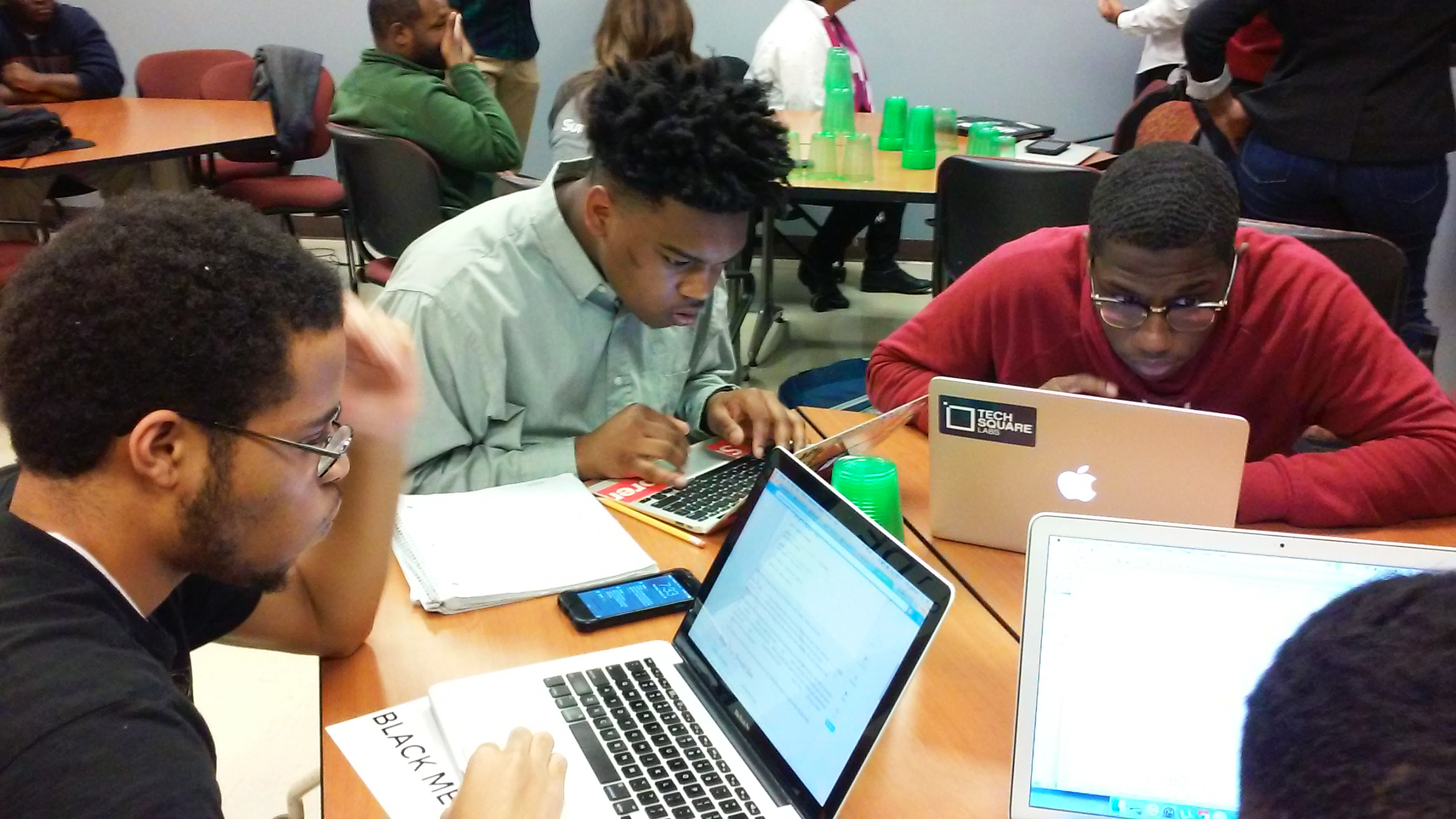

At Tech Square Labs in midtown Atlanta, you’ll find glass walls and high ceilings. It follows the typical design trends of today’s “hip” innovation centers and co-working office spaces. It’s also where 14 low-income African-American students are learning Java as part of the Code Start program.

Code Start is a free, year-long training program for low-income people between the ages of 18 and 24. Participants must have a high school diploma or GED, but not a college degree. Rodney Sampson started the program. He calls Code Start, “an experiment on whether or not we can take ‘disconnected youth,’ who’ve been labeled by the system, and teach them how to be a junior level software engineer or developer.”

The idea for Code Start was born last summer, when the director of Atlanta’s Workforce Development Agency, toured one of Sampson’s minority coding and entrepreneurship classes. Katiana Stevens, says the program is intense, but having classmates she can relate to, helps. “A lot of us have been on the verge of tears after the first week,” Stevens says. “However we’ve built a strong sense of community, really fast. So we’ve all muscled through, we support each other and tell each other to keep going.”

Sampson is all about diversifying the tech industry by empowering African-Americans to start their own companies. That’s why the program also focuses on career readiness and teaching students how to be entrepreneurs. Georgia Tech assistant business professor Seletha Butler says mentors like Sampson are crucial to African-Americans who want to make their way in the tech industry. “From the hiring process, if you have that mentor, you have someone to sort of prep you in terms of things that you should be doing in the interview,” she says.

And helping candidates overcome cultural differences is still crucial, even for African-Americans who have strong academic credentials. During a recent class at Morehouse College, Michael Street was teaching freshmen how to code in a language called Python.

Street isn’t waiting around for tech companies to change their approach to recruiting diverse talent. Through his group Black Men Code, Street preaches the gospel of STEM at his alma mater. But even at historic Morehouse, famous for graduates like Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Spike Lee, there’s an understanding that the color of your skin can limit access to capital, resources and opportunities in the overwhelmingly white tech sector.

“So you have an institution that’s largely homogenous and you may have the skills to get in there, but they’re going to say you’re a bad cultural fit,” Street says. “It’s really, I mean, a massive challenge because these companies have been making billions and billions of dollars operating in the way that they’ve operated.”

And Street knows it’s not just inside the tech industry where his students will face challenges. “There’s still so much latent cultural bias in day-to-day interactions, which we see playing out in police officers and black males.”

That sort of bias hit close to home recently for Code Start founder Rodney Sampson, and he recalls how it how it has already affected his students. “I was actually in a meeting – a very important meeting,” he begins. “And I get a call from my resident director and says you need to leave your meeting now and you need to come down to the Atlanta Check Cashing outlet on Forsyth Street.”

One of his Code Start students had tried to cash his monthly $500 stipend, but the clerk suspected the postal money order was fake. She took his identification and told him to call the police on himself.

When Sampson arrived, the 19-year-old was in handcuffs in the back of a police car. And when Sampson spoke up for his student, officers immediately began to grill him about the money order. “And so they were like, ‘Do you have the receipt?’ At first I was like, I don’t have to prove that I purchased something. But here I am pulling out a receipt on Forsyth Street in downtown Atlanta, showing these officers that I purchased all of these money orders, so I was a little uncomfortable doing that.”

After 30 minutes of back and forth, the student was released from police custody. He got his money order and ID back, but the incident shook him so much that he dropped out of the program.

Still, Sampson says he’s not giving up on this student or his mission to help the other young people transform their lives. “What we’re realizing is that they’re not just hacking the tech industry,” Sampson says. “They’re learning to hack themselves and changing the perspectives of how other people see them.”

Sampson is going to be teaching those lessons – including resume writing, interviewing skills and cleaning up social media profiles – as Code Start continues this summer.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))