Bat-Killing Fungus Spreads In Georgia

Black Diamond Tunnel sits just outside the city of Clayton in the northeast corner of Georgia.

In the mid-1800s, the tunnel was meant to be part of a train passageway connecting South Carolina to Ohio. After the breakout of the Civil War, construction stopped and never resumed.

Today, the man-made tunnel is the state’s largest known winter shelter for some of Georgia’s 16 bat species. It’s also the latest site in the state to fall victim to white-nose syndrome, a fungal disease that’s killed more than 6 million bats in the eastern half of the U.S. since it arrived from Europe in 2006. As heard on the radio

Almost immediately upon pushing off into the flooded tunnel in a small Jon boat, Katrina Morris, a bat specialist with the Georgia Department of Natural Resources, points to dead bats floating in the chilly, rippling water.

“Looks like a dead bat floating in the water, or maybe two. And that guy may not be alive. It’s hard to tell, but they get a lot of fungus growing on them,” Morris says, pointing to a more recent victim of the fungal disease. She keeps counting.

“I think that’s two dead bats,” Morris says. “When it was healthy there were over 5,000 bats in here, and this year during peak, we got 3,500.”

The tunnel is primarily home to tri-colored bats, one of eight bat species in Georgia affected by white-nose syndrome.

Deeper into the pitch-black tunnel, more bats dot the walls – more than a thousand. Below, a couple dozen dead bats float alongside the boat.

Near the tunnel’s end, Morris points out an infected bat, a male no bigger than a golf ball that’s just starting to wake up from hibernation. She pulls it off the wall to high-pitch shrieks.

“So you can see the angle and the fuzz growing up over his nose close to the eyes, on the ears, and on the forearm and the wing,” Morris says, describing the fungus that’s spreading over the bat. “It will grow on their feet and their tale. And it looks like they’re covered in a coating of white powder.”

Regina Bleckley, who owns the land on which the tunnel sits, says she knew something was wrong when a bat flew out in the middle of winter. She immediately called Morris.

“We came up here to clean it up, and here come a bat out, but it could barely go,” Bleckley says. “I knew right then. I went and called her. I knew right then they were sick.”

Bleckley was right.

As the bats hibernate, the fungus grows on their skin and fur. The fungus is itchy, so the bats wake up in the middle of winter when they’re supposed to be sleeping. Now awake, they leave the cave in search of food that doesn’t exist or fly around until they die.

“It meant something to this family,” says Bleckley. Her family ties to the land go back to 1919. She’s devastated the bats are dying on her watch.

“I guess that’s why it hurts. And I don’t know in my lifetime if they’re going to be able to wipe this virus out, the fungus. I’m worried about it. I’m scared about it,” Bleckley says.

Pete Pattavina of U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s Georgia office is also scared. He says the disease is so pervasive the agency expects to add another bat species, the northern long-eared bat, to the national endangered species list this fall.

Pattavina says it would be the first bat species added because of population declines caused by white-nose syndrome.

“I don’t think we really know what the trickle-down effect is going to be on our natural systems with whole species of bats not represented,” Pattavina says.

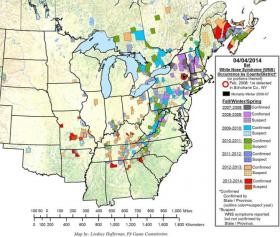

White-nose syndrome was first found in northwest Georgia early last year.

This year, the state Department of Natural Resources confirmed it had spread farther south and to the northeast corner of the state, including Black Diamond Tunnel.

The fungus, which is primarily spread from bat to bat, has been confirmed at 12 sites in Georgia so far. Currently scientists have no way of stopping it from spreading to more.

“You’re talking about miles and miles of cave with bats that are 100 feet up in the ceiling. Treatment will be nearly impossible even if we do find a compound,” Pattavina says.

That’s not to mention the spots researches can’t get into, should a treatment be found.

In Georgia alone, there are 600 caves, tunnels and mines that could be home to bats. Only 20 are accessible to the state.

Chris Cornelison, a postdoctoral researcher at Georgia State University studying white-nose syndrome, says despite those odds, scientists have to try to find a cure.

“Right now we’re seeing up to 100 percent mortality,” Cornelison says. “And so if we continue to allow this to go, there’s nothing that would indicate that we won’t be in a world without bats – or at least a North America without bats – at some point.”

Cornelison thinks he’s found a type of bacteria that stops the growth of the fungus. He’s seen positive results in the lab so far.

Cornelison says his experiment is one of two in the U.S. ready to go to trial with live, wild bats, and he’s been in talks with Tennessee officials about introducing the bacterium at a retrofitted military bunker this fall.

There’s more good news.

Researchers say if a bat can survive the winter, it can clean off the fungus and live. Because the South’s winters are shorter and milder, there’s hope the region won’t see the population declines that some states in the North are experiencing.

Some bats have also resisted the disease, and Cornelison says scientists are trying to figure out why.

Cornelison says the research is necessary because bats are vital to the country and the state’s agriculture industry.

Scientists estimate a single bat can eat up to its entire body weight in insects in one night.

The U.S. Geological Survey says bats save the country’s agriculture industry between $4 and $50 billion a year in pest control services. That’s not all.

“There’s an entire other dynamic that has not gotten the same amount of attention as that, and that is their behavior as pollinators,” Cornelison says. “And these bats tend to serve as exclusive pollinators to some plants.”

For now, scientists can only track the disease as it spreads through more of the country, killing more bats in its wake.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))