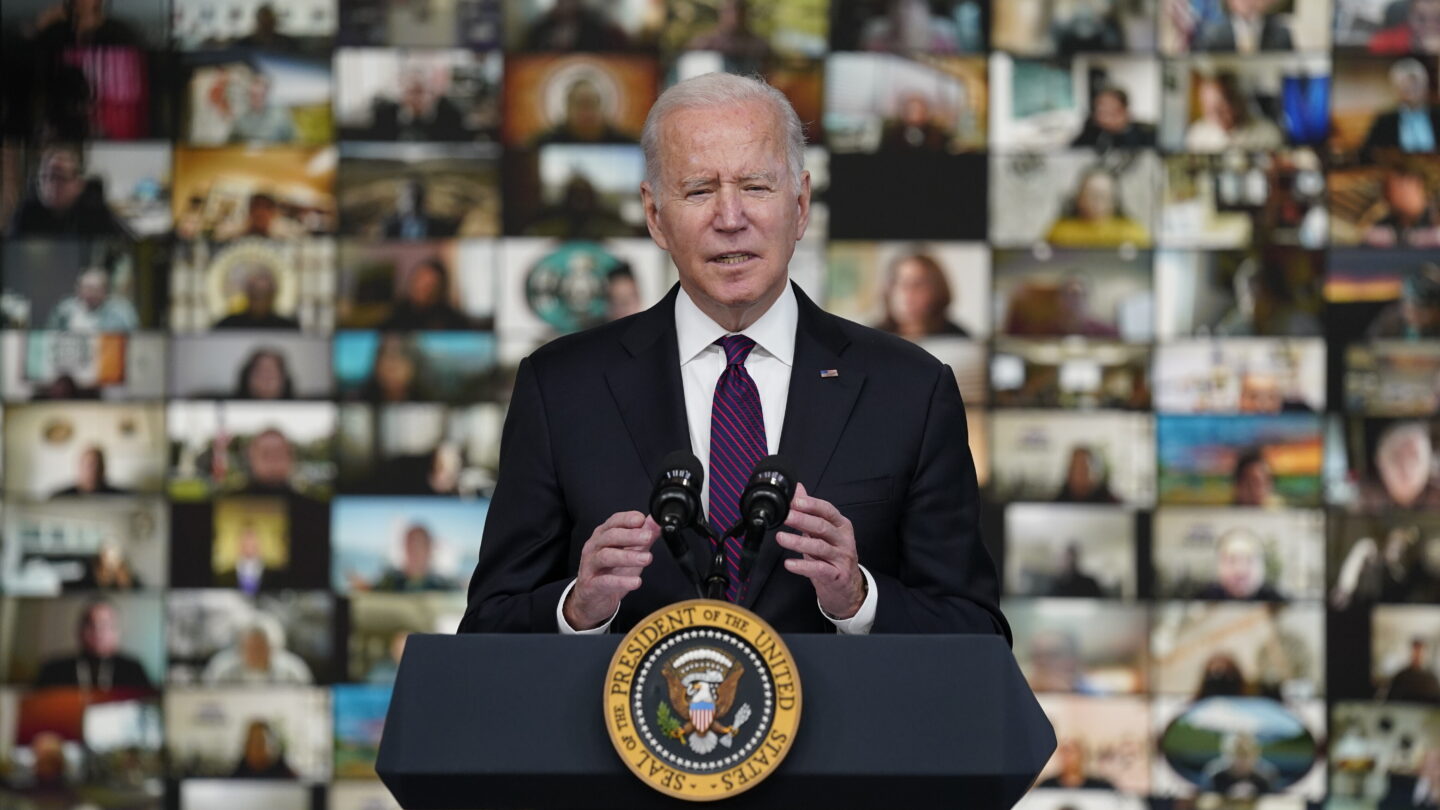

President Joe Biden plans to make new commitments to Native American nations during the government’s first in-person summit on tribal affairs in six years.

The changes include uniform standards for federal agencies to consult with tribes, a plan to revitalize Native languages and new efforts to strengthen the tribal rights that are outlined in existing treaties with the U.S. government. Biden, a Democrat, is scheduled to address the White House Tribal Nations Summit on Wednesday, the opening day of the two-day summit.

The gathering coincides with National Native American Heritage Month, which is celebrated in November. Leaders and representatives from hundreds of Native American tribes are expected to attend.

The Biden administration said its goal is to build on previous progress and create opportunities for lasting change in Indian Country. However, the lasting nature of Biden’s commitments isn’t guaranteed without codified laws and regulations.

“It changes with each president,” said Jonathan Nez, the leader of the Navajo Nation in the U.S. Southwest. “And even if it’s legislated, it takes a significant effort especially when, at times, tribal issues take the back seat to larger, national issues.”

Federal agencies recently have been creating tribal advisory councils and reimagining consultation policies that go beyond a “check the box” exercise. Some of the more significant changes involve incorporating Indigenous knowledge and practices into decision-making and federal research.

Nez has been advocating for a speedier process to get infrastructure projects, including internet access, on the Navajo Nation, which stretches 27,000 square miles (70,000 square kilometers) into New Mexico, Arizona and Utah. He said it requires constant advocacy.

“You’ve got some new congressional officials who just got elected also, so there’s going to be more educating that has to be done,” he said.

The Biden administration also planned to announce Wednesday that the Commerce Department will work with tribes to co-manage public resources like water and fisheries. The Agriculture Department and the Interior Department have signed 20 co-stewardship agreements with tribes, and another 60 are under review, the administration said.

A new report being released in conjunction with the summit will outline best practices on integrating tribal treaty rights, like hunting and fishing on ancestral lands, into the decision-making process for federal agencies.

The tribal nations summit wasn’t held during then-President Donald Trump’s administration. The Biden administration held one virtually last year as the coronavirus pandemic ravaged the U.S. and highlighted deepening and long-standing inequities in tribal communities.

Both administrations signed off on legislation that infused much-needed funding into Indian Country to help address health care, lost revenue, housing, internet access and other needs. The 574 federally recognized tribes in the U.S. received a combined $20 billion in American Rescue Plan Act funding under the Biden administration.

Trump, a Republican, signed the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security Act, which provided $8 billion to tribes and Alaska Native corporations but had more rigid guidelines on how it could be spent. The Treasury Department was sued over how that funding was allocated and faced harsh criticism for the time it took to get the money to tribes.

Biden’s Treasury Department said it prioritized tribal engagement and feedback in distributing funding from the latest aid package. A report being released Wednesday by the administration outlines how tribes spent the money on more than 3,000 projects and services.

The Karuk Tribe in northwestern California, for example, used some of the aid for permanent and temporary housing after a wildfire that burned 200 homes in the Klamath Mountains displaced tribal members.

The Native Village of Deering and other tribal governments in Alaska pooled funds to ensure access to preschool and free meals, along with extra servings in an area where food has been scarce.

Other tribal communities across the U.S. have spent the money on housing for tribal members, transportation to veterans hospitals, after-school facilities, language and culture programs, emergency services and health care facilities.