A fight is looming over whether to develop a mostly empty lot on the west side of Atlanta or turn it into a memorial to a grim chapter in the city’s past. It’s the site of the old Chattahoochee Brick Co., located in a sort-of horseshoe formed by a rail line, the Perimeter and the Chattahoochee River.

The place seems innocent enough now. Near the entrance, there’s a sunny, exposed cement lot, overgrown with weeds. Piles of bricks are scattered around, left over from a modern brick company. In the woods behind that lot are remnants of an earlier factory, the Chattahoochee Brick Co., which operated in Atlanta at the turn of the 20th century.

‘A Place of Absolute Horror’

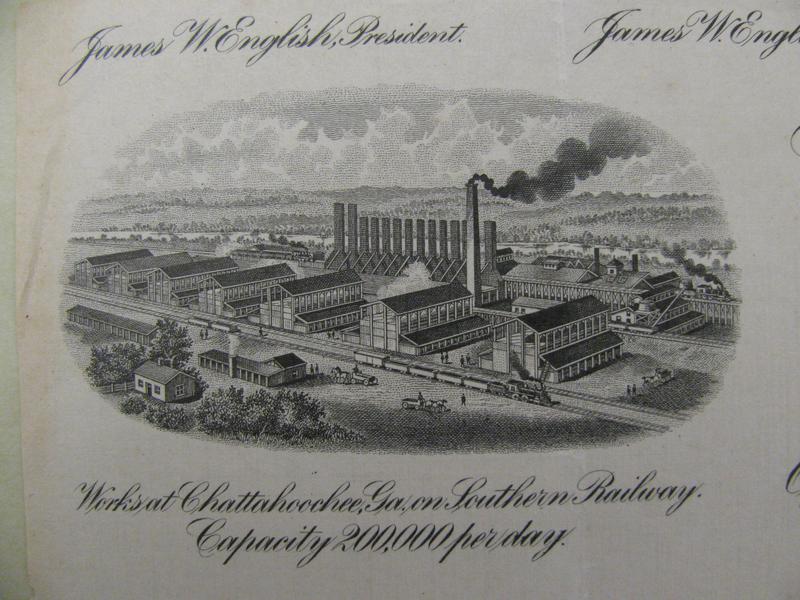

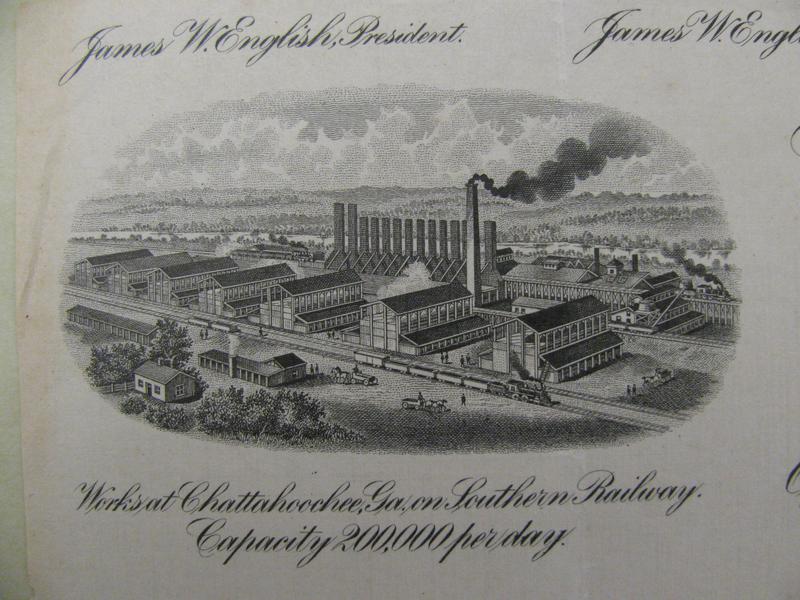

The Chattahoochee Brick Co. churned out hundreds of thousands of bricks a day. It was owned by Civil War hero and then-mayor of Atlanta Capt. James English, and it has an ugly story.

