New Georgia political maps have been signed into law by the governor after Republican state lawmakers unilaterally passed revised district lines ahead of a court-imposed deadline on Friday.

But even with the close of the special legislative session on Thursday, uncertainty remains over the fate of Georgia’s maps for Congress and the state legislature.

The new maps will now be subject to court review, appeals could drag on for months and meanwhile, incumbents and potential candidates for office are up against a March qualifying deadline to decide where to run.

Lawmakers were forced to redraw the maps approved during the 2021 redistricting cycle after a federal judge found that they violated the Voting Rights Act by illegally diluting the power of Black voters.

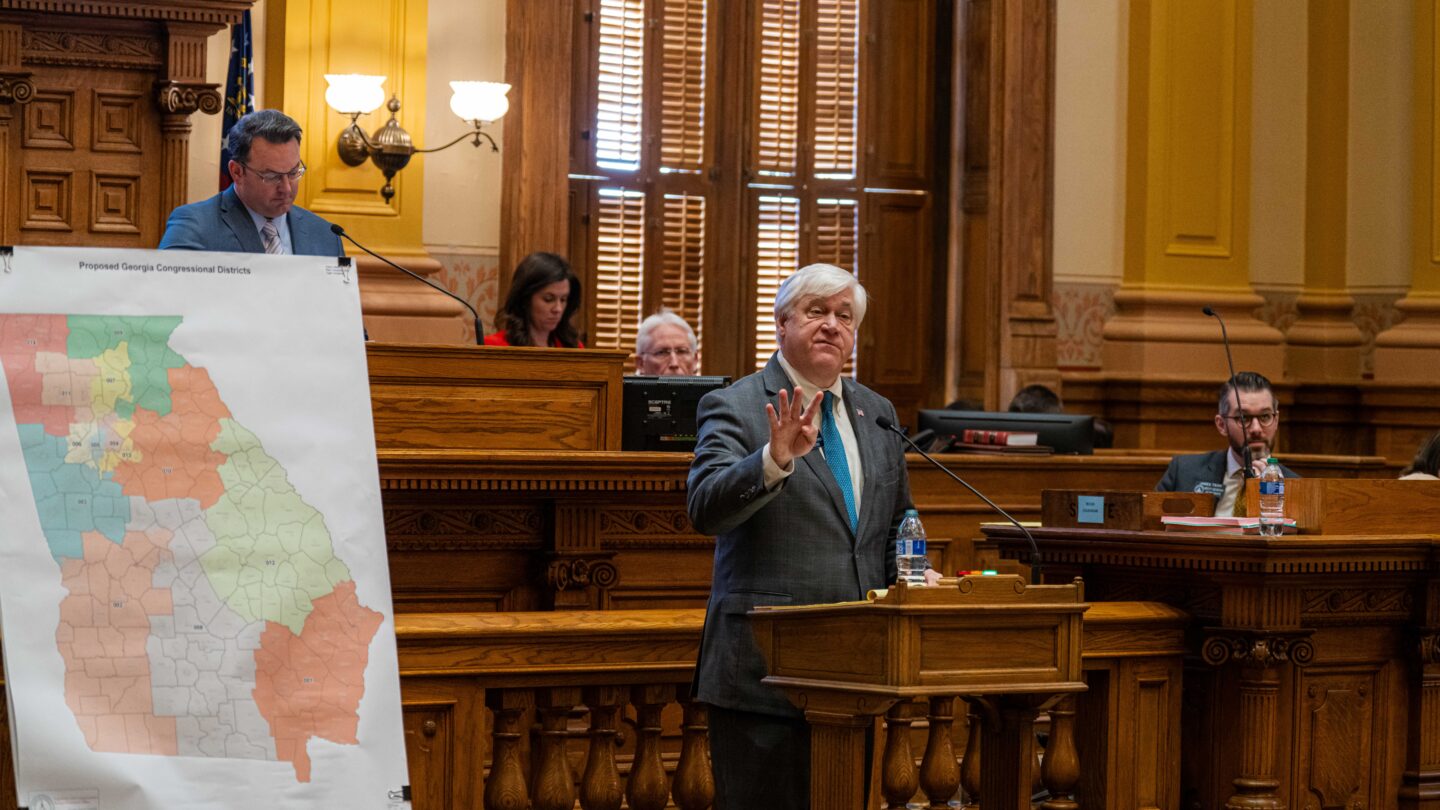

The Republican majority proposed and approved a Congressional map that creates a new, majority-Black district on the west side of Metro Atlanta. The map will likely keep the GOP’s 9-5 political advantage intact.

The approved state House map creates five new, majority-Black districts in Metro Atlanta and around Macon, but pairs mostly Democratic incumbents to limit the minority’s gains to roughly two seats.

The new state Senate map creates two new majority-Black districts, but is drawn to keep the balance of power in the chamber unchanged.

Here’s what happens next:

Judge to review new maps

U.S. District Judge Steve Jones, who ordered Georgia lawmakers redraw the maps, will now review the maps passed by the legislature.

The courts have the final say over whether the new maps adhere to the order. Jones has set a hearing for Dec. 20.

Republican lawmakers, who drew the maps, say they followed the order’s directions — creating the specified number of new majority, Black districts.

But Democrats say the maps do not comply with the judge’s instructions by failing to address certain districts identified as diluting the power of Black voters. They also say the new maps defy the judge by dismantling districts that are majority-minority, but not majority-Black.

“We are reviewing the state legislative maps that were passed and are disappointed that the General Assembly chose to not fully comply with Judge Jones’ order,” said the ACLU of Georgia, which is representing one of the plaintiffs who filed a lawsuit against the original maps. “We plan to address this non-compliance in court.”

Jones is expected to hold a hearing soon to weigh whether the maps comply with his order. If he decides they do not, he can appoint a special master to draw maps, independent from lawmakers.

Next door in Alabama, a court-appointed special master ultimately drew the maps after the courts found the revised maps passed by the legislature still did not comply with the Voting Rights Act.

Legal challenges likely to continue

Even as lawmakers advanced the new maps, the state was simultaneously working to appeal the judge’s order to draw new maps at all.

Republicans continue to assert the existing maps they passed in 2021 comply with the law.

If an appeals court agrees with them, the redistricting legislation passed this week would revert Georgia back to the old maps.

Separately, if the judge finds that the new maps passed this week still do not comply with his order, the state could appeal that decision, too.

A key question that case would likely raise is whether majority-minority “coalition” districts are protected by the Voting Rights Act.

The new maps eliminate several existing majority-minority districts, including the 7th Congressional District, which is home to significant populations of Black, Hispanic and Asian American voters and is represented by Democrat Rep. Lucy McBath.

In his ruling, Jones warned Georgia lawmakers not to create new majority-Black districts at the expense of “minority opportunity” districts.

But the federal appeals courts have not reached a consensus on whether the VRA protects these districts. The U.S. Supreme Court has yet to weigh in on the question, meaning Georgia’s new maps could end up in front of the high court.

Judges have historically been hesitant to order changes to voting procedures as elections approach. That means one set of maps may end up locked in for 2024, even if they are ultimately tossed by the courts for the next cycle.

Qualifying deadline ahead

While legal challenges may continue well into next year, candidates for office have to register to run in 2024 by March 8.

While candidates for Congress do not have to live in the district they run in, candidates for the state House and Senate do. Plus, several state legislative districts in the new maps pair incumbents against each other, meaning there could be potential reshuffling afoot.

That means potential candidates and incumbents in districts under scrutiny by the courts are having to make decisions about their campaigns knowing the maps may still be in flux.