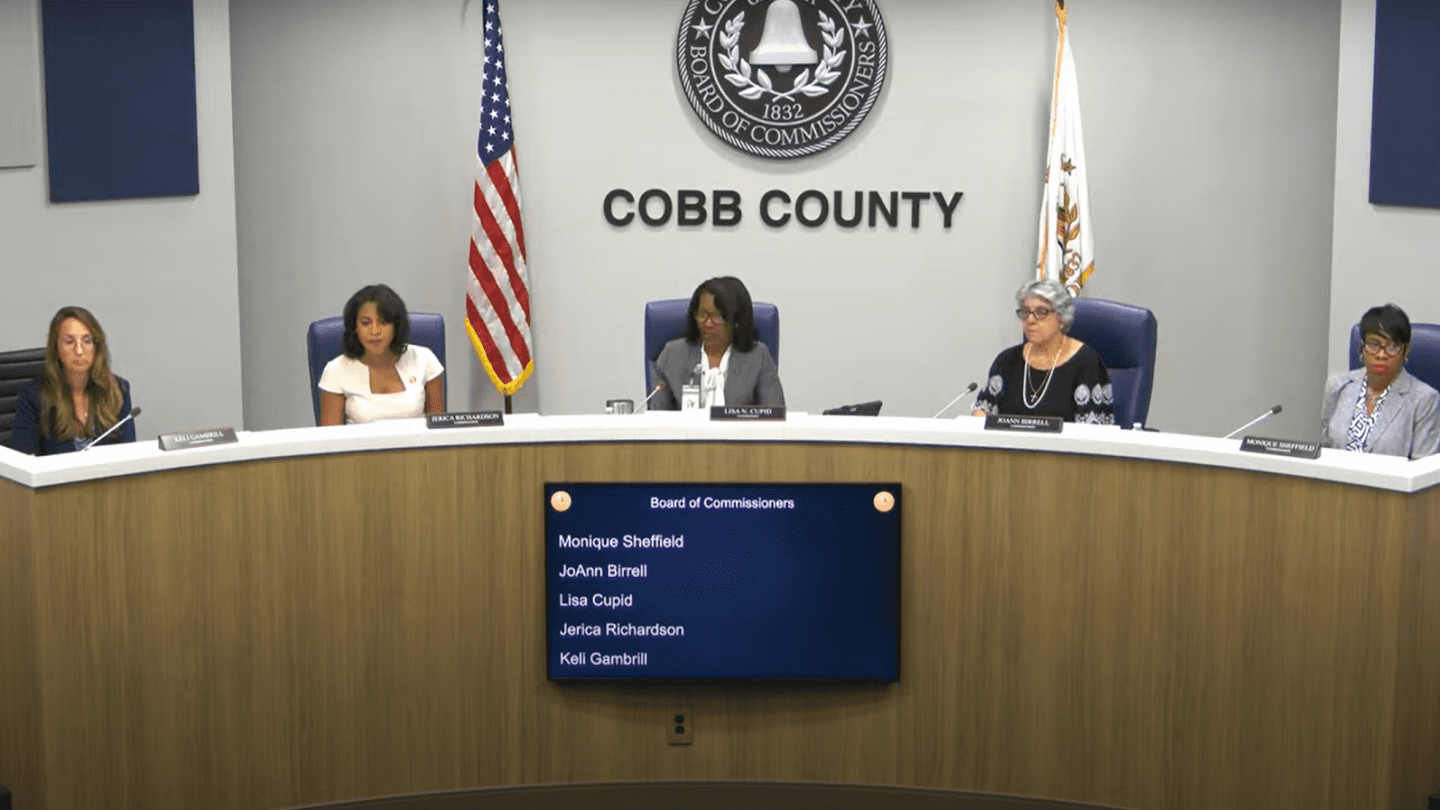

In early July, months of back and forth came to a close at the Cobb commissioners’ monthly meeting.

“Unfortunately, we just couldn’t come to a meeting of the minds,” said District 4 commissioner Monique Sheffield, addressing Jones with the water system. “But I just wanted to thank you publicly for all of the work that you put into this.”

The commissioners unanimously decided to indefinitely table the vote — meaning the proposal is dead.

Jones clarified if the idea ever resurfaces, they’d have to go through months of public notices, meetings and comments all over again. Multiple commissioners noted that this isn’t the first year that Cobb has tried to pass a policy like this one, and they said they recognized that stormwater was a problem that needed addressing in Cobb.

Chairwoman Lisa Cupid alluded to the fact that the commission may see Jones again when it’s time for them to draw up the annual budget, and that’s another way the Cobb water system could try to get more stormwater funding.

In a statement to WABE after the vote, Jones said the water system staff is back at the drawing board, and isn’t planning to propose this type of stormwater utility again.

Meanwhile, last month, a sudden downpour in a Cobb neighborhood clogged two large, 72-inch drainage pipes with debris and caused the front of the pipes to cave in, blocking rain water from flowing into the stormwater system.

Thirteen houses were flooded — five of which sustained major damage.

Cobb said in an email that emergency management and Cobb Fire worked with homeowners in four houses on the other side of the impacted drain pipes. With the prospect of more rain, and possible road closure for pipe repairs, those neighbors were told to move their cars out of their cul-de-sac.