Larry Pichon called an ambulance to take his wife, Judy, to a hospital in Lake Charles, in southwest Louisiana, on the morning of July 13. He’d had to do this before.

She had a rare autoimmune disease — granulomatosis with polyangiitis, which causes inflammation of blood vessels and can be particularly damaging for the lungs and kidneys. It wasn’t uncommon for Judy to make a trip to the emergency room.

“When she got in the ambulance to go was the last time I saw her, and that was around nine o’clock,” Larry remembered.

Larry would normally have accompanied his wife and waited at the hospital, but rules enacted amid the surge of coronavirus cases meant he couldn’t stay. Judy called around 5 p.m. to say she was feeling better. She told him not to come to the hospital. At 8 p.m., her condition changed. Judy was put on a ventilator.

“Normally you go on a ventilator, you go in the ICU — there were no beds in the ICU due to the coronavirus,” he said.

Hospital staff said he could see her if he could get there in time.

But, “when I got there, she had already, had just died.”

Judy didn’t test positive for the coronavirus. Instead, Larry said, her heart stopped. If it weren’t for the pandemic, Larry believes his wife would be alive. He believes she would have been given more attentive care if she’d been transferred to the ICU, possibly saving her life. But even if not, the pandemic meant she died alone. He never got the chance to say goodbye.

“Because of corona, she was basically, in my opinion, taken away from me,” he said. “It happened because somebody else did not take the precautions that they should have taken, got the virus, and then had that bed that my wife needed.”

Officials with the CHRISTUS Ochsner St. Patrick Hospital would not comment on Judy Pichon’s case and whether her death was related to crowding, but it is one of several hospitals in Lake Charles facing a severe shortage in beds. In a statement, Dr. Timothy Haman, the chief medical officer of the hospital, said the hospital’s emergency department nurses are trained in critical care and “while it definitely isn’t ideal to hold patients in the ED for a prolonged amount of time, it is unfortunately a common phenomenon across the country right now.”

As the coronavirus has moved from coastal cities to more rural areas of the country, disparities in hospital capacity are causing problems for those not equipped to deal with the recent surge of the pandemic.

