In the 1960s, the U.S. was embroiled in a tense space race with the Soviet Union — and was losing. By the start of the decade, the Soviets had already sent the first satellite and the first man into space. So, on May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy made a pledge to the nation: The U.S. would land a man on the moon before the decade ended.

This challenge excited most Americans, but many Black people resented money being poured into the space race that could have gone to aid the cause of civil rights and help impoverished Black communities. At the same time, the Soviets were pointing to the racial inequality in the U.S. to show the superiority of the Communist system.

In an attempt to counter the Soviets and to increase support for the space race among Black Americans, some began urging the administration to send a Black person to space. Edward R. Murrow, then Director of the U.S. Information Agency wrote a memo to the White House saying, “Why don’t we put the first non-white man in space?”

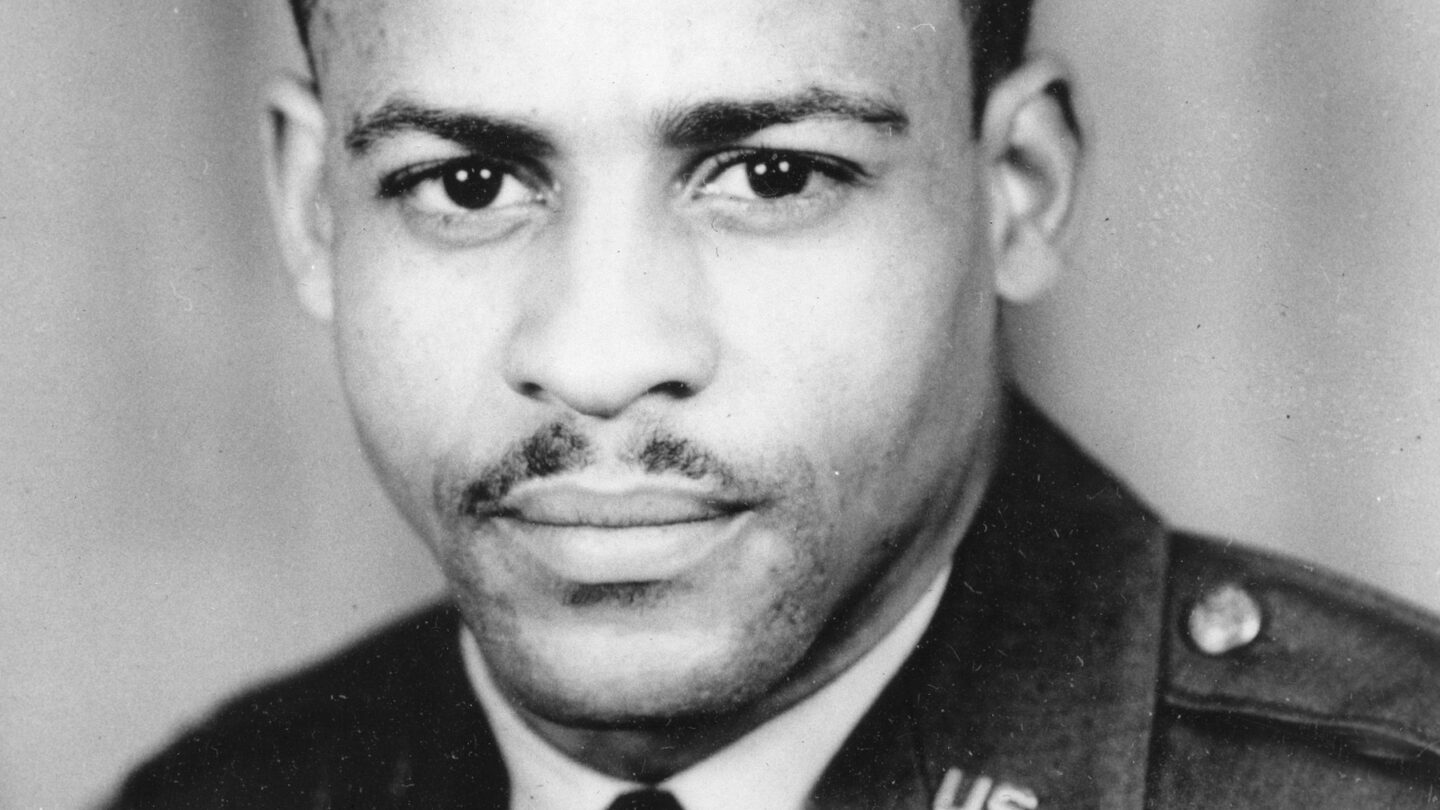

Edward J. Dwight, Jr. was a 27-year-old Air Force Captain at the time. Originally from Kansas City, he loved flying from a young age — so much so that he’d go on walks to the local airport with his mother every day.

