Each week, we answer “frequently asked questions” about life during the coronavirus crisis. If you have a question you’d like us to consider for a future post, email us at goatsandsoda@npr.org with the subject line: “Weekly Coronavirus Questions.”

The best laid plans of coronavirus caregivers can go kaflooey.

When Marie Loveheim was recovering from COVID-19, alone in her apartment in Washington, D.C., she didn’t have a thermometer. So her son bought her one.

It registered a fever of 107.

“Was I dead?” she wondered.

Thermometer number two came from her daughter, who ordered it as part of a grocery delivery from a supermarket.

But what came was a meat thermometer. Lovenheim’s sister suggested she check to see if she measured “medium-rare.”

When a loved one gets sick, our gut response kicks in like second nature: Provide as much care and comfort as possible. Send a thermometer, a soup, you pick: It feels like a no-brainer.

But how do you care for a loved one struck by a fast-spreading virus that means it’s high risk to have face-to-face contact with a patient lest you get sick yourself?

NPR spoke to medical professionals and COVID-19 recoverees about the trial and error of caregiving: What works, what doesn’t and what might provide hope and humor even at the unlikeliest of moments.

To begin, there are the practical considerations.

Dr. Paul Sax, clinical director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, says if a loved one has COVID-19, the first step is home isolation. If possible, the infected family member should remain quarantined in a separate room where they will eat and sleep, and they should use a separate bathroom.

It’s OK to go into the infected party’s room to drop off food, Sax advises, but both the patient and the caregiver should wear a mask, and if possible, an inexpensive plastic face shield or lab goggles to cover your eyes in addition to your nostrils and mouth — eyes are a potential entry point for the virus.

For milder cases, at-home treatment largely addresses the symptoms.

“Given that we don’t have any verified therapy that we can give people early on in the course, our main management is focused on symptomatic relief for coughs, fevers, muscle pains and the like,” says Harvard Medical School physician Dr. Abraar Karan. “Over-the-counter Tylenol for fevers and pain, or anti-cough medications are both options for people who don’t have significant medical conditions that would prevent them from taking these medications.”

Sax says it’s a good idea to go into your loved one’s room three or four times a day, say hi and see how they’re doing. It’s “completely fine” to prepare food for them; just make sure to wash the dishes and your hands afterward with soapy water. You should check temperatures twice a day and expect a higher number in the afternoon than early morning.

Another helpful tool is a pulse oximeter, which can be used to measure oxygen levels. Look for numbers in the high 90s to 100s when monitoring your loved one. A number in the low 90s is alarming, Sax and Karan say, and if those are the results you’re noticing, seek medical attention for your loved one. But you shouldn’t be falsely reassured by good numbers either, medical experts warn—and there are some noted problems with getting good readings to begin with.

Dr. James Aisenberg, a gastroenterologist and clinical professor of medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, was diagnosed with COVID-19 in March and has since recovered. For him, it was important to keep the communication flowing with his physician and keep meticulous notes on his condition and recovery progress.

“The caregiver should have a physician or a health-care contact whom they can email because it’s a bumpy and long recovery process,” Aisenberg says. “It’s very helpful to have someone to reach out to for reassurance and counsel who knows the natural history of the coronavirus infection, who can say ‘That’s a red flag, come to the hospital’.”

Sax says that at home, there are some clear things to watch out for when it comes to symptoms: if your loved one has a harder time breathing, if fever is spiking (especially in older people), if there’s delirium or signs of dehydration like fatigue, dizziness or overly-yellow urine.

Because the recovery process is slow, taxing and done in isolation, Aisenberg says it was important for him to find nourishing moments of human connection with family between the stretches of alone time.

“You want to be together in a moment where you cannot touch each other; to be close at a moment where you can’t physically be close,” he notes. “Because both parties — the patient and the family — need that closeness. So the most important thing for a caregiver is to be “attentive, supportive and present—but observe social distancing (at least 6 feet even with a mask on) and hygiene.”

