Adalei Stevens

|

Georgia Recorder

March 18th, 2024

Thousands gather each year in Georgia and nationwide during the last 10 days of January to conduct the annual homelessness census that guides legislative, funding and support efforts. The Point-in-Time headcount is the most comprehensive census for sheltered and unsheltered individuals.

Last year’s report revealed a 12% increase in the national homeless population from 2022, making it the largest population since the first count in 2007 at just over 653,000 unhoused individuals. Despite a national record high, Georgia’s 2023 headcount report shows that homelessness is down 37% since 2007.

Last March, Gov. Brian Kemp signed Senate Bill 62 into effect, which requires cities and counties to enforce public camping bans and to audit local spending on homelessness.

The audit revealed that a statewide council may be necessary to provide a coordinated response to the 4.4% growth in Georgia’s homeless population from 2020. After an estimated $549 million in federal funding was spent in Georgia between 2018-2022. If implemented, Georgia would join 33 other states and Washington, D.C. The Georgia Department of Community Affairs currently acts as the state’s housing agency but mainly administers federal and state funding, including strategy development and targeting best intervention practices.

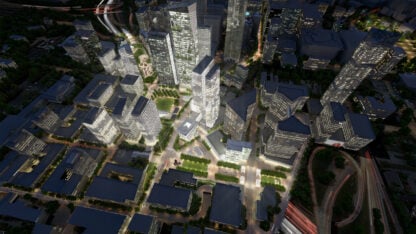

Kemp announced $9 million for new housing and necessary infrastructure across four communities as part of the Rural Workforce Housing Initiative. The Development Authority of Donalsonville and Seminole County and the cities of Alma and Vidalia each received an estimated $2.5 million, while $1.5 million was awarded to the Dalton-Whitfield County Joint Development Authority. The project is expected to produce 400 additional housing units.

Efforts to coordinate a cohesive response to homelessness emerged out of Macon as part of its initiative to end homelessness through the United Way of Central Georgia. Executive Director Jake Hall said the recently developed smartphone app, Show the Way, will act as a “decentralized case management tool” as users are prompted to ask person-centered questions regarding health and accessibility to services.

“The only way that we can address [homelessness is] if we have proper local data,” Hall said. “And that we’re working to deploy federal funding at the local level, in ways that help move the needle.”

The app also allows first responders to pinpoint encampment locations, though it’s unclear if such information will be affected by reinforced public camping bans. Show the Way is also expected to simplify future headcounts.

Shortly before this year’s count at the end of January, the city of Atlanta and Athens-Clarke County each announced budgets of about $5 million, to fund assistance programs after the 2023 headcounts revealed a 1.3% increase in unsheltered and sheltered homeless populations in those areas. People are considered sheltered homeless if they lack access to a steady place to live at night.

Of that $5 million, Athens-Clarke County allocated $2.83 million to fund proposals from organizations for homeless supportive services, unsheltered homeless activities and construction for low-barrier shelters, which will be accepted through March 8. The proposals mark the first phase of the county’s strategic plan to reduce and prevent homelessness.

Atlanta Mayor Andre Dickens’ office confirmed two initiatives on February 22 that seek to reduce ongoing safety concerns. One will implement the statewide public camping ban as the city will clear 10 to 20 bridges where unhoused individuals seeking shelter set fires for warmth. Authorities believe these encampments are responsible for fires at Cheshire Bridge Road, totaling two multi-week road shutdowns in the last two years. The other initiative will enact the Atlanta City Council’s plan to limit access to Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport as unhoused people seek shelter in the airport’s atrium.

The mayor’s office said Wellstar Atlanta Medical Center in Midtown Atlanta will be a temporary emergency shelter for at least 180 days. Similar initiatives in the past have failed to provide an alternative to cleared encampments, which creates a bigger problem, according to Hall.

“Some communities don’t admit that they have a problem serving people who are housing insecure, or they don’t want to deeply invest in homelessness services, sometimes out of fear that it will have a magnetic effect or draw people to those services,” Hall said. “And I think all of those are misguided responses to the human needs in our midst.”

This story was provided by WABE content partner Georgia Recorder.