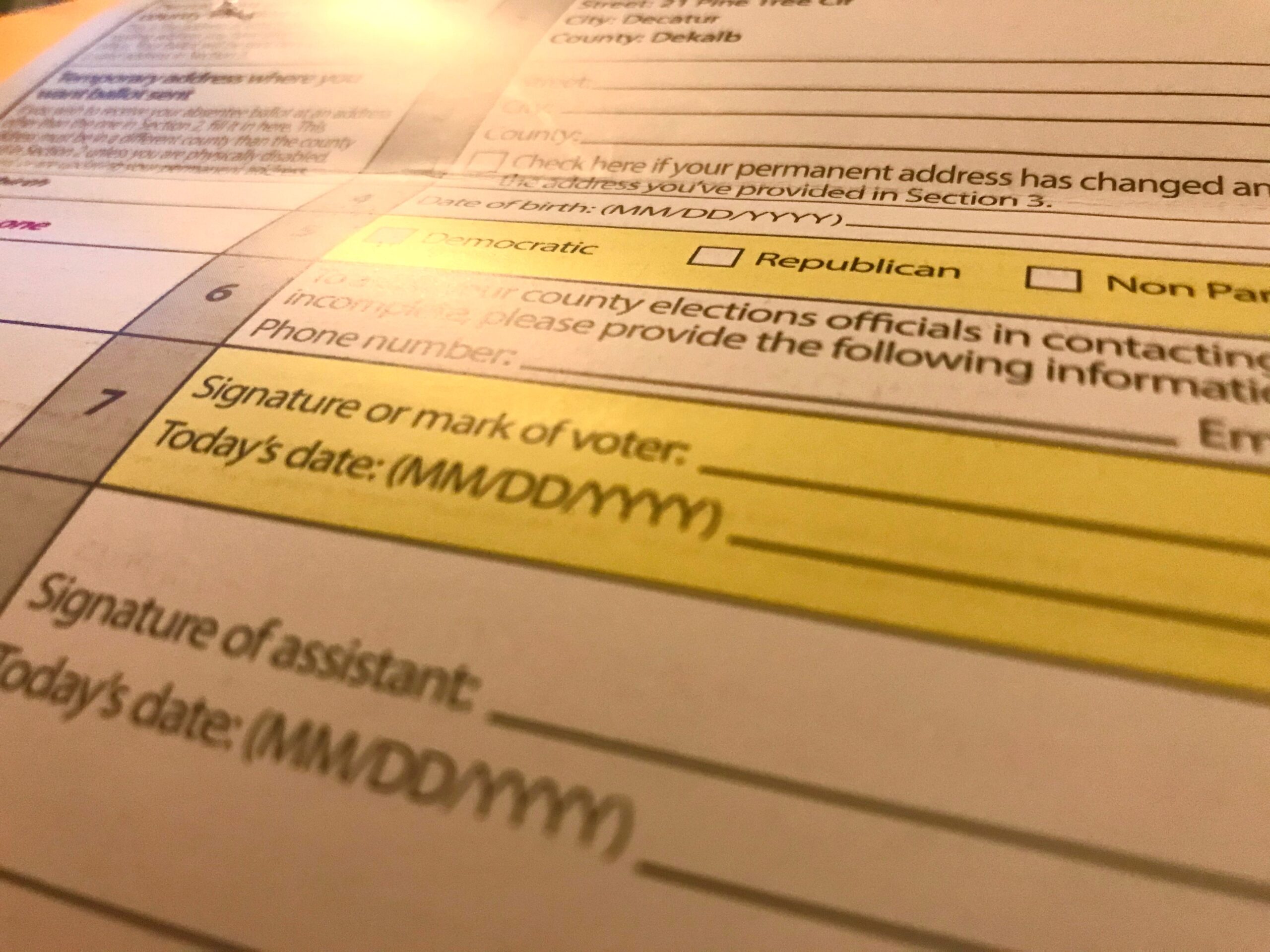

Lisa Maldonado, a flight attendant from Peachtree City, has never voted by mail. But when she got an absentee ballot application in the mail last month, she filled it out, signed it and sent it in.

Then, she got a voicemail from the Fayette County Elections office.

“So I called back and was told that there were too many vowels in my signature compared to my signature in the past,” said Maldonado. “And I said, ‘well, look at my name, it has a lot of vowels in it.’”

Under a Georgia law passed last year, such an application can no longer be rejected; instead voters have to be notified if their signature doesn’t match with the one on their voter registration.

The Fayette County Elections office says when this happens, they contact that person – as they did here – and send a verification form.

Maldonado says having to fill out another piece of paper is frustrating.

“Well, this would deter other people, they’d say ‘okay, forget it at this point, I don’t want even want to vote,’ so I was very discouraged with it,” she said.

Georgia’s primary elections will be held in June, even amid the coronavirus pandemic. As of Tuesday, nearly 900,000 of the state’s voters have requested absentee ballots. Traditionally, only 5% of Georgia voters cast ballots by mail, but that percentage is likely to rise significantly for this year’s primaries.

And that means county elections officials will spend much more time this spring examining handwriting. So how closely are counties examining how people sign their names?

“Most of the time for local officials, it’s just looking to see: does this look like the same person or not? And most election officials are not rejecting signatures if they’re close,” said Bryan Tyson, an attorney in Atlanta who has represented the state in election and voting matters.

Proponents say this signature verification provides a safeguard against abuse.

Critics say the process is flawed as handwriting can change over time. What’s more, many Georgians register to vote when they get their drivers’ license, a process that involves signing a digital pad.

“And then they tell you to sign a paper application with your handwritten signature, and that’s what they’re comparing to your digital signature on your driver’s license?” asked Saira Draper, who heads voter protection for the Georgia Democratic Party. “What are we trying to achieve there?”

Effective or not, for county elections officials, all of this is just a first step. When voters return their actual ballot along with their voter’s oath, the next examination of signatures is required to begin again.