The city of Brunswick has escalated its fight against a Christian homeless day shelter working in the historic downtown by filing a federal lawsuit that seeks to shut it down.

The lawsuit alleges that The Well, which uses private donations to serve individuals facing homelessness, is a public nuisance and should no longer be allowed to operate. But the ministry says the lawsuit conflicts with a larger issue about the separation of church and state.

The shelter, the only one of its kind in the city, does not violate any zoning or municipal laws. Yet Brunwick officials have taken the side of residents and business owners in the wealthy downtown area who are worried that the homeless population pose a public safety threat, a perception that crime statistics suggest is overstated or incorrect.

A federal judge has yet to schedule a hearing on the suit against Southeastern Educational Services, Inc. the church that operates the shelter, for an injunction to close its operations for good. In the meantime Brunswick Police Chief Kevin Jones appeared to undermine one of the main arguments raised by the city in its filing.

Jones told The Current that no crime has occurred at or near The Well since April, when it closed voluntarily in reaction to official pressure. After the shelter reopened last month with enhanced protocols for residents, police have responded to five calls, including a welfare check, an attempted suicide and an officer-initiated checkup.

The way they’re operating things now is a lot more efficient and puts less strain on the police department,” Jones told The Current.

The Well, in responding to the city suit, argues that the city has no legal basis to shutter its work. The religious organization emphasized that as recently as 2022 the municipality had praised the quality of its services in a mandatory federal report, noting that the religious organization helps the city address emergency shelter and transitional housing needs.

“While The City may argue that public safety is a compelling governmental interest, that concept here is at least debatable given The City’s failure to police its own streets,” the document reads. “The more compelling government interest is The City’s utter failure to address the plight of the homeless in its environs.”

The city did not respond to requests for comment.

The federal case is the latest twist in a political battle between the religious leaders who support The Well, and city officials who have fought to close the shelter in its current downtown location while also rejecting alternative measures to minister to the estimated 100 people who use its services.

The issue boiled over in April when city officials waged a pressure campaign to close The Well, despite having no evidence of legal violations. Staff members agreed to close temporarily to strengthen security protocols at the shelter.

Dozens of people were left with no place to go when it closed.

Shortly after The Well softly reopened its doors in July, the city filed suit in county court, calling it a public nuisance and asking for a temporary restraining order to shut it down immediately, public records show.

The case was elevated to federal court in August because The Well lawyers argued against the injunction by citing First Amendment constitutional protections. The shelter’s lawyers also cited a law that forbids state governments from imposing regulations that substantially burden religious institutions.

Confusing crime statistics

One of the documents the city has submitted to support its suit is data that supposedly shows approximately 2,300 emergency and police calls involving The Well between January 2018 and April 2023.

However, a data analysis by The Current found errors in the data. At least 370 of these calls were listed twice.

Meanwhile, approximately 25% of the roughly 2,000 unique calls came from officer-initiated activity, rather than the community complaints, according to the data analysis.

The chief said that while The Well had more calls for service than any other property in Brunswick during this period of time, the calls have been largely nonviolent and alone do not suggest a larger preponderance of crime.

According to the city filing, 40 calls were made in response to an alleged assault, and fewer than 10 calls for harassment or drugs.

The other most common entries include calls for a problem person, which is most often when someone is drunk, arguing or causing a disturbance, and suspicious person and follow up calls.

Only about a third of calls lead to officers writing an incident report, Jones said.

The city attorney did not respond to requests for comment.

Community weighs in

The lawsuit also included an email from the executive director of the Downtown Development Authority asking residents to give feedback about The Well. The filing includes nearly 50 responses from residents and business owners with strongly worded negative opinions about the shelter.

Many respondents demanded that The Well remain closed.

- “The homeless and mentally ill population became out of control when The Well was operating, bringing violent crime and blight to downtown,” said Liane Brock, a resident of nearly 30 years. “Homelessness is a National problem that needs to be solved, but it is not fair to put us in harm’s way to solve it. There are other ways.”

- “Almost immediately after The Well closed its doors, the entire downtown area became far more pleasant and less threatening,” President of Torras Properties Darren Pietsch said. “Every other person I have talked to that works in the area feels the same.”