“I was the only Black officer pilot just about every base I was stationed,” Dwight recalled. And although being only 5 foot four, “I got award after award and I was just happy as could be. I couldn’t have had a better life.”

On November 4, 1961, he got a letter inviting him to join the astronaut training program. Unsure of what to do, he relied on his mother for advice.

“She was telling me some things about how the race could be uplifted by example and inspiration,” Dwight recalled. “My mother was never wrong, so I just went for it.”

Dwight accepted the invitation, and was sent to the Aerospace Research Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base in California to begin training. The most successful trainees would be chosen to become astronauts.

“I had never faced competition like that,” Dwight said of the training. Students would be put through grueling tests so instructors could study their physical and mental limits. “They’d blow your eardrums out to see how long it would take you to recover,” Dwight recalled. “Those are the kinds of fascinating things they did to your body to see how far they could stretch it before it kind of broke.”

While he was in training, Dwight received an onslaught of attention from Black magazines.

“The first classes of astronauts were white male astronauts,” said Laurens Grant, director of the documentary Black in Space: Breaking the Color Barrier. “The fact that possibly a Black man could be involved in this was so exciting and galvanizing, particularly for the Black community.”

Dwight’s astronaut candidacy became cover news on Black magazines such as Jet, Ebony and Sepia. Dwight also began having to make press appearances. “I would leave the base and make speeches to little kids that were around six years old,” Dwight recalled. “And I thought, ‘This is really, really cool!'”

Back at Edwards, however, Dwight says, “The instructors, the classmates, everybody at Edwards Air Force Base, were livid!” He recalls the thinking at the time was, “We’re working our butts off so many days a week and this clown is going and giving speeches!”

Chuck Yeager was commander of the program at Edwards. Yeager was already an icon, esteemed for breaking the sound barrier in 1947. As commander, his word had influence on who would be selected as an astronaut. According to Dwight, Yeager was the least fond of his popularity in the press.

“Chuck Yeager hated the whole idea of me making a speech to anybody,” Dwight recalled. He said that Yeager would bring him in for tense meetings, trying to discourage him from finishing the training program.

Dwight also believes that Yeager was not fond of him from the beginning of his time in the training program. “I didn’t learn about this ’til later,” Dwight recalled. “Yeager called the students in, and these are my fellow students, and then said, ‘You have to isolate him. Don’t drink with him. Don’t invite him to your parties.’ The whole idea was to show these white students that we got to discourage him.”

The person who told Dwight about Yeager’s attempts to isolate him from the rest of his class has died. Yeager died in 2020, but wrote about Dwight in his autobiography. Addressing their relationship, Yeager wrote: “Ed Dwight was an average pilot with an average academic background. He wasn’t a bad pilot, but he wasn’t exceptionally talented either. Flying with a good bunch in a squadron, he would probably get by. But he just couldn’t compete in the space course against the best of the crop of experienced military test pilots.”

No astronauts or fellow trainees have verified Dwight’s account of Yeager’s treatment, although at least one friend, Woodson Fountain, a Black engineer who was at the base, remembers Dwight telling him about Yeager’s treatment at the time.

Whether it was racism or Yeager’s disdain of having to train someone under pressure from the Kennedy Administration, Grant said, “It just seemed like a completely complicated and fraught relationship between Chuck Yeager and Captain Ed Dwight.”

The 14 selected astronauts, titled Astronaut Group 3, were announced on October 18, 1963. Ed Dwight was not on the list. Two of the selected, Buzz Aldrin and Michael Collins were among the crew of Apollo 11 in 1969, the first moon landing.

“NASA doesn’t really have to explain who they select to become astronauts,” Grant said. “So his whole candidacy is shrouded in some mystery.”

Three years after his rejection, Dwight resigned from the Air Force. “I just erased that board,” Dwight said. “I drove off that base and I pointed my car north to Denver and I couldn’t look back.”

Though Dwight never went to space, his candidacy has earned him increased respect in the space world. In 2020, the Air Force named Dwight an honorary member of the U.S. Space Force, and in 2021, NASA named an asteroid after him.

“I’m all over it,” Dwight responded when asked if he still keeps up with all things space-related. As for his career, however, Dwight has since pivoted to the arts. He specializes in sculpting little-known Black historical figures — sort of like himself.

One of his sculptures, “Pioneer Woman,” was sent to space on the vessel Orion as part of a test mission — sending artistic works into space as proof of the creativity that will come to space, once all humans are allowed to go.

This story was produced by Mycah Hazel of Radio Diaries. It was edited by Joe Richman, Deborah George, and Ben Shapiro. You can find a longer version of this story, and other stories like it, on the Radio Diaries Podcast.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))

9(MDAxODM0MDY4MDEyMTY4NDA3MzI3YjkzMw004))