“Chattahoochee Brick was a place of absolute horror,” said Douglas Blackmon, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book, “Slavery by Another Name.” The book, and a Public Broadcasting Service documentary based on it, is about the practice of using convict labor in mines, on farms and in factories, like Chattahoochee Brick, in the South after the Civil War. Most of the convicts were black. Many were arrested for petty crimes, like vagrancy.

“These were places of incredibly high mortality rates,” said Blackmon. “Starvation, maltreatment, constant torture to exact more labor out of the men and handful of women who were forced to work in these places.”

In his book, Blackmon describes scenes at the Chattahoochee Brick Co. of men being left to die after severe beatings. There are no graves visibly marked, but he and others said it’s likely that people are buried there.

“There’s an overwhelming body of evidence, said Blackmon, “that this was essentially a death camp.”

Site for Sale

There are still traces of the old Chattahoochee Brick Co. factory back in the woods: rusted metal, hunks of cement, trails of broken-up pieces of bricks. The buildings that made up the modern brick factory were torn down in 2011.

Now the property is for sale. The lot is zoned for heavy industrial use. It’s right on a major rail line and across the street from a petroleum terminal.

The conservation organization Trust for Public Land looked into buying the land several years ago and had the site under contract, but the owner of the property broke off the deal after the group asked for more environmental studies.

Now, a South Carolina energy company is moving to buy it to build a biofuel shipping facility on the land.

That company, Lincoln Energy Solutions, didn’t return requests for an interview. Neither did the real estate broker. The current owner of the site is a company called General Shale. A spokeswoman there said because of a nondisclosure agreement, they can’t discuss it.

‘A Further Slap in the Face’

“I can understand why they got into this,” said Bob Kent, who lives near the property. Kent said he can see how the energy shipping facility would seem like a good plan to a company unfamiliar with the site’s past. But he said given that history – and the proximity to the Chattahoochee River – the plan to build an industrial facility is wrong.

“This is something we feel needs to be stopped,” he said.

Kent is working with other people who live near the property to bring more attention to the place’s history and its possible future. Donna Stephens, another neighbor, said she’s lived her whole life in Atlanta, but never learned in school about this piece of the city’s story.

“For it to be right under our feet right now is just unspeakable,” she said. “And the fact that there may be bodies buried on this land, is just a further slap in the face to those men and women and their families.”

Stephens is a board member of the nonprofit Groundwork Atlanta, which is advocating for a memorial and a park to go there.

Proctor Creek Connection

“We really need green space,” said Stephens. “There is too much cement in Atlanta, period. And for whatever reason, the west side of Atlanta just became the industrial hub.”

The city is putting more energy into adding more green space to that side of Atlanta now, though. South of the site, the BeltLine’s Westside Trail is under construction. Work has begun on Bellwood Quarry, a reservoir situated in what will eventually be an enormous park. Efforts are ramping up to clean up Proctor Creek, a perennially polluted and problematic waterway that flows from downtown to the site of the old brick factory, where it empties into the Chattahoochee River. An eventual trail along the creek, said Kent, could converge at the brick factory site with the Silver Comet Trail.

“This is the last big piece of land adjoining the river at the confluence of Proctor Creek and the Chattahoochee,” said Kent. “It should be developed. But we’d like to see some tax-paying commercial development, some recreation, a memorial here and, above all, nothing that damages the creek and the river.”

Atlanta’s Response

Officials with the city agree with Stephens and Kent. Atlanta City Councilman C.T. Martin said he imagines the site of the Chattahoochee Brick factory could become a more visible piece of Atlanta’s story.

“Let it be a history that our social studies teachers can take our kids on a tour,” he said.

Author Blackmon said as far as he knows, there is no memorial in the country to the people who died or suffered during the era of convict leasing.

“What happened at that place should be remembered,” he said. “And there is still an opportunity to remember it because unlike so many other places, unlike so much of the history of Atlanta, it has not yet been paved over.”

The real estate sale has not yet gone through. Groundwork Atlanta hopes that the city might be able to step in and buy it. The mayor’s office said it’s exploring its options for the old site.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))