Auburn Avenue was once the epicenter of successful Black enterprise in Atlanta, if not the country. Veteran business owners and a new generation of entrepreneurs are determined to navigate obstacles and continue that legacy.

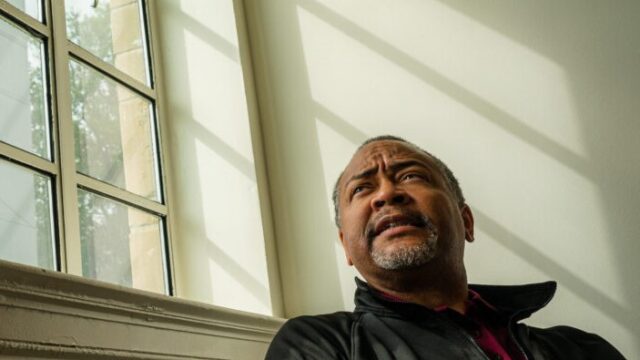

Devon Woodson is a fourth-generation owner of Pal’s Lounge, a historic blues hot spot that has remained a pillar of Sweet Auburn’s artistic showcase and community fellowship.

Established by his great-grandfather Robert Lee Murray, a neighborhood community leader, the lounge has been serving the Sweet Auburn community for over 50 years. The site was originally built in 1890 as The European Hotel, Atlanta’s first Black-owned hotel.

As a child visiting his grandmother at the club, Woodson fondly recalls hearing all of the music, laughter and heel-tapping that nestled throughout the lounge’s walls any given night. The experience lives on with Woodson’s five-year-old daughter, who often accompanies her father to work.

The venue still holds an open door for local acts and a feeling of family for longtime patrons and newcomers, something that Woodson hopes to continue for years after him.

“Having a generational business takes away from things just being about you,” said Woodson. “It’s like a living organism that changes over time, something that you see as having to live beyond you. Something that was here before you and something that should be here after you, that to me is my daily responsibility. To me, there is no not surviving.”

The lounge proprietor, who also serves as president of the Fourth and Sweet Auburn Neighborhood District, is one of the few remaining examples of generational wealth that has continued to flourish throughout the businesses in the district.

“Part of the legacy is based on business and ownership,” he said. “The main reason why we as a community have a problem growing is the level of ownership that we have. We rent, we lease, but we don’t own. It’s because my family has owned the property that they have put me in a position of leadership of what I can do with my space. I have more of an insight of what’s going on.”

Across the street from Pals, Sweet Auburn Bread Company owner Sonya Jones is storing away her products after a day of baking and welcoming back familiar customers.

A 25-year veteran of Sweet Auburn, Jones opened the bakery specializing in southern deserts in 1997. Then-President Bill Clinton visited during her freshman year of business.

“I feel that it is a great place, especially for a Black-owned business in the city of Atlanta to be,” she said. “I love the history of it, and I feel like it still resonates. I think you will find that the businesses that have been staying here, there is a connection to the significance of Auburn Avenue.”

And while she’s still proud to be a part of the community, Jones noted substantial changes from when she first opened up her doors.

“It has been crazy, the development [downtown], but the development has been very slow on Auburn Avenue,” she said. “It’s all around us, right at us … but still not close enough to really affect us.”

Since opening her doors, Jones says that changes within the community, such as the dissolution of residential areas, construction of city infrastructure projects such as the Atlanta Streetcar and a lack of parking, have led to obstacles in attracting customers.

“Thankfully, we have some lighting on Auburn now, but it took nearly an act of Congress to get it,” said Kimberly Alexander, operations manager of the Odd Fellows Building, where Sweet Auburn Bread Company is located. “We are now in a situation where parking has become untenable.”

While the businesses on Auburn Avenue still struggle with promotion and stable clientele, a resurgence in popularity has emerged on the neighboring street, Edgewood Avenue, also a part of the Sweet Auburn District.

“Before, there were more people actually living down here. Now, the college kids are here, where they are more of a transient community — here for three or four years, and then they are gone,” said Woodson.

Though undergoing significant gentrification in recent years, Edgewood is one of Atlanta’s go-to hotspots for dining, nightclubs and entertainment, particularly for Black-owned businesses.

“If you look at Edgewood, it’s a different kind of street. There are restaurants and clubs. It’s an entertainment district — it’s going to be appealing. There’s a succession of opportunities for people to go place to place, to hang out. And Auburn is not built that way,” said Jones. “You may think logically that [clientele] would trickle over here, but I haven’t really seen that.”

Georgia State University has been crucial in new developments throughout Sweet Auburn in recent years. The public university has bought and refurbished properties throughout the area, including the Citizens Trust Bank Building and Citi Auditorium.

And although Georgia State has its logos throughout the community, longtime business owners say the school hasn’t reached out for their input.

“They’ve never come to have a conversation with us other than they want to know if they want to sell our building,” said Alexander.

Woodson, however, sees the inclusion of Georgia State and other new business ventures in the community as a way to breathe economic growth back into Sweet Auburn.

“I think one of the main things about the past and the future will be that a lot more big money that will be here,” said Woodson. “There are other corporations coming, hotels building, new money coming in. Before, it was more about families and people who owned the properties. Now, it’s less that and more about ‘what’s the new community going to look like.'”

“I feel that it is a great place, especially for a Black-owned business … I think you will find that the businesses that have been staying here, there is a connection to the significance of Auburn Avenue.”

Sonya Jones, Owner – Sweet Auburn Bread Company

One of the newest editions to the avenue has been the Peach Cobbler Factory, a popular dessert shop that celebrates its one-year anniversary in May.

A family-run location, franchise owners Peyton Williams and Dorian Allen were enthusiastic about the opportunity of bringing their first joint business venue onto the avenue.

“I think that it’s empowering to know that you have so much greatness on the street, and I definitely want to be a part of bringing it back to what it’s supposed to be,” she said. “I think that it can be so much more than what we limit it to sometimes.”

While being located at the corner of the street has made her store more accessible to Georgia State students and tourists walking across the city, she had been surprised at the demographic that primarily visits the shop to patronize and ask questions about the neighborhood’s history.

“Typically, the main ones who come in and support … who are intrigued about the history are people who don’t look like us,” said Williams. “People who work in civil rights and who advocate for it, who honestly don’t look like us. I also do have a lot of older Black people who come in and share the history with me.”

Hoping to continue with the legacy the area has for building up young leaders, half of the Peach Cobbler Factory’s staff is made up of local Georgia State students and high school students, many embarking on their first job.

When asked what she sees for her location in the future, Williams only hopes that she will influence other budding entrepreneurs in the same fashion that Black business leaders such as Alonzo Herndon and Robert Lee Murray have done for her.

“I really want it to be a staple. I want it to be a space that is also influential … where people are able to utilize it to create greater things. I want to continue to use it to give back and bring more knowledge about our culture and who we are,” she said as she looks outside the restaurant’s window at college students walking past the street. “It’s important that we, as Black Americans know that this is our culture.”