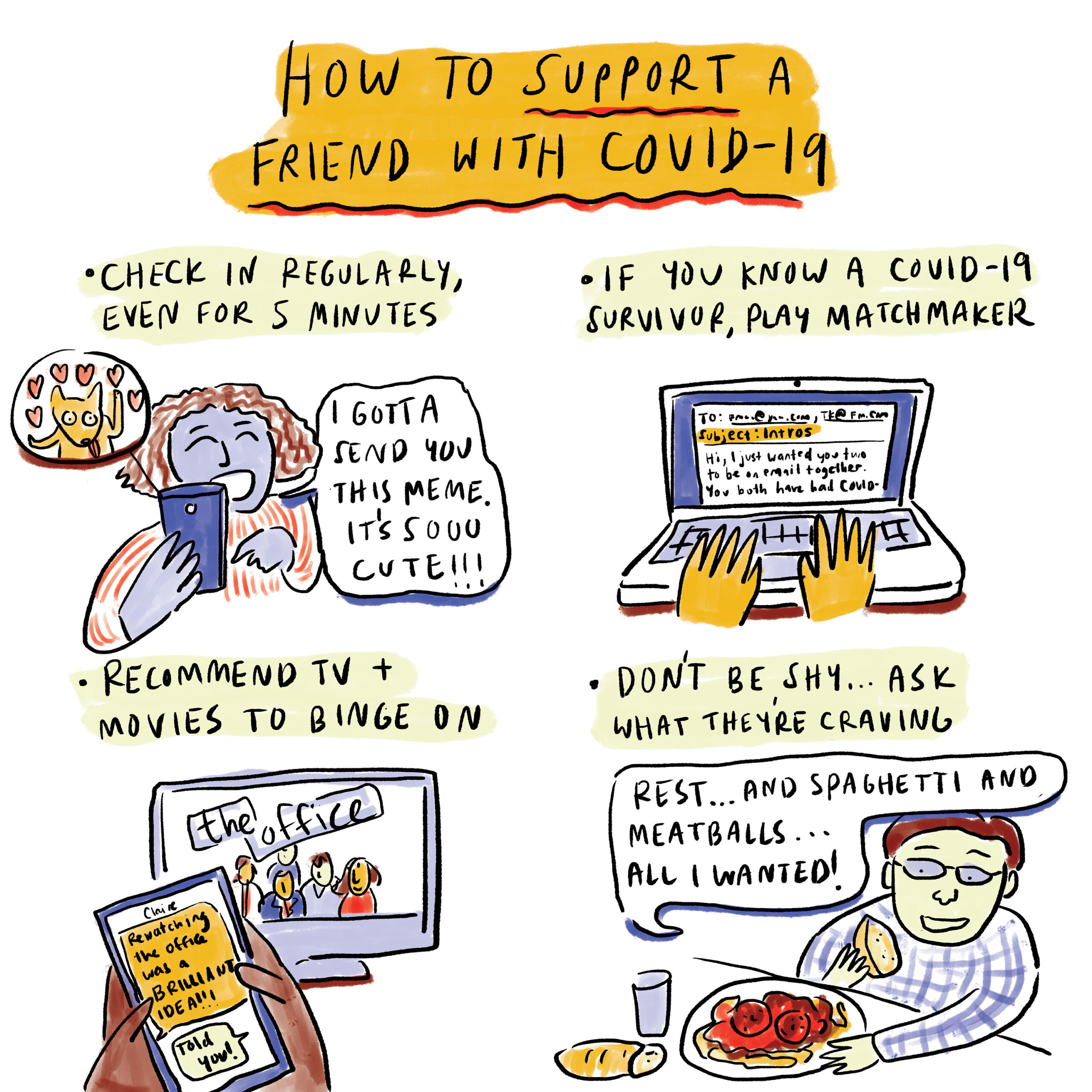

Though it may be hard to physically connect while you have the virus, our sources who’d coped with COVID-19 found moments of joy in video chats, phone calls and other expressions of love and care, from cards to homemade soup to gifts of food and flowers.

Dr. Jasmine Eugenio, a pediatrician in Los Angeles, California, who recovered from COVID-19, says she was brought to tears when people drove past her bedroom window to wave hello. And when she got a mango, it was an epiphany!

“I lost my sense of taste until Day 6 when I asked for a mango and the taste exploded in my mouth,” Eugenio says. That led her to fresh fruit and popsicles.

Dr. Madhuri Reddy, a geriatrician at Harvard Medical School and Hebrew SeniorLife, stresses it’s important for caregivers to take care of themselves too,

“Be easy on yourself,” says Reddy. “This is a difficult time for everybody — and caretakers provide such an immense service.”

Pranav Baskar is a freelance journalist and U.S. national born in Mumbai.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))