- “The Well closing was the best thing for my business, and me and my family’s general safety,” Danielle Sunderhaus with the Market on Newcastle wrote. “My customers at The Market started returning and revenue increased once the Well closed.”

An email response made on behalf of the entire board of directors of the Safe Harbor Center, an organization that provides services for at-risk families, children and individuals, said the two months when The Well was closed was a “wonderful respite.”

“‘The Well’s’ mission of helping the homeless is one we can all agree with,” Safe Harbor Center’s email states. “It is their execution of that mission that puts our children, and our community, at risk. Adequate supervision and programming are not present.”

One email suggests there will be political consequences for city officials who fail to close The Well.

“You are public servants paid to protect citizens,” an email sent from Coastal Therapeutic Massage states. “Downtown people are talking and there will definitely be a shake up next election if something isn’t done to prevent this,” it continued.

Some residents offered potential solutions that often involve moving The Well out of downtown, but not shutting it down completely.

“We still have a long way to go to address the homeless population,” Susan Bates wrote on behalf of Tipsy McSway’s Neighborhood Bar & Grill. “Maybe there could be the creation of a safe place, out of the public eye, for restrooms and shade that The Well could provide?”

The emails were written in June, before The Well reopened and changed their safety procedures. So far, the federal court filing has no complaints made during the last month since the shelter has restarted operations.

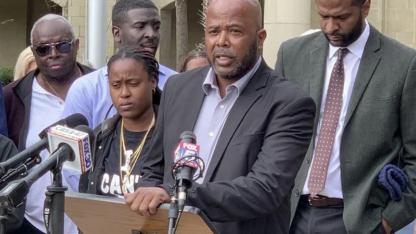

The Glynn County Clergy for Equity held a press conference Aug. 9 to show its support for the staff of The Well. In light of The Well’s recent changes, the group urged the city to give The Well a trial period through the end of the year before taking legal action to oppose it.

“We don’t have a homelessness problem,” Rabbi Rachael Bregman said. “We have a compassion problem.”

The Well’s response

The Well has made significant changes since it closed in April, according to Jenna Kennedy, the FaithWorks Minister of Operations at The Well, including cracking down on loitering.

The approximately two dozen homeless people who used to sleep on its porch, as well as people who hung out at a wall across the street from The Well, are no longer present on the property, according to Kennedy.

The ministry installed cameras that send alerts to a staff member’s phone so they can call the police if necessary – though that has not yet been necessary – and a fence for the front porch has been ordered.

But so far, people have listened to staff when they ask them to stop loitering, Kennedy said. “It hasn’t been an issue.”

Chief Jones agreed.

Calls about the homeless population increased from June to July, he said, but they were mainly concentrated in areas away from The Well, according to a report he shared with The Current.

Kennedy says that downtown business owners have superficial perceptions about her ministry without ever looking inside.

“Our biggest issues have been what people see on the outside and think about what’s happening on the inside,” Kennedy said. “Once you get inside, it’s always the same environment.”

When The Current spent the day at The Well on Aug. 3, clients were quiet, resting, reading or making phone calls to family on an assortment of mismatched chairs and tables while staff washed their clothes and prepared food donated by community members.

It’s a significant improvement from what conditions used to be like at the day shelter, according to Ralph Carpenter who works at the kitchen and has used services at The Well since it opened in 2015.

One of the new protocols is that homeless people must submit to an in-depth registration and get cleared by the police that they have no outstanding warrants before receiving help at the shelter.

Additionally, a new sign-in system that will flag anyone who is not allowed in the building. Guests are required to meet with the resource management team after every 14 visits to The Well to create a plan forward and work on getting identifying documents if they’ve lost them.

Staff are required to obtain mandatory mental health and de-escalation training Kennedy said.

The changes have made The Well a safer place, Kennedy said, whether her neighbors acknowledge it or not.

“What’s hurt the most to me, as an individual, is just realizing the lack of compassion people have for human beings,” Kennedy said. “I think the city and other people think that if they just make the environment in the city so inhospitable, (homeless) people will move on. But that’s not the case.”