If you read L. Frank Baum’s 1900 book, “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz,” there is Dorothy, a Cowardly Lion, a Scarecrow, a Tin Man, Toto and a pair of silver slippers.

Hollywood took some artistic liberty with that detail in the 1939 film “The Wizard of Oz,” where Dorothy, of course, wears ruby slippers.

The change to shoes that popped was made because the studios were using the reigning color technology of the time: Technicolor.

Color had always baffled the Hollywood studios. There had been experiments, like tinting or dying sections of film to reflect a certain mood, but the studios were not about to come up with color film themselves.

“The studios are ‘dream factories,’” explained Georgia State and Emory University film professor Harper Cossar. “They make stories…They aren’t technology firms.”

Technicolor founder Herbert Kalmus was a scientist and engineer. He incorporated his company in 1915, even though he and his team were years away from the first three-color process feature film, “Becky Sharp,” which was released in 1935.

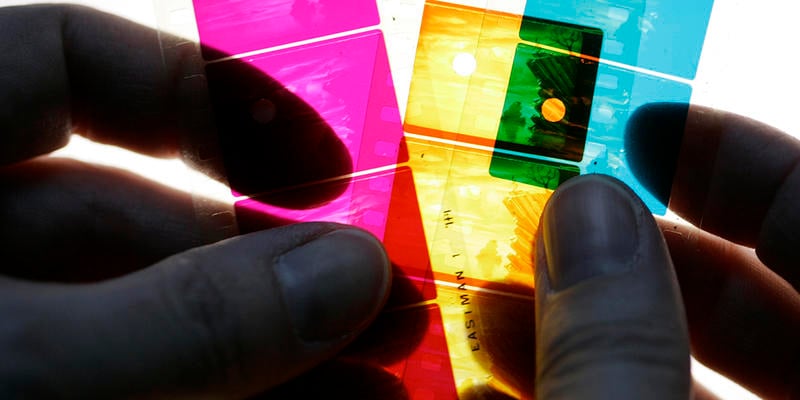

The Technicolor engineers did not invent film stock that could actually capture color. Instead, they developed a camera with a prism beam splitter that filtered lights onto black and white film strips — one for green, one for blue and one for red. Once shooting wrapped, the film strips were dyed the appropriate color and then layered on top of each other to create “glorious Technicolor,” as it was called.

“Glorious” it may have been, but it was also inefficient and posed massive problems for Hollywood. The industry needed to operate at maximum efficiency to produce hundreds of films per year per studio.

“Technicolor is almost the far reaches of inefficiency,” said Cossar. “You have to get a Technicolor producer, you have to rent a Technicolor camera, you have to hire Technicolor cameramen, you have to use makeup to accommodate the extraordinary lights and you have to have the film processed and printed in a Technicolor lab.”

With the introduction of Technicolor, what Hollywood had previously done in-house, they now had to farm out to Technicolor. The process was also three times as expensive because studios had to use three times the amount of film.

The new makeup looked like pancake batter. The “extraordinary lights” that Technicolor technology required were so “extraordinary” that some actors said they had permanent eye damage from working on set.

These innovations were required to make colors pop. If a shade was too subtle, it might not end up as the right color — hence why Dorothy wears ruby slippers instead of silver.

Film producers and directors questioned the necessity of Technicolor staff on set, particularly considering the case of Natalie Kalmus, founder Herbert Kalmus’ ex-wife. They divorced in 1921, though they lived together into the 1940s.

Cossar explained, “As part of the divorce degree from 1933 to 1956, Miss Kalmus has 346 credits in film, and she’s normally listed alongside the cinematographer as the ‘Technicolor Color Consultant.’”

Hollywood had to hire a whole team of Technicolor experts to use the technology, but Natalie Kalmus was not an expert.

“The idea that you have someone who, as the result of a divorce decree who is sitting on the set who doesn’t have much of a cinematic background, telling production designers and costume makers, cinematographers, gaffers, lighting technicians about how things should proceed, what to do about how things should proceed,” said Cossar, “I think anyone could imagine that is an interesting production to be involved with.”

In retrospect, some people describe Technicolor as “garish,” “weird” and “unrealistic.” The phrase “in glorious technicolor” is often used pejoratively, meaning too brightly colored.

Indeed, the colors are bright, deep and lush.

“It did have this kind of fantasy color to it and it really did have this bubblegum candy look to it,” said Cossar. “Yeah, it was real but it was not real but it was fantastic and gorgeous to look at.”

Some of Technicolor’s crowning achievements included “The Wizard of Oz,” “Singin’ in the Rain” and “Gone with the Wind.”

During its era, audience members did not criticize Technicolor’s quality. It was the only color standard seen by wide audiences.

“Let’s not forget the historical context of when we are making these Technnicolor films in the 30s and 40s,” Cossar said. “It was either the Depression or we’re looking at Europe, the coming of World War II. And, a little fantasy and a little escape that looks like a dream, that’s not a bad thing to be selling.”

Technicolor is still a technology company, but it was cast aside as the Hollywood standard in the 1950s when Eastmancolor developed a more efficient and less expensive film stock and process.

Even with its inefficiencies, though,Technicolor still reigned for over three decades as the technology that made the Golden Age of Hollywood really shine.