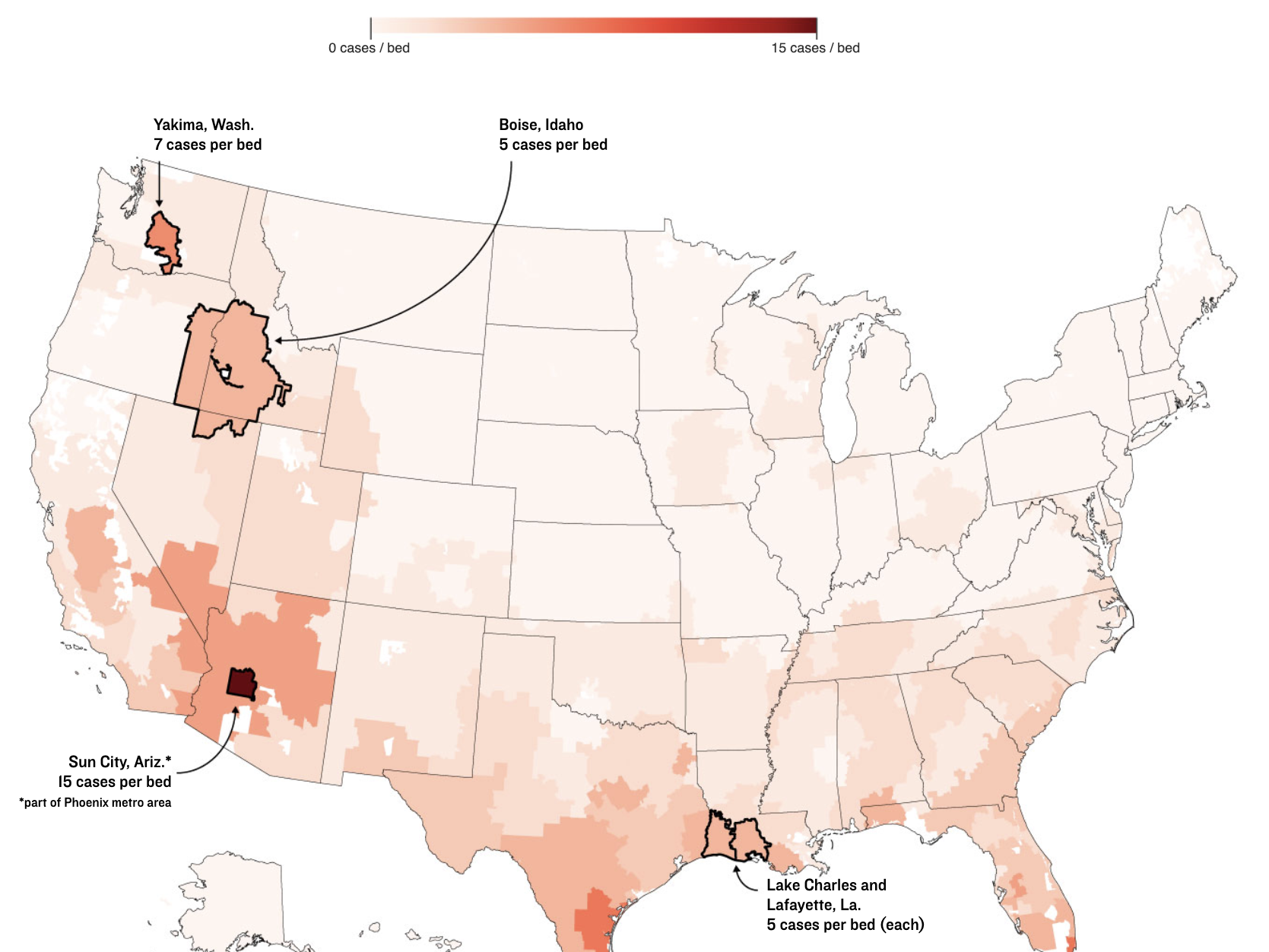

An NPR analysis of new COVID-19 cases and hospital capacity shows that in addition to well-known hot spots like Arizona, Texas and Florida, there’s cause for concern in other parts of the country, too. Places like southwest Louisiana, eastern Washington state and Boise, Idaho, have had to shuffle patients between hospitals in order to ensure everyone can get a bed.

The NPR analysis looked at new cases in hospital referral regions, which are areas of the country where patients are likely to be referred when they’re trying to get care. Because coronavirus case counts are generally available at only the county level — and since hospital capacity can fluctuate — NPR’s figures are estimates for how many cases a hospital referral region has.

Southwest Louisiana: Staff Shortages

Lake Charles is among two regions in Louisiana where the renewed wave of the pandemic may overwhelm hospital capacity. It sits at the edge of the Gulf of Mexico and the border with Texas. For weeks, Lake Charles and another hospital referral region, Lafayette, have had the state’s highest rates of new coronavirus cases and its greatest growth in hospitalizations. According to state data, there are just 20 intensive care unit beds left in the Lake Charles region as of Sunday. Lafayette, a few hours west of New Orleans in the heart of Acadiana, has just 26. In both, the major hospitals are either near capacity or already full.

The governor has requested extra ICU nurses, doctors and respiratory therapists through the Federal Emergency Management Agency, but the request is pending. Hospitals have been tapping contract nurses, but “that is drying up pretty quick,” said Dr. Manley Jordan, the chief medical officer of Lake Charles Memorial Hospital.

“Everybody has their limits. Everybody has a breaking point,” Jordan said. “What keeps me up at night is not having any light at the end of the tunnel.”

Some hospitals are so full that they’re on what’s called “diversion” — meaning that they restrict which patients they take from surrounding areas or other facilities, sending some patients farther away to get care. In those hospitals, the only way in is through the emergency room.

Lafayette General Health, a Level II trauma center, has been on complete diversion for over a week, even for patients from smaller local facilities within its own network. Chief Medical Officer Amanda Logue said she doesn’t think the community understands that a hospital swamped with coronavirus patients has an impact on other health care, too.

“It’s all the other things that them and their family need. And we’ve had to turn them all away,” she said. “So if you’re in a car accident, I’m sorry, but we can’t take you at this time.”

Boise: Walking A Fine Line

Idaho saw 3,228 confirmed coronavirus cases in the past week, and about two-thirds of those were in the greater Boise area. More than 200 people statewide were hospitalized with confirmed or suspected cases of COVID-19 as of this past weekend. Almost 20% of Idaho’s COVID-19 deaths over the course of the pandemic happened in the past week.

Two intensive care units at St. Luke’s Health System hospitals filled up last week. They began sending patients to the main facility in Boise. The intensive care unit there was running at about 130% of normal capacity. Respiratory therapists are being sent from St. Luke’s hospital two hours away to help.

The outbreak has left Idaho’s major hospitals walking a fine line. They want people in the community to take the virus seriously, but they’re also careful to say they aren’t full — they can still care for all their patients.

“We are taking care of everyone who needs care today, and we will continue to do that,” Chris Roth, the president and CEO of St. Luke’s Health System, Idaho’s largest health care system, said during a press conference with local medical leaders earlier this month. “But August will be too late, and we will find ourselves in a situation where that could very well change.”

Yakima, Wash.: Workarounds

In mid-June, Yakima in eastern Washington emerged as the epicenter of the state’s outbreak, with the highest rate of infections of any West Coast county. The NPR analysis shows Yakima has one of the worst ratios of hospital beds to people with coronavirus infections in the country.

The community of about 250,000 hadn’t seen a crush of patients in early spring like nearby Seattle. But the virus was picking up speed, sweeping through long-term care facilities, sickening farmworkers and spreading uncontrollably.

One of those to fall ill was Leola Reeves’ 70-year-old stepfather, who was hospitalized for two weeks with COVID-19. “My mom got the phone call. What are his final wishes? And that was extremely hard,” said Reeves, 37.

On the side of a busy roadway, Reeves has helped set up more than 8,000 red flags, each with a black silhouette, to represent the number of confirmed coronavirus cases in her hometown.

Yakima’s health care system was particularly vulnerable to that surge of patients. In January a major hospital closed, leaving only one other hospital in the city with just 11 critical care beds.

At one point, Dr. Tanny Davenport with Virginia Mason Memorial hospital in Yakima said 17 patients were transferred out of the county in a single day. “We’ve never had anything close to that number ever in our history,” Davenport said.

Leola Reeves began to worry her stepfather might be transferred hours away to Seattle. “Luckily, that did not happen. And they were able to care for him here.”

One reason he didn’t have to be transferred is because of the way the hospital adapted during the crisis.

Virginia Mason Memorial doubled its critical care beds and retrofitted floors to care for patients. Davenport said the biggest challenge wasn’t just physical space. “We had beds, but what we didn’t have was team members to safely take care of those patients,” he said.

The health care system was still on the brink. Then a combination of good fortune and community action led to a remarkable turnaround. While Yakima was inundated, other parts of Washington got the virus under control, so there was always somewhere to transfer patients.

“That was really our saving grace,” Davenport said.

Meanwhile, local health officials, working with the hospital, businesses and community groups, launched a massive face mask awareness campaign. A survey from Memorial Day weekend showed only 35% of people in Yakima were wearing face masks.

“Having that data point actually was really helpful,” said Lilian Bravo with the Yakima Health District. Bravo said they blanketed the community with free masks and shifted their messaging to focus on the goal of improving that number so Yakima could reopen.

“That was a key turning point,” Bravo said. “Having that tangible goal ended up being very, very effective.”

A month later, the same survey showed 95% of people were wearing face masks, and the results became even more clear as hospitalizations and cases continue to fall.

“Masking is what has changed,” Davenport said. “For us to go from 200 cases a day to 100 cases a day in six weeks is incredible.”

Nationwide: What’s Next?

Whether hospitals and communities can continue to keep ahead of rising caseloads is the challenge and the question.

Dr. Ashish Jha, the director of Harvard Global Health Institute, originally compiled hospital capacity data used in NPR’s analysis in March to estimate when hospitals might fill up. At that time, health leaders were worried about a single crushing incident of coronavirus infections that would overwhelm U.S. hospitals. Now, he says, he’s concerned about something else, too.

“It may come differently as opposed to a single massive surge that overwhelms hospitals. What we might get is just this constant flow of critically ill patients that are just barely what a hospital can manage,” Jha says.

“Once you get out of those major academic centers and start getting into community hospitals and regional hospitals, they don’t have those deep benches. They don’t have the wealth of resources that they can tap into. So I am very worried that in the days and weeks ahead, if these hospitals continue to function at or above capacity, they’re going to have a very hard time keeping going.”

Additional reporting by Huo Jingnan.

Copyright 2020 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))